High Frequency Trading Strategies

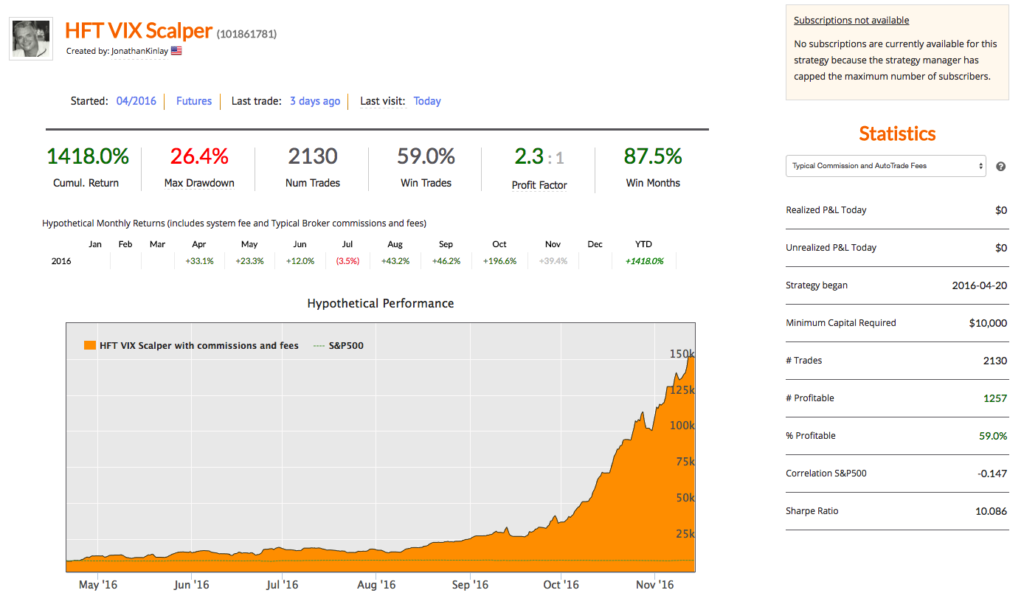

One of the benefits of high frequency trading strategies lies in their ability to produce risk-adjusted rates of return that are unmatched by anything that the hedge fund or CTA community is capable of producing. With such performance comes another attractive feature of HFT firms – their ability to make money (almost) every day. Of course, HFT firms are typically not required to manage billions of dollars, which is just as well given the limited capacity of most HFT strategies. But, then again, with a Sharpe ratio of 10, who needs outside capital? This explains why most investors have a difficult time believing the level of performance achievable in the high frequency world – they never come across such performance, because HFT firms generally have little incentive to show their results to external investors.

By and large, HFT strategies remain the province of proprietary trading firms that can afford to make an investment in low-latency trading infrastructure that far exceeds what is typically required for a regular trading or investment management firm. However, while the highest levels of investment performance lie beyond the reach of most investors and money managers, it is still possible to replicate some of the desirable characteristics of high frequency strategies.

