An extract from my new book, Equity Analytics.

Trading-Anomalies-2The Amazon Killer

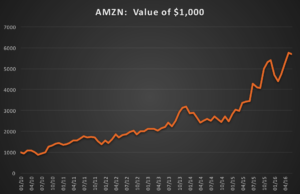

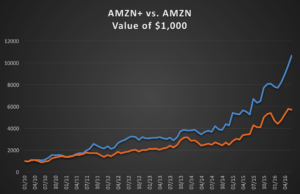

Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) has been on a tear over the last decade, especially since the financial crisis of 2008. If you had been smart (or lucky) enough to buy the stock at the beginning of 2010, each $1,000 you invested would now be worth over $5,700, giving a CAGR of over 31%.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

It’s hard to argue with success, but could you have done better? The answer, surprisingly, is yes – and by a wide margin.

Introducing AMZN+

I am going to reveal this mystery stock in due course and, I promise you, the investment recommendation is fully actionable. For now, let’s just refer to it as AMZN+.

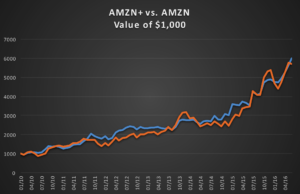

A comparison between investments made in AMZN and AMZN+ over the period from January 2010 to June 2016 is shown the chart following.

Visually, there doesn’t appear to be much of a difference in overall performance. However, it is apparent that AMZN+ is a great deal less volatile than its counterpart.

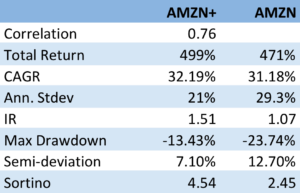

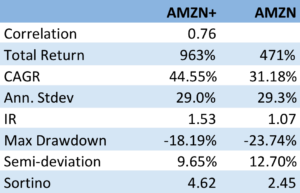

The table below give a more telling account of the relative outperformance by AMZN+.

The two investments are very highly correlated, with AMZN+ producing an extra 1% per annum in CAGR over the 6 ½ year period.

The telling distinction, however, lies on the risk side of the equation. Here AMZN+ outperforms AMZN by a wide margin, with an annual standard deviation of only 21% compared to 29%. What this means is that AMZN+ produces almost a 50% higher return than AMZN per unit of risk (information ratio 1.51 vs. 1.07).

The more conservative risk profile of AMZN+ is also reflected in lower maximum drawdown (-13.43% vs -23.74%), semi-deviation and higher Sortino Ratio (see this article for an explanation of these terms).

Bottom line: you can produce around the same rate of return with substantially less risk by investing in AMZN+, rather than AMZN.

Comparing Equally Risky Investments

There is another way to make the comparison, which some investors might find more appealing. Risk is, after all, an altogether more esoteric subject than return, which every investor understands.

So let’s say the investor adopts the same risk budget as for his original investment in AMZN, i.e. an annual volatility of just over 29%. We can produce the same overall level of risk in AMZN+, equalizing the riskiness of the two investments, simply by leveraging the investment in AMZN+ by a factor of 1.36, using margin money. i.e. we borrow $360 and invest a total of $1,360 in AMZN+, for each $1,000 we would have invested in AMZN. Look at the difference in performance:

The investor’s total return in AMZN+ would have been 963%, almost double the return in AMZN over the same period and with a CAGR of over 44.5%, more than 13% per annum higher than AMZN.

Note that, despite having an almost identical annual standard deviation, AMZN+ still enjoys a lower maximum drawdown and downside risk than AMZN.

The Big Reveal

Ok, so what is this mystery stock, AMZN+? Actually it isn’t a stock: it’s a simple portfolio, rebalanced monthly, with 66% of the investment being made in AMZN and 34% in the Direxion Daily 20+ Yr Trsy Bull 3X ETF (NYSEArca: TMF).

Well, that’s a little bit of a cheat, although not much of one: it isn’t too much of a challenge to put $667 of every $1,000 in AMZN and the remaining $333 in TMF, rebalancing the portfolio at the end of every month.

The next question an investor might want to ask is: what other stocks could I apply this approach to? The answer is: a great many of them. And where you end up, ultimately, is with the discovery that you can eliminate a great deal of unnecessary risk with a portfolio of around 20-30 well-chosen assets.

The Fundamental Lesson from Portfolio Theory

We saw that AMZN incurred a risk of 29% in annual standard deviation, compared to only 21% for the AMZN+ portfolio. What does the investor gain by taking that extra 8% in annual risk? Nothing at all – in fact he would have achieved a slightly worse return.

The key take-away from this simple example is the fundamental law of modern portfolio theory:

The market will not compensate an investor for taking diversifiable risk

As they say, diversification is the only free lunch on Wall Street. So make the most of it.

What Wealth Managers and Family Offices Need to Understand About Alternative Investing

The most recent Morningstar survey provides an interesting snapshot of the state of the alternatives market. In 2013, for the third successive year, liquid alternatives was the fastest growing category of mutual funds, drawing in flows totaling $95.6 billion. The fastest growing subcategories have been long-short stock funds (growing more than 80% in 2013), nontraditional bond funds (79%) and “multi-alternative” fund-of-alts-funds products (57%).

