Single Stock Analytics

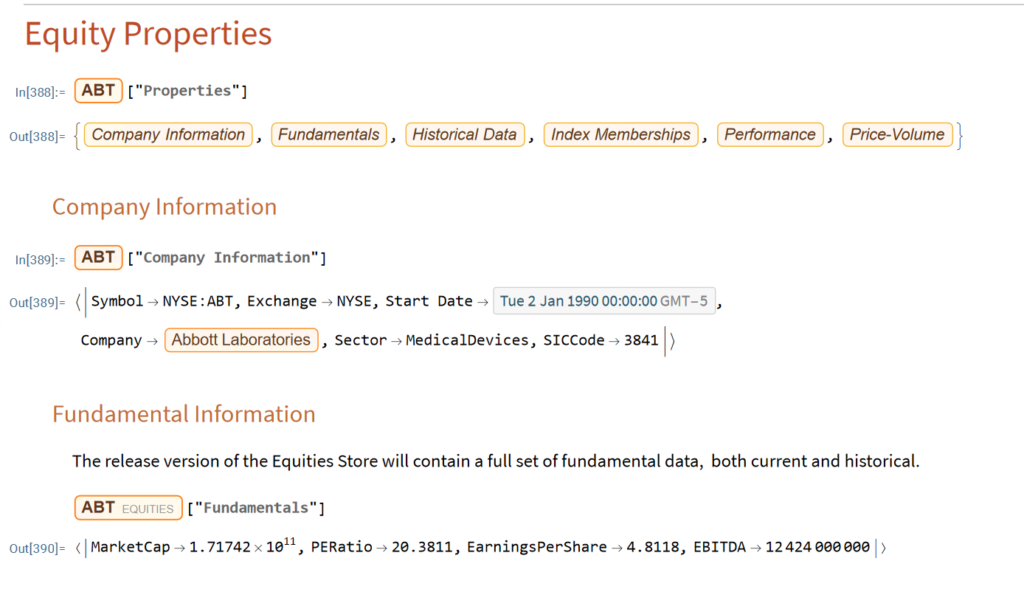

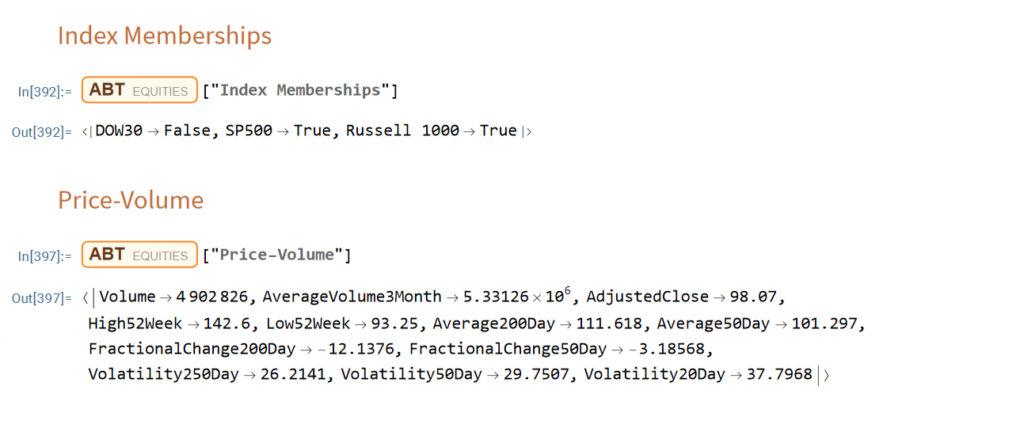

Generally speaking, one of the major attractions of working in the equities space is that the large number of available securities opens up a much wider range of opportunities for the quantitative researcher than for, say, futures markets. The focus in equities tends to be on portfolio strategies since the scope of the universe permits an unparalleled degree of diversification. Single stock strategies forego such benefit, but they are of interest to the analyst and investor nonetheless: “stock picking” is almost a national pastime, at least for US investors.