Quantitative Equity Strategy

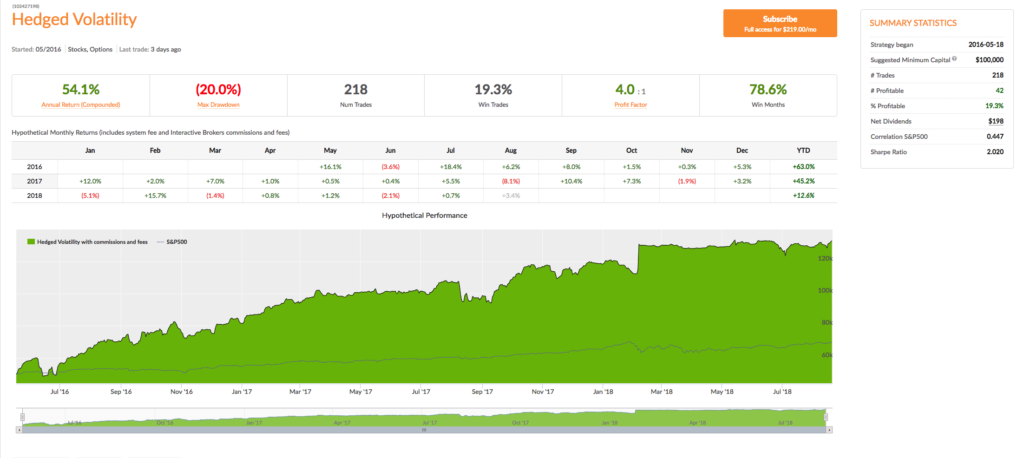

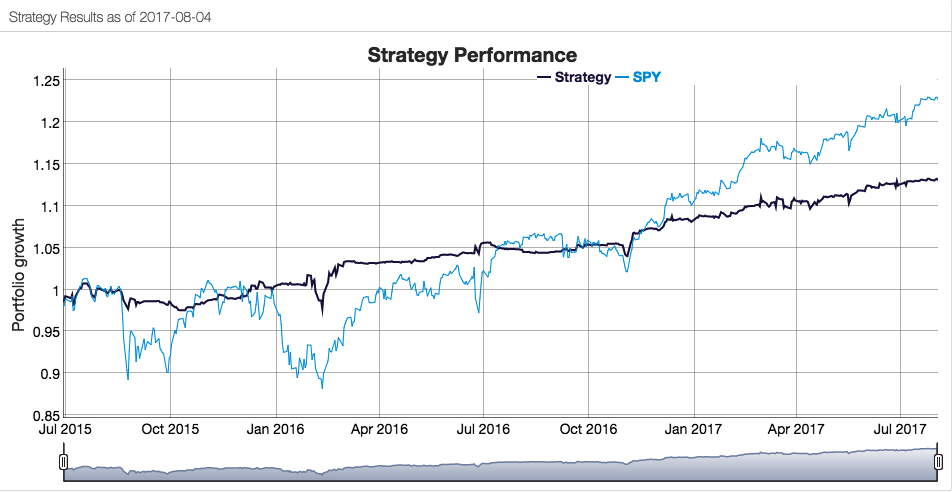

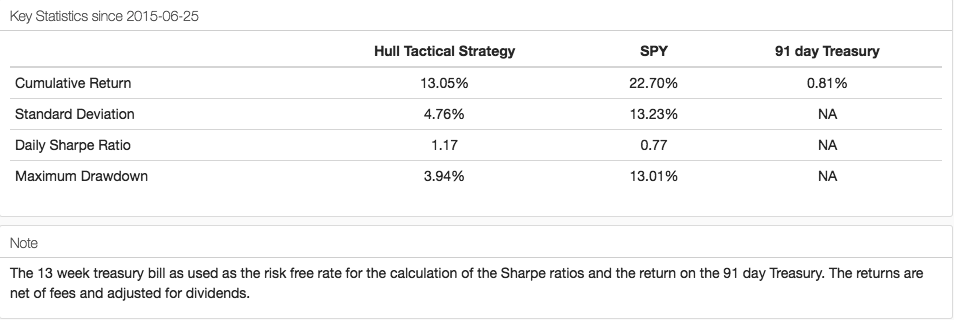

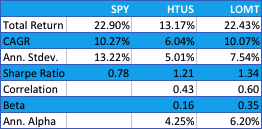

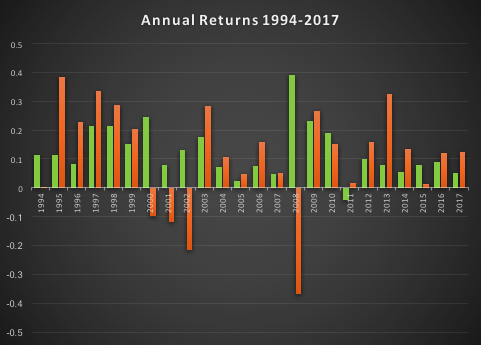

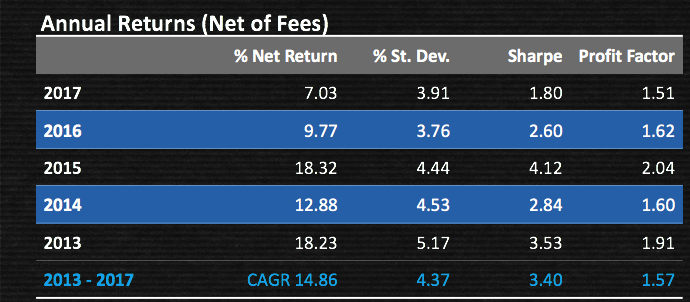

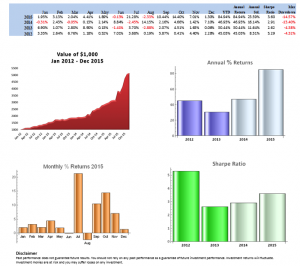

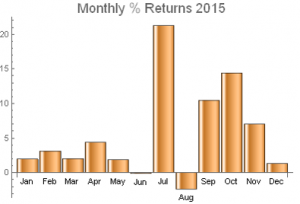

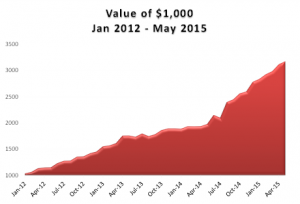

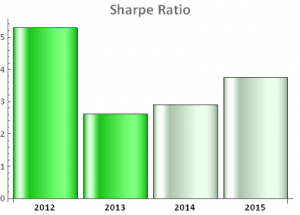

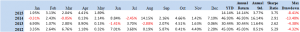

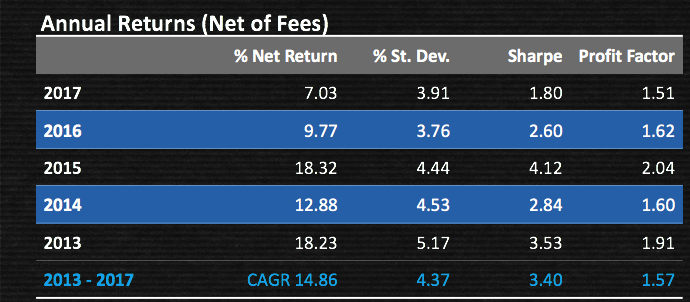

I am going to use an example our Quantitative Equity strategy, which forms part of the Systematic Strategies hedge fund. The tables and charts below give a broad impression of the performance characteristics of the strategy, which include a CAGR of 14.85% (net of fees) since live trading began in 2013.

