Too Cool for School?

Startups and Venture Capital are red hot right now. And very cool. If that isn’t a contradiction. Perusing the Business Insider list of “The 38 coolest startups in Silicon Valley”, one is struck by the sheer ingenuity of some ideas. And the total stupidity of others.

Innovation is hard. I have been doing for over 30 years in systematic trading and it never gets any easier. Ideas with great theoretical underpinnings sometimes just don’t work. Others look great in backtest, but fail to transition successfully into production. Some strategies work great for a while, then performance fades as market conditions change. What makes innovation so challenging in the arena of investment management is the competition: millions of very smart minds looking at the same data and trying to come up with something new, often using very similar approaches.

Innovation in the real world is just as challenging, but in a different way. It’s easier in the beginning – you have a whole world of possibilities to play with and so it should be less challenging to come up with something new. But innovation is much more difficult than it first appears. If your idea has any value, chances are someone has already thought of it. They may be developing it now. Or they may have tried to develop the concept and found flaws in it that you have yet to discover.

Innovation Is Hard

I have made a few attempts at innovation in the real world. The first was a product called Easypaycard, a concept that a friend of mine came up with at the start of the internet era. The idea was that you could use the card to send money to anyone, anywhere in the world, via the internet, even if they didn’t have a bank account. Aka Paypal. Couldn’t get anyone interested in that idea.

Then there was a product called Web Telemetrics: a microchip that you could place on any object (or person) and track it on an interactive online map, that would provide not only location, but also other readings like temperature, stress and, in the case of a person, heart rate, etc. Bear in mind, this was in 1999, long before Google maps and location services like Apple’s “find my phone”. I thought it was a rather ingenious concept. The VCs didn’t agree – in the final competition they allocated the money to a company selling women’s shirts online. After that I decided to call it quits, for a while.

There matters stood until 2013, when I came up with a consumer electronics product called Adflik. This contained some quite clever circuitry and machine learning algorithms to detect commercials, when it would switch to the next commercial-free station in your playlist of channels. I thought the product concept was great, but I seriously under-estimated the ad-tolerance of the average American. Only one other person agreed with me! Successful product innovation is tough.

You would think that after three total failures I would hang up my boots. It’s not as though my work in investment research is uncreative, or unrewarding. But I find the idea of developing a physical product, or even an electronic product like an iPhone app, compelling.

Venture Capital Returns

When you ask a venture capitalist about all this, he is likely to respond, rather haughtily, that his business is not about innovation, but rather to produce a return for his investors. Looking at some of the “hottest” startups, however, suggests to me that we are right back where we were in 1999. That gives me serious cause for concern about the returns that VC funds are likely to produce going forward, especially when interest rates start to rise.

For example, the business model for one of these firms is a grocery delivery service: after you have selected your very expensive groceries from Whole Foods, they will shop and deliver your order to you for an extra $3.99. Sounds like a nice idea, but a $2Bn valuation? Ludicrous. That business is going to evaporate in a puff of smoke at the first sign of a recession, or market correction, which could be right around the corner.

So how good are VC’s at producing investment returns? I did a little digging. What I found was that, while in general the VC fund industry is happy to trumpet its returns, it is almost totally silent about the other half of the investment equation: risk. As for something like a Sharpe Ratio – what that?

To answer I dug up some data from Cambridge Associates on their US Venture Capital Index, which measures quarterly pooled end-to-end net returns to Limited Partners. The index data runs from 1981 to Q2 2014, which is plentiful enough to perform a credible analysis on. Here is what I found:

- CAGR (1981-Q2 2-14) : 13.85%

- Annual SD: 20.35%

- Sharpe Ratio: 0.68

Impressive? Not at all. Any half-decent hedge fund should have a Sharpe Ratio of at least 1. Our own Volatility ETF strategy, for example, has a Sharpe of over 3. We are currently running several high frequency strategies with double-digit Sharpe Ratios.

Note that in computing the Sharpe Ratio, I have ignored the risk free rate of return, which at times during the 1980’s was in double digits. So, if anything, the actual risk adjusted performance is likely significantly lower than stated here.

VC Funds vs Hedge Funds

Why does this matter? Simple – if you gave me a risk budget equivalent to the VC Index, i.e. a standard deviation of 20% per annum, our volatility strategy would have produced a CAGR of over 60%, for the same degree of investment risk. A high frequency strategy operating at the same risk levels would produce returns north of 200% annually!