Rather than seeking to mitigate stock specific risk through diversification, the stock picker is actively seeking to identify risk opportunities that are unique to a specific stock, and he hopes will yield abnormal returns. These can arise for any number of reasons – mergers and acquisitions, new product development, change in index membership, to name just a few. The hope is that such opportunities may be uncovered by one of several possible means:

- Identification of latent, intrinsic value in neglected stocks that has been overlooked by other analysts

- The use of alternative types of data that permits new insight in the potential of a specific stock or group of stocks

- A novel method of analysis that reveals hitherto hidden potential in a particular stock or group of stocks

One can think of examples of each of these possibilities, but at the same time it has to be admitted that the challenge is very considerable. Firstly, your discovery or methodology would have to be one that has eluded some of the brightest minds in the investment industry. That has happened in the past and will no doubt occur again in future; but the analyst has to have a fairly high regard for his own intellect – or good fortune – to believe that the golden apple will fall into his lap, rather than another’s. Secondly there is the question of the efficient market hypothesis. These days it is fashionable to pour scorn on the EMH, with examples of well-known anomalies often used to justify the opprobrium. But the EMH doesn’t say that markets are 100% efficient, 100% of the time. It says that markets are efficient, on average. This means that there will be times or circumstances in which the market will be efficient and other times and circumstances when it will be relatively inefficient – but you won’t be able to discern which condition the market is in currently. Finally, even if one is successful in identifying such an opportunity, the benefit has to be realizable and economically significant. I can think of several examples of equity strategies that appear to offer the potential to generate alpha, but which turn out to be either unrealizable or economically insignificant after applying transaction costs.

All this is to say that stock picking is one of the most difficult challenges the analyst can undertake. It is also one of the most interesting challenges – and best paid occupations – on Wall Street. So it is unsurprising that for analysts it remains the focus of their research and ambition. In this chapter we will look at some of the ways in which the Equities Entity Store can be used for such purposes and some of the more interesting analytical methods.

Why Technical Analysis Doesn’t Work

Technical Analysis is a very popular approach to analysing stocks. Unfortunately, it is also largely useless, at least if the intention is to uncover potential sources of alpha. The reason is not hard to understand: it relies on applying analytical methods that have been known for decades to widely available public information (price data). There isn’t any source of competitive advantage that might reliably produce abnormal returns. Even the possibility of uncovering a gem amongst the stocks overlooked by other analysts appears increasingly remote these days, as the advent of computerized trading systems has facilitated the application of standard technical analysis tools on an industrial scale. You don’t even need to understand how the indicators work – much less how to program them – in order to apply them to tens of thousands of stocks.

And yet Technical Analysis remains very popular. Why so? The answer, I believe, is because it’s easy to do and can often look very pretty. I will go further and admit that some of the indicators that analysts have devised are extraordinarily creative. But they just don’t work. In fact, I can’t think of another field of human industry that engages so many inventive minds in such a fruitless endeavor.

All this has been clear for some time and yet every year legions of newly minted analysts fling themselves into the task of learning how to apply Technical Analysis to everything from cattle futures to cryptocurrencies. Realistically, the chances of my making any kind of impression on this torrent of pointless hyperactivity are close to zero, but I will give it a go.