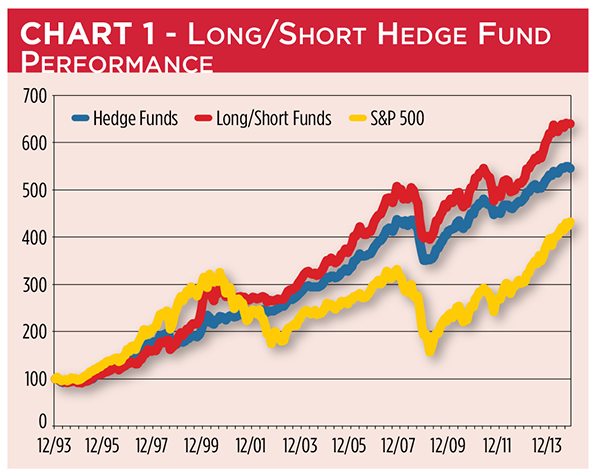

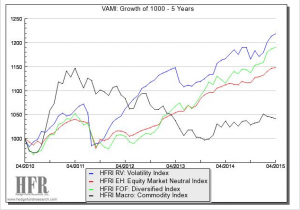

This is a strategy that is designed to produce returns on a par with the S&P 500 index, but with considerably lower risk: at just over 4%, the annual volatility of the strategy is only around 1/3 that of the index, while the maximum drawdown has been a little over 2% since inception. This level of portfolio risk is much lower than can typically be achieved in an equity long/short strategy (equity market neutral is another story, of course). Furthermore, the realized information ratio of 3.4 is in the upper 1%-tile of risk-adjusted performance amongst equity long/short strategies. So something rather more interesting must be going on that is very different from the typical approach to long/short equity.