Of course, just as with hedge funds, the Cambridge Associates index is an “average” of around 1400 VC funds, some of which will have outperformed the benchmark by a significant margin. Still, the aggregate performance is not exactly stellar.

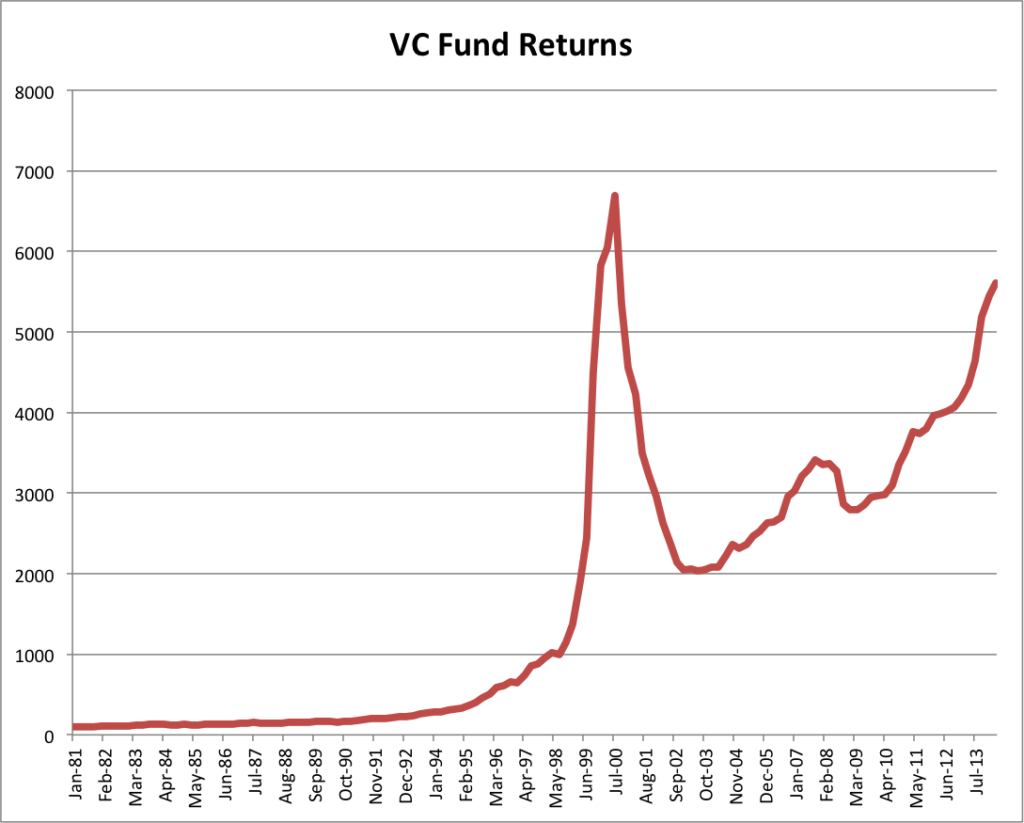

But it gets worse. Look at the chart of the compounded index returns over the period from 1981:

Source: Cambridge Associates

The key point to note is that the index has yet to regain the levels is achieved 15 years ago, before the dot com bust. If VC funds operated high water marks, as most hedge funds do, the overwhelming majority of them would gone out of business many years ago.

So Why Invest in VC Funds?

Given their unimpressive aggregate performance, why do investors invest in VC funds? One answer might lie in the relatively low correlations with other asset classes. For example, over the period from 1981, the correlation between the VC index and the S&P 500 index has averaged only 0.34.

Again, however, if low correlation to the market is the issue, investors can do better by a judicious choice of hedge fund strategy, such as equity market neutral, for example, which typically has a market correlation very close to zero.

Nor is the absolute level of returns a factor: plenty of hedge funds measure their performance in terms of absolute returns. And if investors’ appetite for return is great enough to accommodate a 20% annual volatility, there is no difficulty borrowing at very low margin rates to leverage up the return.

One rational reason for investors’ apparently insatiable appetite for VC funds is capacity: unlike many hedge funds, there is no problem finding investments capable of absorbing multiple $billions, given the global pretensions, rapid burn rates and negligible cash flows of many of these new ventures. But, of course, capacity is only an advantage when the investment itself is sound.

Plowing vast sums into grocery collection services, or online women’s-wear stores, may appear a genius idea to some. But for the rest of us, as the inestimable Lou Reed put it, “other people, they gotta work”.