A Demonstration

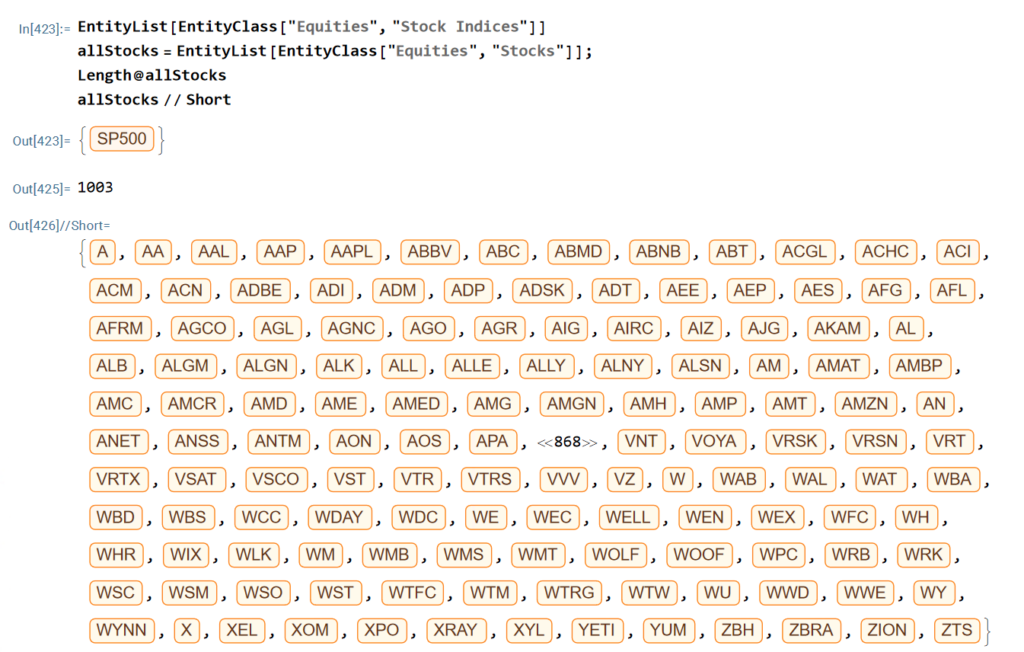

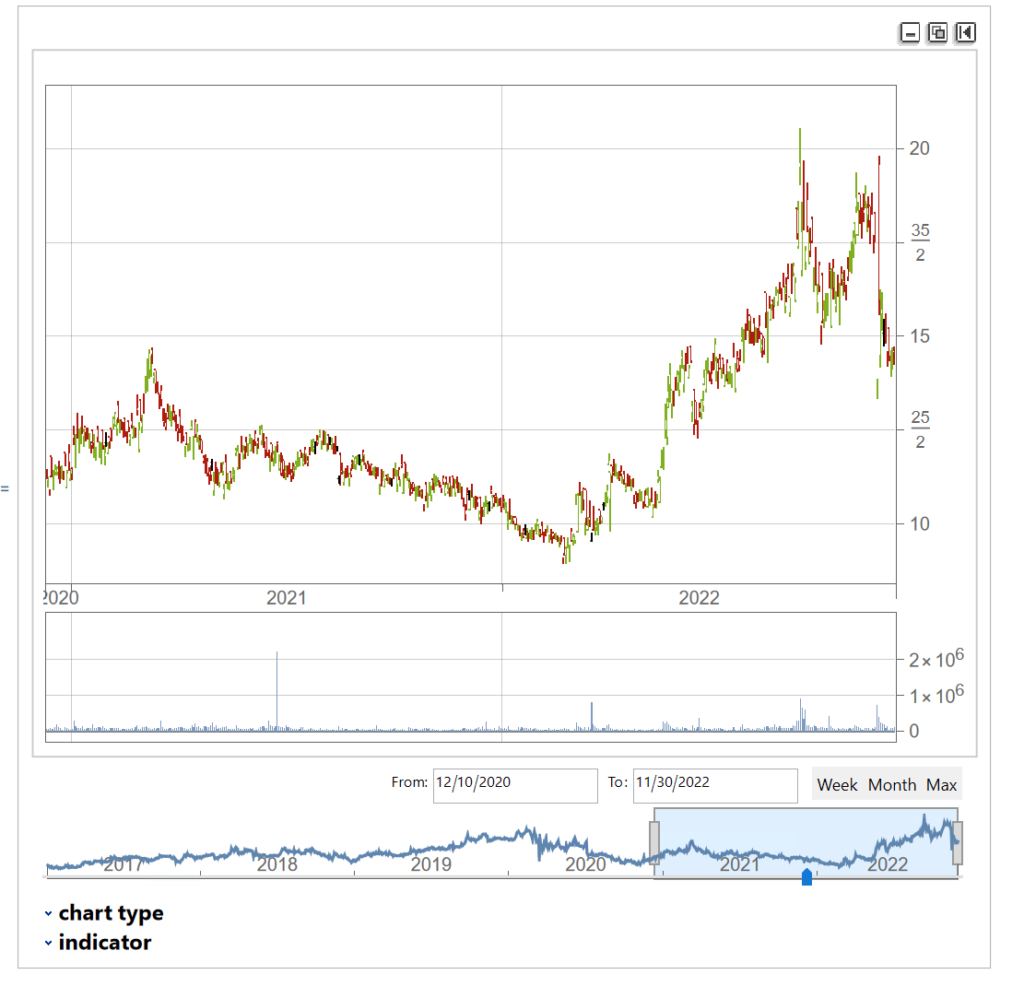

Let’ s begin by picking a stock at random, one I haven’ t look at previously :

waterUtilities=Select[allListedStocks,#["Sector Information"]["GICS Industry"]== "Water Utilities"&]