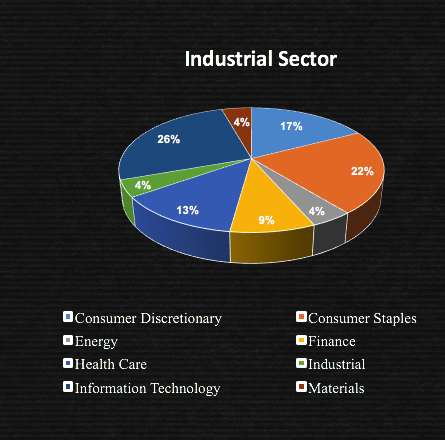

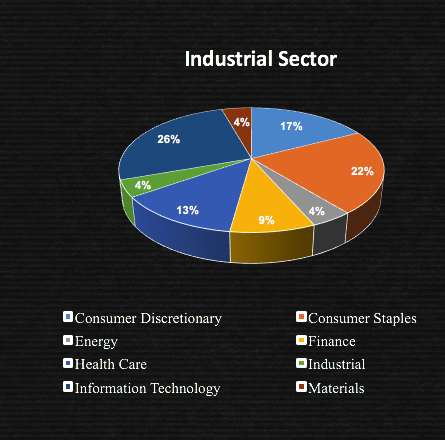

One plausible explanation is that the strategy is exploiting some minor market anomaly that works fine for small amounts of capital, but which cannot be scaled. But this is not the case here: the investment universe comprises more than a hundred of the most liquid stocks in US markets, across a broad spectrum of sectors. And while single-name investment is capped at 10% of average daily volume, this nonetheless provides investment capacity of several hundreds of millions of dollars.

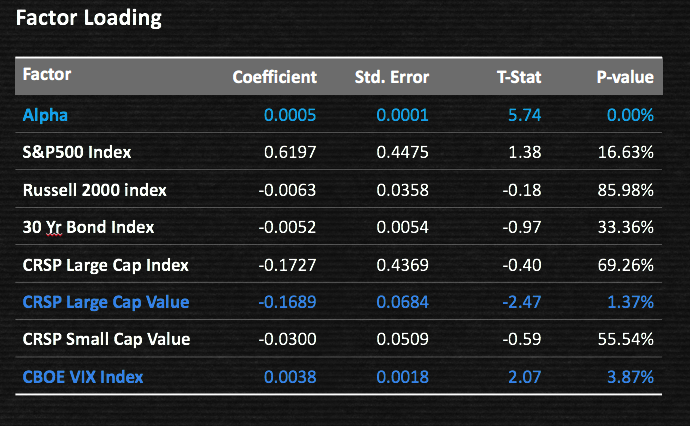

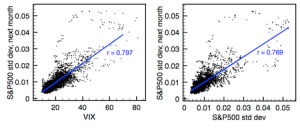

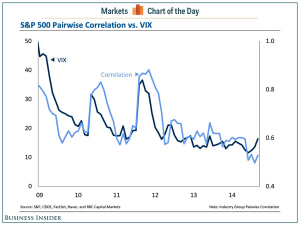

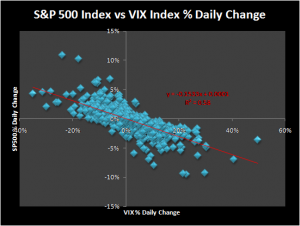

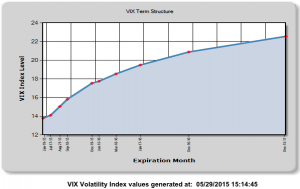

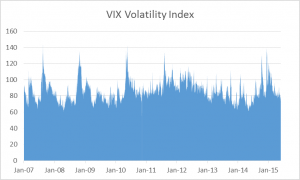

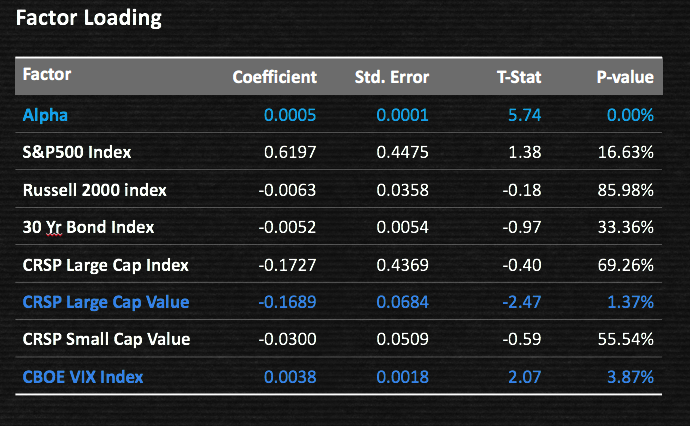

Nor does the reason for the exceptional performance lie in some new portfolio construction technique: rather, we rely on a straightforward 1/n allocation. Again, neither is factor exposure the driver of strategy alpha: as the factor loading table illustrates, strategy performance is largely uncorrelated with most market indices. It loads significantly on only large cap value, chiefly because the investment universe is defined as comprising the stocks with greatest liquidity (which tend to be large cap value), and on the CBOE VIX index. The positive correlation with market volatility is a common feature of many types of trading strategy that tend to do better in volatile markets, when short-term investment opportunities are plentiful.

