High Frequency Scalping Strategies

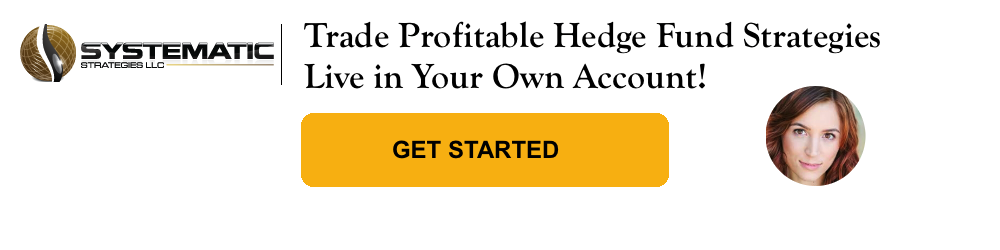

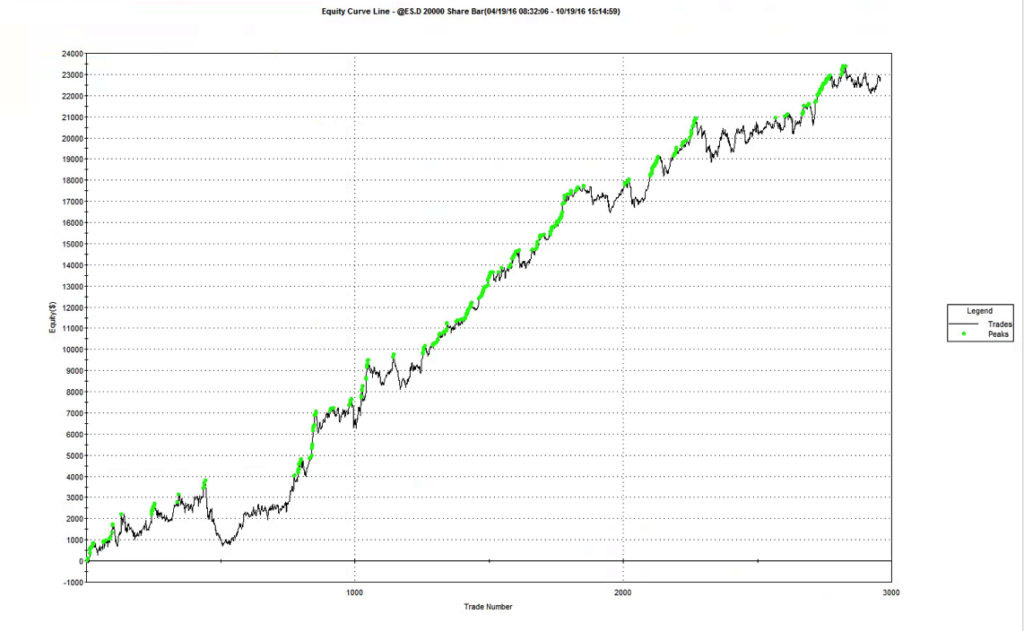

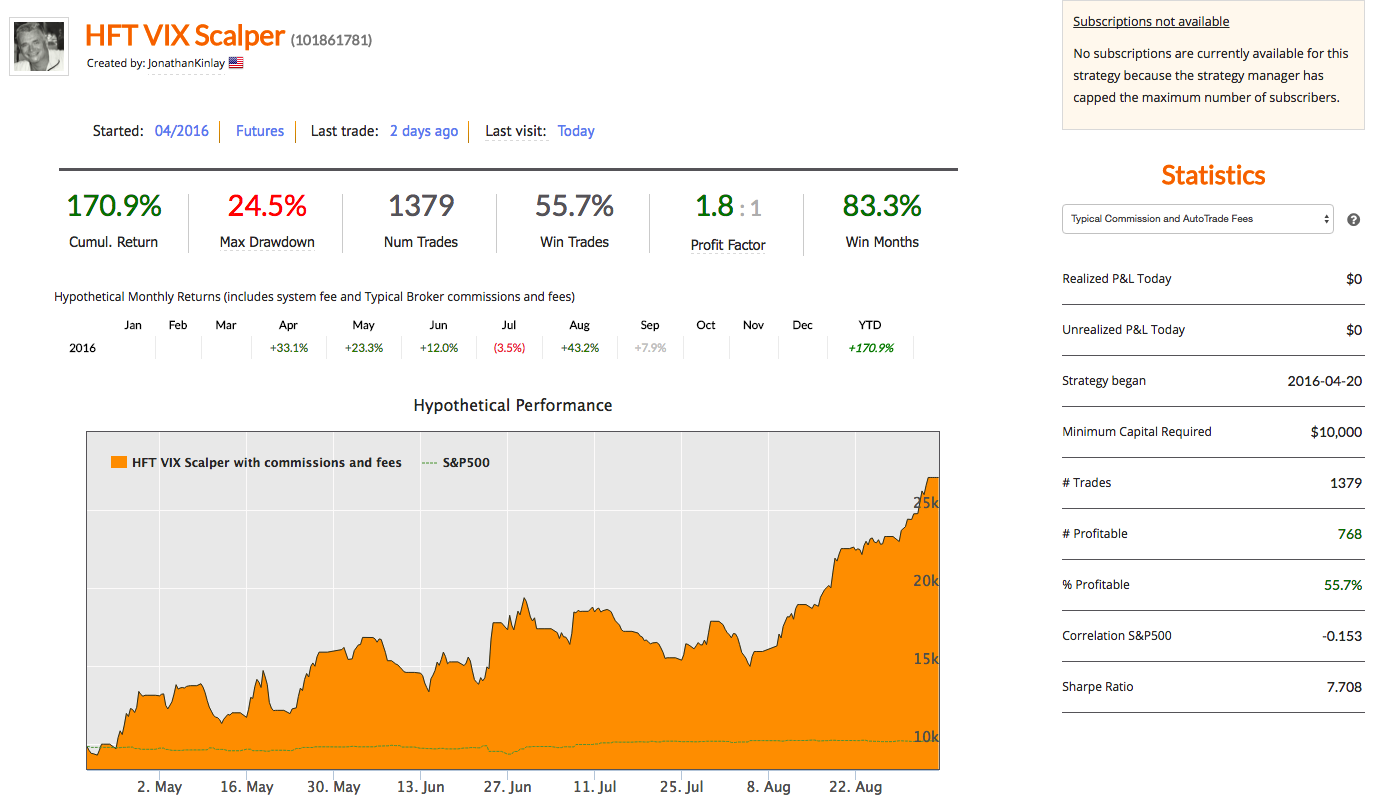

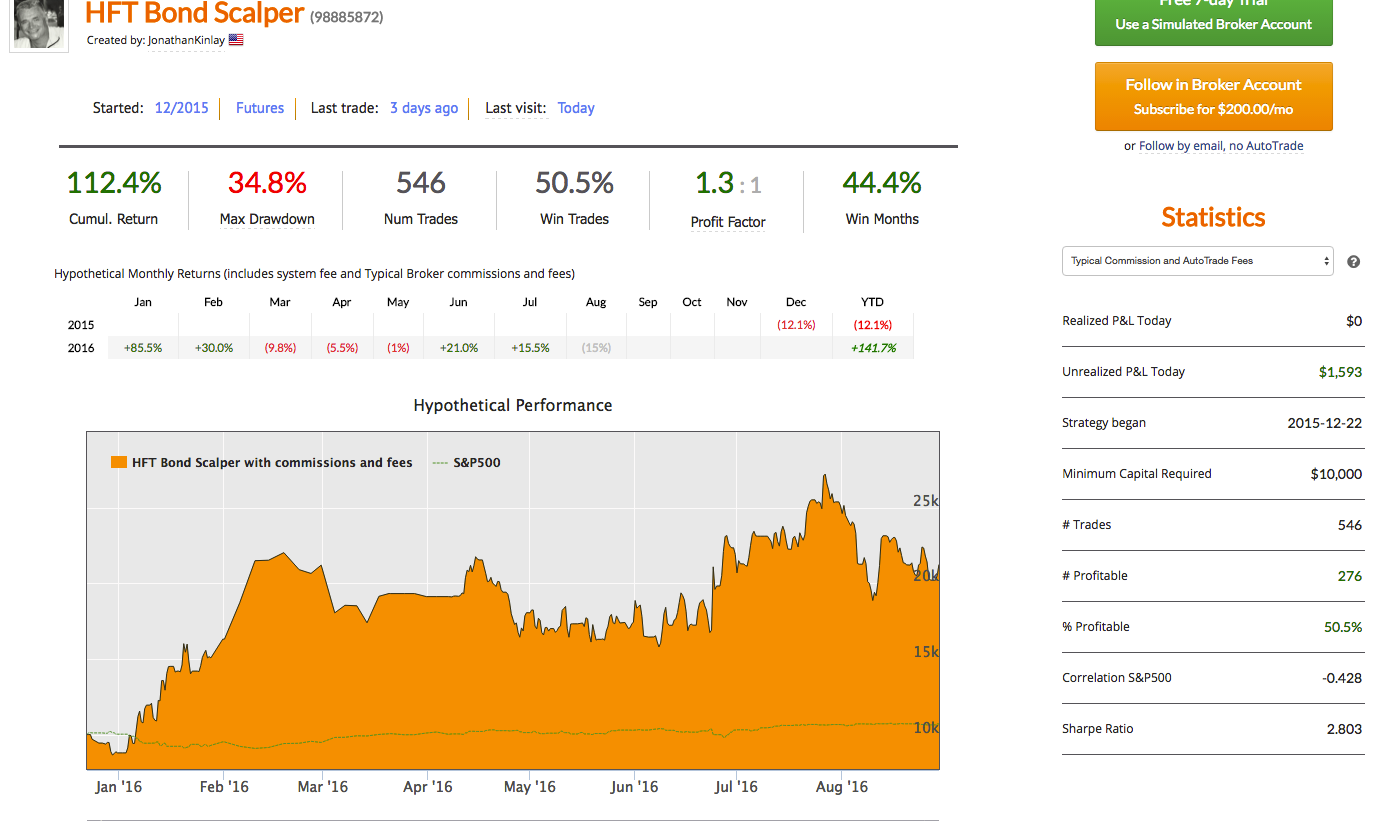

HFT scalping strategies enjoy several highly desirable characteristics, compared to low frequency strategies. A case in point is our scalping strategy in VIX futures, currently running on the Collective2 web site:

- The strategy is highly profitable, with a Sharpe Ratio in excess of 9 (net of transaction costs of $14 prt)

- Performance is consistent and reliable, being based on a large number of trades (10-20 per day)

- The strategy has low, or negative correlation to the underlying equity and volatility indices

- There is no overnight risk

Background on HFT Scalping Strategies

The attractiveness of such strategies is undeniable. So how does one go about developing them?

It is important for the reader to familiarize himself with some of the background to high frequency trading in general and scalping strategies in particular. Specifically, I would recommend reading the following blog posts:

http://jonathankinlay.com/2015/05/high-frequency-trading-strategies/

http://jonathankinlay.com/2014/05/the-mathematics-of-scalping/

Execution vs Alpha Generation in HFT Strategies

The key to understanding HFT strategies is that execution is everything. With low frequency strategies a great deal of work goes into researching sources of alpha, often using highly sophisticated mathematical and statistical techniques to identify and separate the alpha signal from the background noise. Strategy alpha accounts for perhaps as much as 80% of the total return in a low frequency strategy, with execution making up the remaining 20%. It is not that execution is unimportant, but there are only so many basis points one can earn (or save) in a strategy