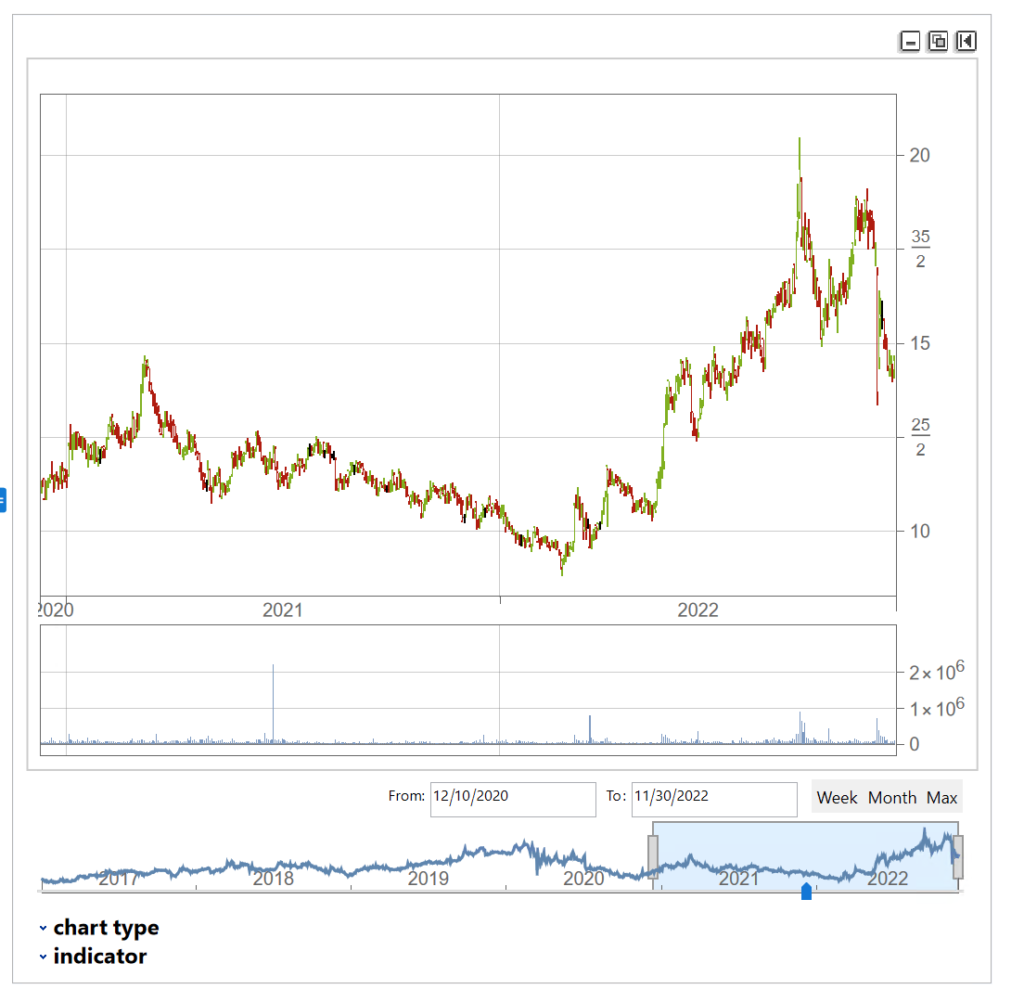

We’ll extract a daily price series from 2017 to 2022 and plot an interactive trading chart, to which we can add moving averages, or any number of other technical indicators, as we wish:

The chart shows several different types of pattern that are well-known to technical analysis, including trends, continuation patterns, gaps, double tops, etc

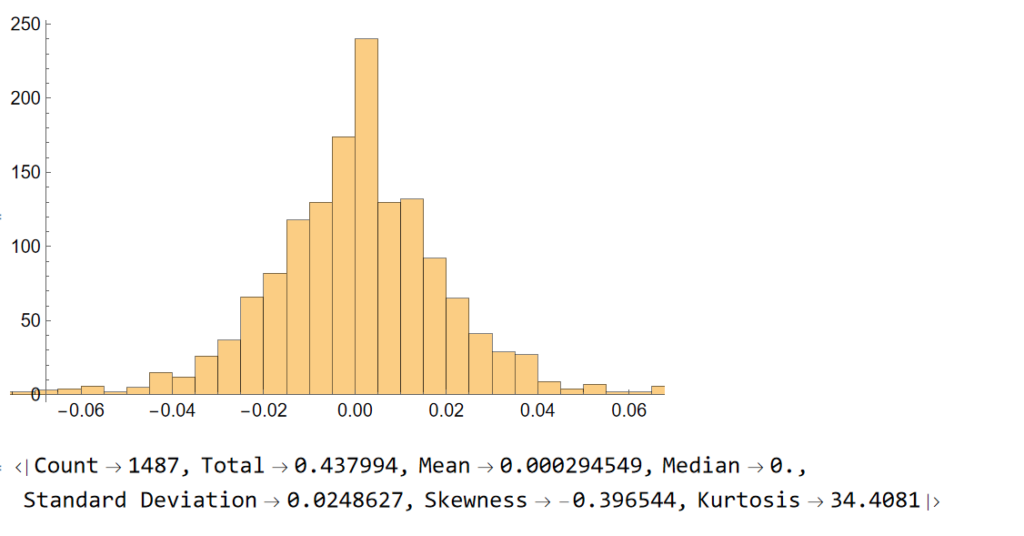

Let’ s look at the pattern of daily returns:

returns=Differences@Log[tsCWCO["PathComponent",4]["Values"]]; Histogram[returns] stats=ReturnStatistics[returns]