While the detail of the strategy must necessarily remain proprietary, I can at least offer some insight that will, I hope, provide food for thought.

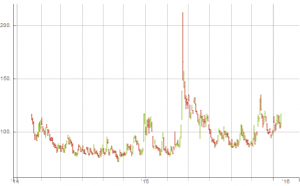

We can begin by comparing the returns for two of the stocks in the portfolio, Home Depot and Pfizer. The charts demonstrate one of important strategy characteristic: not every stock is traded at the same frequency. Some stocks might be traded once or twice a month; others possibly ten times a day, or more. In other words, the overall strategy is diversified significantly, not only across assets, but also across investment horizons. This has a considerable impact on volatility and downside risk in the portfolio.

Home Depot vs. Pfizer Inc.

Overall, the strategy trades an average of 40-60 times a day, or more. This is, admittedly, towards the low end of the frequency spectrum of HFT strategies – we might describe it as mid-frequency rather than high frequency trading. Nonetheless, compared to traditional long/short equity strategies this constitutes a high level of trading activity which, in aggregate, replicates some of the time-diversification benefits of HFT strategies, producing lower strategy volatility.

Overall, the strategy trades an average of 40-60 times a day, or more. This is, admittedly, towards the low end of the frequency spectrum of HFT strategies – we might describe it as mid-frequency rather than high frequency trading. Nonetheless, compared to traditional long/short equity strategies this constitutes a high level of trading activity which, in aggregate, replicates some of the time-diversification benefits of HFT strategies, producing lower strategy volatility.

There is another way in which the strategy mimics, at least partially, the characteristics of a HFT strategy. The profitability of many (although by no means all) HFT strategies lies in their ability to capture (or, at least, not pay) the bid-offer spread. That is why latency is so crucial to most HFT strategies – if your aim is to to earn rebates, and/or capture the spread, you must enter and exit, passively, often using microstructure models to determine when to lean on the bid or offer price. That in turn depends on achieving a high priority for your orders in the limit order book, which is a function of latency – you need to be near the top of the queue at all times in order the achieve the required fill rate.

How does that apply here? While we are not looking to capture the spread, the strategy does seek to avoid taking liquidity and paying the spread. Where it can do so, it will offset the bid-offer spread by earning rebates. In many cases we are able to mitigate the spread cost altogether. So, while it cannot accomplish what a HFT market-making system can achieve, it can mimic enough of its characteristics – even at low frequency – to produce substantial gains in terms of cost-reduction and return enhancement. This is important since the transaction volume and portfolio turnover in this approach are significantly greater than for a typical equity long/short strategy.

Portfolio of Strategies vs. Portfolio of Equities

But this feature, while important, is not really the heart of the matter. Rather, the central point is this: that the overall strategy is an assembly of individual, independent strategies for each component stock. And it turns out that the diversification benefit of a portfolio of strategies is generally far greater than for an equal number of stocks, because the equity processes themselves will typically be correlated to a far greater degree than will corresponding trading strategies. To take the example of the pair of stocks discussed earlier, we find that the correlation between HD and PFE over the period from 2013 to 2017 is around 0.39, based on daily returns. By comparison, the correlation between the strategies for the two stocks over the same period is only 0.01.

But this feature, while important, is not really the heart of the matter. Rather, the central point is this: that the overall strategy is an assembly of individual, independent strategies for each component stock. And it turns out that the diversification benefit of a portfolio of strategies is generally far greater than for an equal number of stocks, because the equity processes themselves will typically be correlated to a far greater degree than will corresponding trading strategies. To take the example of the pair of stocks discussed earlier, we find that the correlation between HD and PFE over the period from 2013 to 2017 is around 0.39, based on daily returns. By comparison, the correlation between the strategies for the two stocks over the same period is only 0.01.

