Almost at the very moment I published a post featuring some interesting research by Glabadanidis (“Market Timing With Moving Averages” (2015), International Review of Finance, Volume 15, Number 13, Pages 387-425 – see Yes, You Can Time the Market. How it Works, And Why), several readers wrote to point out a recently published paper by Valeriy Zakamulin, (dubbed the “Moving Average Research King” by Alpha Architect, the source for our fetching cover shot) debunking Glabadanidis’s findings in no uncertain terms:

We demonstrate that “too good to be true” reported performance of the moving average strategy is due to simulating the trading with look-ahead bias. We perform the simulations without look-ahead bias and report the true performance of the moving average strategy. We find that at best the performance of the moving average strategy is only marginally better than that of the corresponding buy-and-hold strategy.

So far, no response from Glabadanidis – from which one is tempted to conclude that Zakamulin is correct.

I can’t recall the last time a paper published in a leading academic journal turned out to be so fundamentally flawed. That’s why papers are supposed to be peer reviewed. But, I guess, it can happen. Still, it’s rather alarming to think that a respected journal could accept a piece of research as shoddy as Zakamulin claims it to be.

What Glabadanidis had done, according to Zakamulin, was to use the current month closing price to compute the moving average that was used to decide whether to exit the market (or remain invested) at the start of the same month. An elementary error that introduces look-ahead bias that profoundly impacts the results.

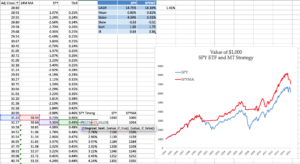

Following this revelation I hastily checked my calculations for the SPY marketing timing strategy illustrated in my blog post and, to my relief, confirmed that I had avoided the look-ahead trap that Glabadanidis has fallen into. As the reader can see from the following extract from the Excel spreadsheet I used for the calculations, the decision to assume the returns for the SPY ETF or T-Bills for the current month rests on the value of the 24 month MA computed using prices up to the end of the prior month. In other words, my own findings are sound, even if Glabadanidis’s are not, as the reader can easily check for himself.

Nonetheless, despite my relief at having avoided Glabadanidis’s blunder, the apparent refutation of his findings comes as a disappointment. And my own research on the SPY market timing strategy, while sound as far as it goes, cannot by itself rehabilitate the concept of market timing using moving averages. The reason is given in the earlier post. There is a hidden penalty involved in using the market timing strategy to synthetically replicate an Asian put option, namely the costs incurred in exiting and rebuilding the portfolio as the market declines below the moving average, or later overtakes it. In a single instance, such as the case of SPY, it might easily transpire simply by random chance that the cost of replication are far lower than the fair value of the put. But the whole point of Glabadanidis’s research was that the same was true, not only for a single ETF or stock, but for many thousands of them. Absent that critical finding, the SPY case is no more than an interesting anomaly.

Finally, one reader pointed out that the effect of combining a put option with a stock (or ETF) long position was to create synthetically a call option in the stock (ETF). He is quite correct. The key point, however, is that when the stock trades down below its moving average, the value of the long synthetic call position and the market timing portfolio are equivalent.