Equity investors and long-only portfolio managers are constantly on the lookout for ways to improve their portfolios, either by yield enhancement, or risk reduction. In the case of yield enhancement, the principal focus is on adding alpha to the portfolio through stock selection and active management, while risk reduction tends to be accomplished through diversification.

Another approach is to seek improvement by adding investments outside the chosen universe of stocks, while remaining within the scope of the investment mandate (which, for instance, may include equity-related products, but not futures or options). The advent of volatility products in the mid-2000’s offered new opportunities for risk reduction; but this benefit was typically achieved at the cost of several hundred basis points in yield. Over the last decade, however, a significant evolution has taken place in volatility strategies, such that they can now not only provide insurance for the equity portfolio, but, in addition, serve as an orthogonal source of alpha to enhance portfolio yields.

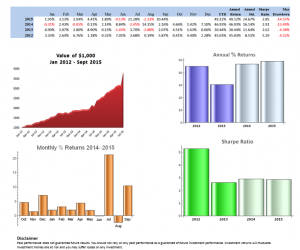

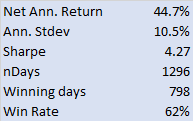

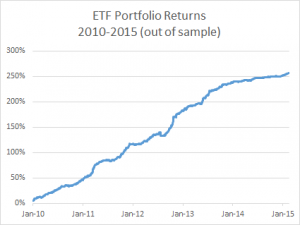

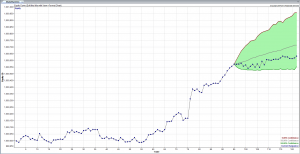

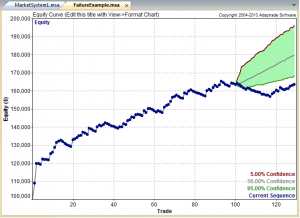

An example of one such product is our volatility strategy, a quantitative approach to trading VIX-related ETF products traded on ARCA. A summary of the performance of the strategy is given below.

The mechanics of the strategy are unlikely to be of great interest to the typical equity investor and so need not detain us here. Rather, I want to focus on how an investor can use such products to enhance their equity portfolio.

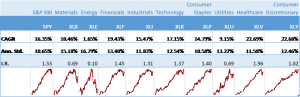

Performance of the Equity Market and Individual Sectors

The last five years have been extremely benign for the equity market, not only for the broad market, as evidenced by the performance of the SPDR S&P 500 Trust ETF (SPY), and also by almost every individual sector, with the notable exception of energy.

The risk-adjusted returns have been exceptional over this period, with information ratios reaching 1.4 or higher for several of the sectors, including Financials, Consumer Staples, Healthcare and Consumer Discretionary. If the equity investor has been in a position to diversify his portfolio as fully as the SPY ETF, it might reasonably been assumed that he has accomplished the maximum possible level of risk reduction; at the same time, no-one is going to argue with a CAGR of 16.35%. Yet, even here, portfolio improvement is possible.

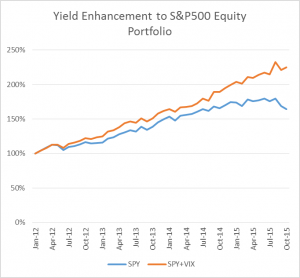

Yield Enhancement

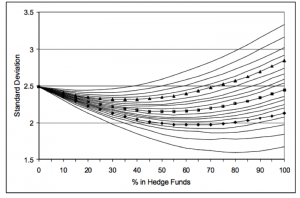

The key to improving the portfolio yield lies in the superior risk-adjusted performance of the volatility portfolio compared to the equity portfolio and also due the fact that, while the correlation between the two is significant (at 0.44), it is considerably lower than 1. Hence there is potential for generating higher rates of return on a risk-adjusted basis by combining the pair of portfolios in some proportion.