This is generally the case, so that a portfolio of, say, 30 equity strategies, might reasonably be expected to enjoy a level of risk that is perhaps as much as one half that of a portfolio of the underlying stocks, no matter how constructed. This may be due to diversification in the time dimension, coupled with differences in the alpha generation mechanisms of the underlying strategies – mean reversion vs. momentum, for example

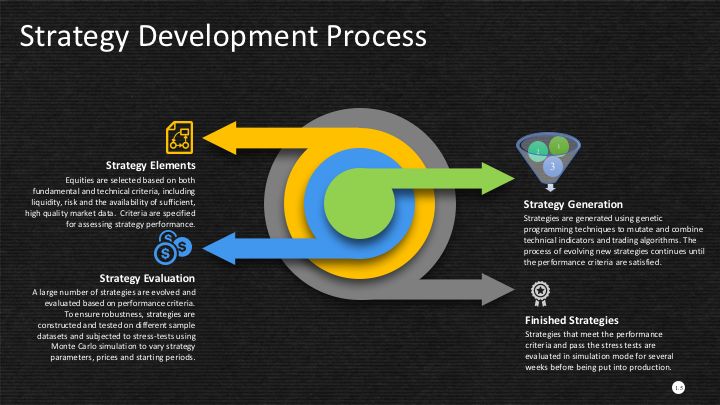

Strategy Robustness Testing

There are, of course, many different aspects to our approach to strategy risk management. Some of these are generally applicable to strategies of all varieties, but there are others that are specific to this particular type of strategy.