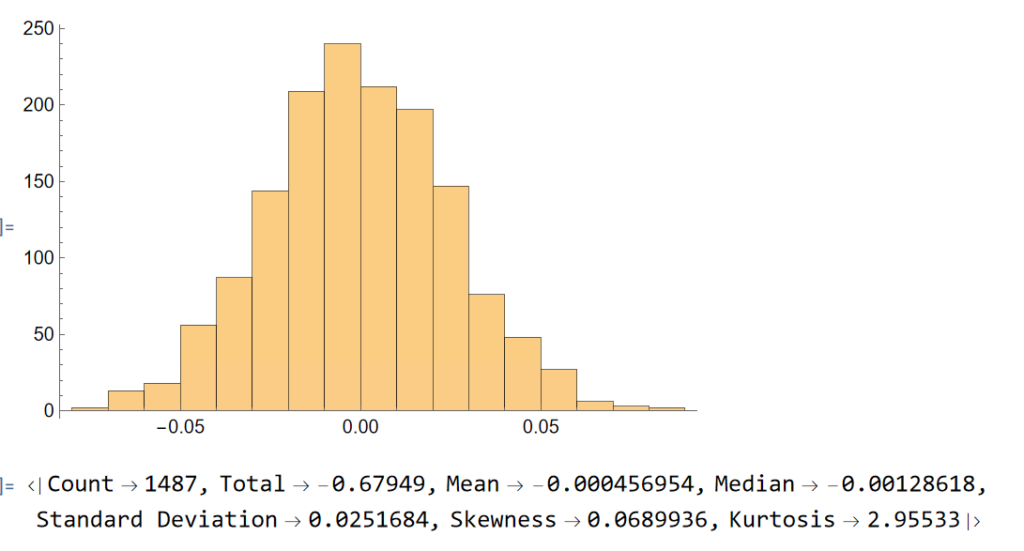

Next, we will generate a series of random returns, drawn from a Gaussian distribution with the same mean and standard deviation as the empirical returns series:

randomreturns=RandomVariate[NormalDistribution[stats["Mean"],stats["Standard Deviation"]],Length[returns]];

Histogram[randomreturns]

ReturnStatistics[randomreturns]

Clearly, the distribution of the generated returns differs from the distribution of empirical returns, but that doesn’t matter: all that counts is that we can agree that the generated returns, which represent the changes in (log) prices from one day to the next, are completely random. Consequently, knowing the random returns, or prices, at time t = 1, 2, . . . , (t-1) in no way enables you to forecast the return , or price, at time t.

Now let’ s generate a series of synthetic prices and time series, using the synthetic returns to calculate the prices for each period:

syntheticPrices=Exp[FoldList[Plus,Log[First[tsCWCO["FirstValues"]][[1;;4]]],Transpose[ConstantArray[returns,4]]]];

tsSynthetic=TimeSeries[ArrayFlatten@{{syntheticPrices,List/@tsCWCO["PathComponent",5]["Values"]}},{tsCWCO["Dates"]}]

InteractiveTradingChart[tsSynthetic]

The synthetic time series is very similar to the original and displays many of the same characteristics, including classical patterns that are immediately comprehensible to a technical analyst, such as gaps, reversals , double tops, etc.

But the two time series, although similar, are not identical:

tsCWCO===tsSynthetic

False

We knew this already, of course, because we used randomly generated returns to create the synthetic price series. What this means is that, unlike for the real price series, in the case of the synthetic price series we know for certain that the movement in prices from one period to the next is entirely random. So if prices continue in an upward trend after a gap, or decline after a double top formation appears on the chart of the synthetic series, that happens entirely by random chance, not in response to a pattern flagged by the technical indicator. If we had generated a different set of random returns, we could just as easily have produced a synthetic price series in which prices reversed after a gap up, or continued higher after a double-top formation. Critics of Technical Analysis do not claim that patterns such as gaps, head and shoulders , etc., do not exist – they clearly do. Rather, we say that such patterns are naturally occurring phenomena that will arise even in a series known to be completely random and hence can have no economic significance.

The point is not to say that technical signals never work: sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t. Rather, the point is that, in any given situation, you will be unable to tell whether the signal is going to work this time, or not – because price changes are dominated by random variation.

You can make money in the markets using technical analysis, just as you can by picking stocks at random, throwing darts at a dartboard, or tossing a coin to decide which to buy or sell – i.e. by dumb luck. But you can’t reliably make money this way.

- More on the efficient market hypothesis

- More from the Society of Technical Analysts