with monthly turnover. By contrast, a high frequency strategy is highly dependent on trade execution, which may account for 80% or more of the total return. The algorithms that generate the strategy alpha are often very simple and may provide only the smallest of edges. However, that very small edge, scaled up over thousands of trades, is sufficient to produce a significant return. And since the risk is spread over a large number of very small time increments, the rate of return can become eye-wateringly high on a risk-adjusted basis: Sharpe Ratios of 10, or more, are commonly achieved with HFT strategies.

In many cases an HFT algorithm seeks to estimate the conditional probability of an uptick or downtick in the underlying, leaning on the bid or offer price accordingly. Provided orders can be positioned towards the front of the queue to ensure an adequate fill rate, the laws of probability will do the rest. So, in the HFT context, much effort is expended on mitigating latency and on developing techniques for establishing and maintaining priority in the limit order book. Another major concern is to monitor order book dynamics for signs that book pressure may be moving against any open orders, so that they can be cancelled in good time, avoiding adverse selection by informed traders, or a buildup of unwanted inventory.

In a high frequency scalping strategy one is typically looking to capture an average of between 1/2 to 1 tick per trade. For example, the VIX scalping strategy illustrated here averages around $23 per contract per trade, i.e. just under 1/2 a tick in the futures contract. Trade entry and exit is effected using limit orders, since there is no room to accommodate slippage in a trading system that generates less than a single tick per trade, on average. As with most HFT strategies the alpha algorithms are only moderately