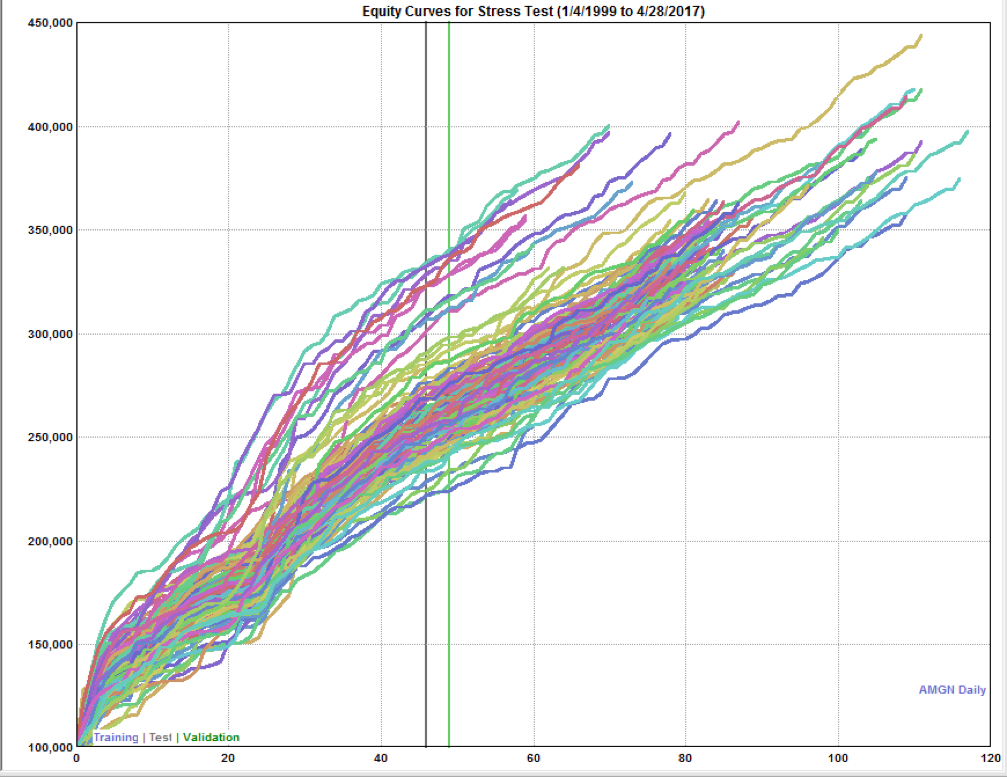

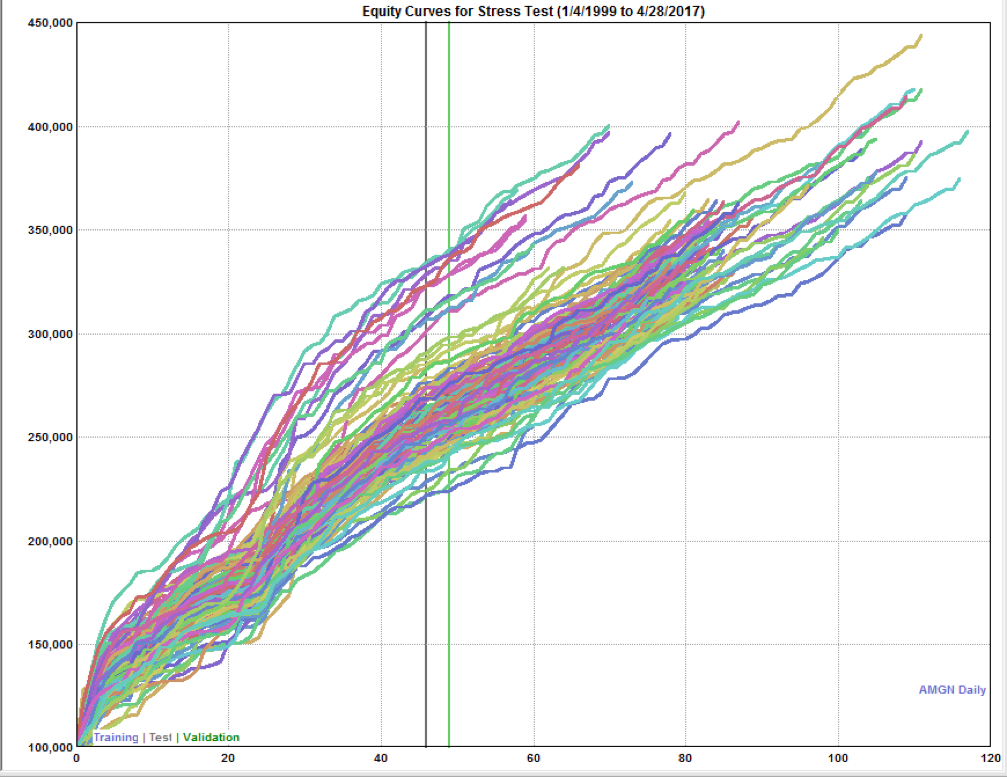

A good example of the latter is how we address the issue of strategy robustness. One of the principal concerns that investors have about quantitive strategies is that they may under-perform during adverse market conditions, or even simply stop working altogether. Our approach is to stress test each of the sub-strategy models using Monte Carlo simulation and examine their performance under a wide range of different scenarios, many of which have never been seen in the historical data used to construct the models.

For instance, we typically allow prices to fluctuate randomly by +/- 30% from historical values. But we also randomize the start date of each strategy by up to a year, which reduces the likelihood of a strategy being selected simply on the strength of a lucky start. Finally, we are interested in ensuring that the performance of each sub-strategy is not overly sensitive to the specific parameter values chosen for each model. Again, we test this using Monte Carlo, assessing the performance of each sub-strategy if the parameter values of the model are varied randomly by up to 30%.

The output of all these simulation tests is compiled into a histogram of performance results, from which we select the worst 5%-tile. Only if the worst outcomes – the 1-in-20 results in the left tail of the performance distribution – meet our performance criteria will the sub-strategy advance to the next stage of evaluation, simulated trading. This gives us – and investors – a level of confidence in the ability of the strategy to continue to perform well regardless of how market conditions evolve over time.

An obvious question to ask at this point is: if this is such a great idea, why don’t more firms use this approach? The answer is simple: it involves too much research. In a typical portfolio strategy there is a single investment idea that is applied cross-sectionally to a universe of stocks (factor models, momentum models, etc). In the strategy portfolio approach, separate strategies must be developed for each stock individually, which takes far more time and effort. Consequently such strategies must necessarily scale more slowly.