To illustrate this we assume, firstly, that the investor is comfortable with the currently level of risk in his broadly diversified equity portfolio, as measured by the annual standard deviation of returns, currently 10.65%. Holding this level of risk constant, we now introduce an overlay strategy, namely the volatility portfolio, to which we seek to allocate some proportion of the available investment capital. With this constraint it turns out that we can achieve a substantial improvement in the overall yield by reducing our holding in the equity portfolio to just over 2/3 of the current level (67.2%) and allocating 32.8% of the capital to the volatility portfolio. Over the period from 2012, the combined equity and volatility portfolio produced a CAGR of 26.83%, but with the same annual standard deviation – a yield enhancement of 10.48% annually. The portfolio Information Ratio improves from 1.53 to a 2.52, reflecting the much higher returns produced by the combined portfolio, for the same level of risk as before.

Risk Reduction

The given example may appear impressive, but it isn’t really a practical proposition. Firstly, no equity investor or portfolio manager is likely to want to allocate 1/3 of their total capital to a strategy operated by a third party, no matter how impressive the returns. Secondly, the capacity in the volatility strategy is, realistically, of the order of $100 million. A 32.8% allocation of capital from a sizeable equity portfolio would absorb a large proportion of the available capacity in the volatility ETF strategy, or even all of it.

A much more realistic approach would be to cap the allocation to the volatility component at a reasonable level – say, 5%. Then the allocation from a $100M capital budget would be $5M, well within the capacity constraints of the volatility product. In fact, operating at this capped allocation percentage, the volatility strategy provides capacity for equity portfolios of up to $2Bn in total capital.

Let’s look at an example of what can be achieved under a 5% allocation constraint. In this scenario I am going to move along the second axis of portfolio improvement – risk reduction. Here, we assume that we wish to maintain the current level of performance of the equity portfolio (CAGR 16.35%), while reducing the risk as much as possible.

A legitimate question at this stage would be to ask how it might be possible to reduce risk by introducing a new investment that has a higher annual standard deviation than the existing portfolio? The answer is simply that we move some of our existing investment into cash (or, rather, Treasury securities). In fact, by allocating the maximum allowed to the volatility portfolio (5%) and reducing our holding in the equity portfolio to 85.8% of the original level (with the remaining 9.2% in cash), we are able to create a portfolio with the same CAGR but with an annual volatility in single digits: 9.53%, a reduction in risk of 112 basis points annually. At the same time, the risk adjusted performance of the portfolio improves from 1.53 to 1.71 over the period from 2012.

Of course, the level of portfolio improvement is highly dependent on the performance characteristics of both the equity portfolio and overlay strategy, as well as the correlation between them. To take a further example, if we consider an equity portfolio mirroring the characteristics of the Materials Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLB), we can achieve a reduction of as much as 3.31% in the annual standard deviation, without any loss in expected yield, through an allocation of 5% to the volatility overlay strategy and a much higher allocation of 18% to cash.

Other Considerations

Investors and money managers being what they are, it goes against the grain to consider allocating money to a third party – after all, a professional money manager earns his living from his own investment expertise, rather than relying on others. Yet no investor can reasonably expect to achieve the same level of success in every field of investment. If you have built your reputation on your abilities as a fundamental analyst and stock picker, it is unreasonable to expect that you will be able accomplish as much in the arena of quantitative investment strategies. Secondly, by capping the allocation to an external manager at the level of 5% to 10%, your primary investment approach remains unaltered – you are maintaining the fidelity of your principal investment thesis and investment mandate. Thirdly, there is no reason why overlay strategies such as the one discussed here should not provide easy liquidity terms – after all, the underlying investments are liquid, exchange traded products. Finally, if you allocate capital in the form of a managed account you can maintain control over the allocated capital and make adjustments rapidly, as your investment needs change.

Conclusion

Quantitative strategies have a useful role to play for equity investors and portfolio managers as a means to improve existing portfolios, whether by yield enhancement, risk reduction, or a combination of the two. While the level of improvement is highly dependent on the performance characteristics of the equity portfolio and the overlay strategy, the indications are that yield enhancement, or risk reduction, of the order of hundreds of basis points may be achievable even through very modest allocations of capital.