sophisticated, and the strategy is highly dependent on achieving an acceptable fill rate (the proportion of limit orders that are executed). The importance of achieving a high enough fill rate is clearly illustrated in the first of the two posts referenced above. So what is an acceptable fill rate for a HFT strategy?

Fill Rates

I’m going to address the issue of fill rates by focusing on a critical subset of the problem: fills that occur at the extreme of the bar, also known as “extreme hits”. These are limit orders whose prices coincide with the highest (in the case of a sell order) or lowest (in the case of a buy order) trade price in any bar of the price series. Limit orders at prices within the interior of the bar are necessarily filled and are therefore uncontroversial. But limit orders at the extremities of the bar may or may not be filled and it is therefore these orders that are the focus of attention.

By default, most retail platform backtest simulators assume that all limit orders, including extreme hits, are filled if the underlying trades there. In other words, these systems typically assume a 100% fill rate on extreme hits. This is highly unrealistic: in many cases the high or low of a bar forms a turning point that the price series visits only fleetingly before reversing its recent trend, and does not revisit for a considerable time. The first few orders at the front of the queue will be filled, but many, perhaps the majority of, orders further down the priority order will be disappointed. If the trader is using a retail trading system rather than a HFT platform to execute his trades, his limit orders are almost always guaranteed to rest towards the back of the queue, due to the relatively high latency of his system. As a result, a great many of his limit orders – in particular, the extreme hits – will not be filled.