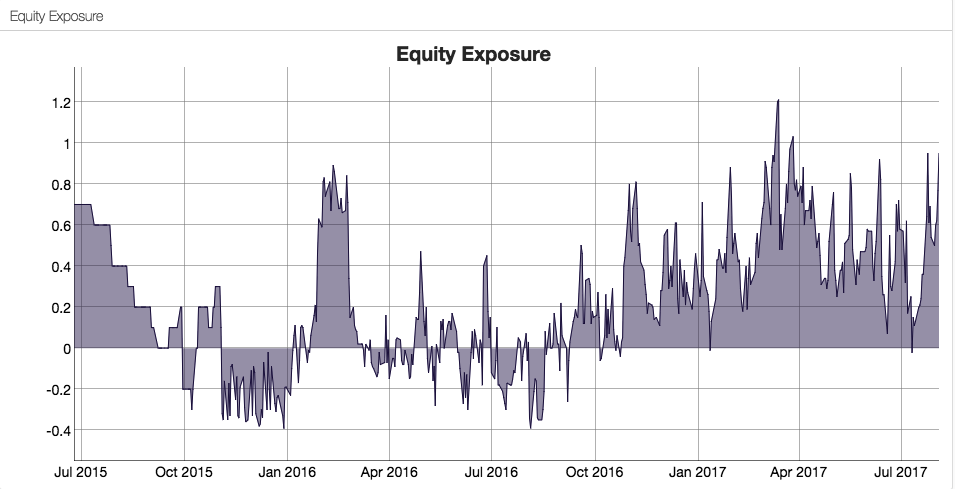

Another downside to the strategy portfolio approach is that it is less able to control the portfolio characteristics. For instance, the overall portfolio may, on average, have a beta close to zero; but there are likely to be times when a majority of the individual stock strategies align, producing a significantly higher, or lower, beta. The key here is to ask the question: what matters more – the semblance of risk control, or the actual risk characteristics of the strategy? In reality, the risk controls of traditional long/short equity strategies often turn out to be more theoretical than real. Time and again investors have seen strategies that turn out to be downside-correlated with the market, regardless of the purported “market-neutral” characteristics of the portfolio. I would argue that what matters far more is how the strategy actually performs under conditions of market stress, regardless of how “market neutral” or “sector neutral” it may purport to be. And while I agree that this is hardly a widely-held view, my argument would be that one cannot expect to achieve above-average performance simply by employing standard approaches at every turn.

Parallels with Fund of Funds Investment

So, is this really a “new approach” to equity long/short? Actually, no. It is certainly unusual. But it follows quite closely the model of a proprietary trading firm, or a Fund of Funds. There, as here, the task is to create a combined portfolio of strategies (or managers), rather than by investing directly in the underlying assets. A Fund of Funds will seek to create a portfolio of strategies that have low correlations to one another, and may operate a meta-strategy for allocating capital to the component strategies, or managers. But the overall investment portfolio cannot be as easily constrained as an individual equity portfolio can be – greater leeway must be allowed for the beta, or the dollar imbalance in the longs and shorts, to vary from time to time, even if over the long term the fluctuations average out. With human managers one always has to be concerned about the risk of “style drift” – i.e. when managers move away from their stated investment mandate, methodologies or objectives, resulting in a different investment outcomes. This can result in changes in the correlation between a strategy and its peers, or with the overall market. Quantitative strategies are necessarily more consistent in their investment approach – machines generally don’t alter their own source code – making a drift in style less likely. So an argument can be made that the risk inherent in this form of equity long/short strategy is on a par with – certainly not greater than – that of a typical fund of funds.

Conclusions

An investment approach that seeks to create a portfolio of strategies, rather than of underlying assets, offers a significant advantage in terms of risk reduction and diversification, due to the relatively low levels of correlation between the component strategies. The trading costs associated with higher frequency trading can be mitigated using passive entry/exit rules designed to avoid taking liquidity and generating exchange rebates. The downside is that it is much harder to manage the risk attributes of the portfolio, such as the portfolio beta, sector risk, or even the overall net long/short exposure. But these are indicators of strategy risk, rather than actual risk itself and they often fail to predict the actual risk characteristics of the strategy, especially during conditions of market stress. Investors may be better served by an approach to long/short equity that seeks to maximize diversification on the temporal axis as well as in terms of the factors driving strategy alpha.

Disclaimer: past performance does not guarantee future results. You should not rely on any past performance as a guarantee of future investment performance. Investment returns will fluctuate. Investment monies are at risk and you may suffer losses on any investment.