Benchmarking Alternatives

The survey also provides some interesting insights into the misconceptions about alternative investments that remain prevalent amongst advisors, despite contrary indications provided by long-standing academic research. According to Morningstar, a significant proportion of advisors continue to use inappropriate benchmarks, such as the S&P 500 or Russell 2000, to evaluate alternatives funds (see Some advisers using ill-suited benchmarks to measure alts performance by Trevor Hunnicutt, Investment News July 2014). As Investment News points out, the problem with applying standards developed to measure the performance of funds that are designed to beat market benchmarks is that many alternative funds are intended to achieve other investment goals, such as reducing volatility or correlation. These funds will typically have under-performed standard equity indices during the bull market, causing investors to jettison them from their portfolios at a time when the additional protection they offer may be most needed.

This is but one example in a broader spectrum of issues about alternative investing that are poorly understood. Even where advisors recognize the need for a more appropriate hedge fund index to benchmark fund performance, several traps remain for the unwary. As shown in Brooks and Kat (The Statistical Properties of Hedge Fund Index Returns and Their Implications for Investors, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 2001), there can be considerable heterogeneity between indices that aim to benchmark the same type of strategy, since indices tend to cover different parts of the alternatives universe. There are also significant differences between indices in terms of their survivorship bias – the tendency to overstate returns by ignoring poorly performing funds that have closed down (see Welcome to the Dark Side – Hedge Fund Attribution and Survivorship Bias, Amin and Kat, Working Paper, 2002). Hence, even amongst more savvy advisors, the perception of performance tends to be biased by the choice of index.

Risks and Benefits of Diversifying with Alternatives

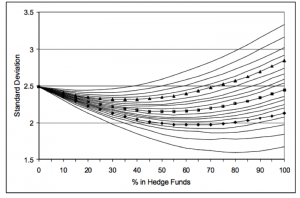

An important and surprising discovery in relation to diversification with alternatives was revealed in Amin and Kat’s Diversification and Yield Enhancement with Hedge Funds (Working Paper, 2002). Their study showed that the median standard deviation of a portfolio of stocks, bonds and hedge funds reached its lowest point where the allocation to alternatives was 50%, far higher than the 1%-5% typically recommended by advisors.

Standard Deviation of Portfolios of Stocks, Bonds and 20 hedge Funds

Source: Diversification and Yield Enhancement with Hedge Funds, Amin and Kat, Working Paper, 2002

Another potential problem is that investors will not actually invest in the fund index that is used for benchmarking, but in a basket containing a much smaller number of funds, often through a fund of funds vehicle. The discrepancy in performance between benchmark and basket can often be substantial in the alternatives space.

Amin and Kat studied this problem in 2002 (Portfolios of Hedge Funds, Working Paper, 2002), by constructing hedge fund portfolios ranging in size from 1 to 20 funds and measuring their performance on a number of criteria that included, not just the average return and standard deviation, but also the skewness (a measure of the asymmetry of returns), kurtosis (a measure of the probability of extreme returns)and the correlation with the S&P 500 Index and the Salomon (now Citigroup) Government Bond Index. Their startling conclusion was that, in the alternatives space, diversification is not necessarily a good thing. As expected, as the number of funds in the basket is increased, the overall volatility drops substantially; but at the same time skewness drops and kurtosis and market correlation increase significantly. In other words, when adding more funds, the likelihood of a large loss increases and the diversification benefit declines. The researchers found that a good approximation to a typical hedge fund index could be constructed with a basket of just 15 well-chosen funds, in most cases.

Concerns about return distribution characteristics such as skewness and kurtosis may appear arcane, but these factors often become crucially important at just the wrong time, from the investor’s perspective. When things go wrong in the stock market they also tend to go wrong for hedge funds, as a fall in stock prices is typically accompanied by a drop in market liquidity, a widening of spreads and, often, an increase in stock loan costs. Equity market neutral and long/short funds that are typically long smaller cap stocks and short larger cap stocks will pay a higher price for the liquidity they need to maintain neutrality. Likewise, a market sell-off is likely to lead to postponing of M&A transactions that will have a negative impact on the performance of risk arbitrage funds. Nor are equity-related funds the only alternatives likely to suffer during a market sell-off. A market fall will typically be accompanied by widening credit spreads, which in turn will damage the performance of fixed income and convertible arbitrage funds. The key point is that, because they all share this risk, diversification among different funds will not do much to mitigate it.

Conclusions

Many advisors remain wedded to using traditional equity indices that are inappropriate benchmarks for alternative strategies. Even where more relevant indices are selected, they may suffer from survivorship and fund-selection bias.

In order to reap the diversification benefit from alternatives, research shows that investors should concentrate a significant proportion of their wealth in the limited number of alternatives funds, a portfolio strategy that is diametrically opposed to the “common sense” approach of many advisors.

Finally, advisors often overlook the latent correlation and liquidity risks inherent in alternatives that come into play during market down-turns, at precisely the time when investors are most dependent on diversification to mitigate market risk. Such risks can be managed, but only by paying attention to portfolio characteristics such as skewness and kurtosis, which alternative funds significantly impact.