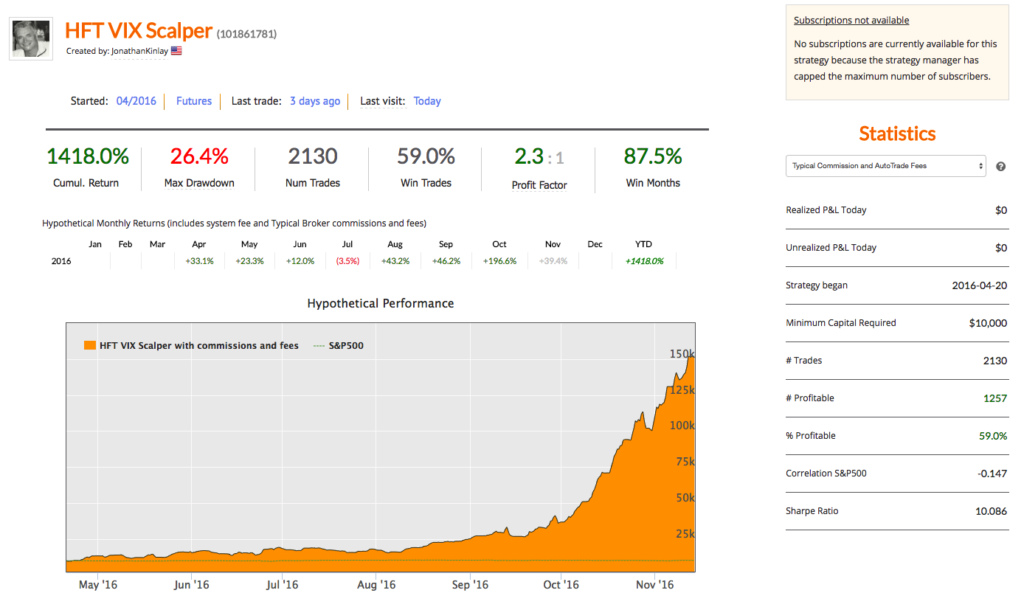

The consequences of missing a large number of trades due to unfilled limit orders are likely to be catastrophic for any HFT strategy. A simple test that is readily available in most backtest systems is to change the underlying assumption with regard to the fill rate on extreme hits – instead of assuming that 100% of such orders are filled, the system is able to test the outcome if limit orders are filled only if the price series subsequently exceeds the limit price. The outcome produced under this alternative scenario is typically extremely adverse, as illustrated in first blog post referenced previously.

In reality, of course, neither assumption is reasonable: it is unlikely that either 100% or 0% of a strategy’s extreme hits will be filled – the actual fill rate will likely lie somewhere between these two outcomes. And this is the critical issue: at some level of fill rate the strategy will move from profitability into unprofitability. The key to implementing a HFT scalping strategy successfully is to ensure that the execution falls on the right side of that dividing line.

Implementing HFT Scalping Strategies in Practice

One solution to the fill rate problem is to spend millions of dollars building HFT infrastructure. But for the purposes of this post let’s assume that the trader is confined to using a retail trading platform like Tradestation or Interactive Brokers. Are HFT scalping systems still feasible in such an environment? The answer, surprisingly, is a qualified yes – by using a technique that took me many years to discover.

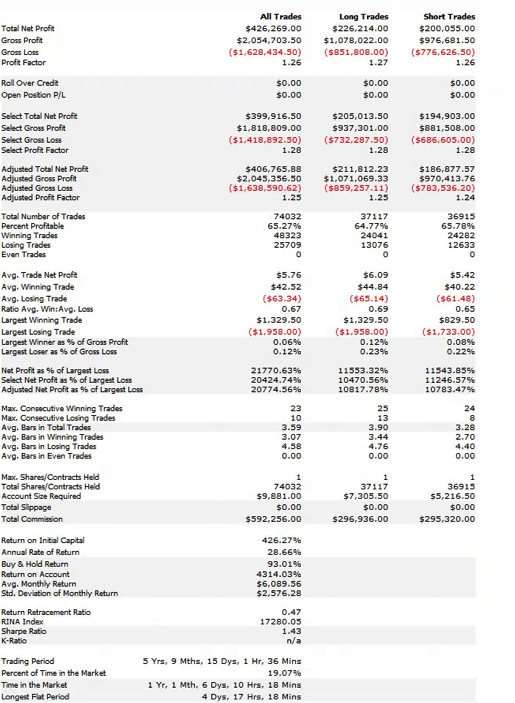

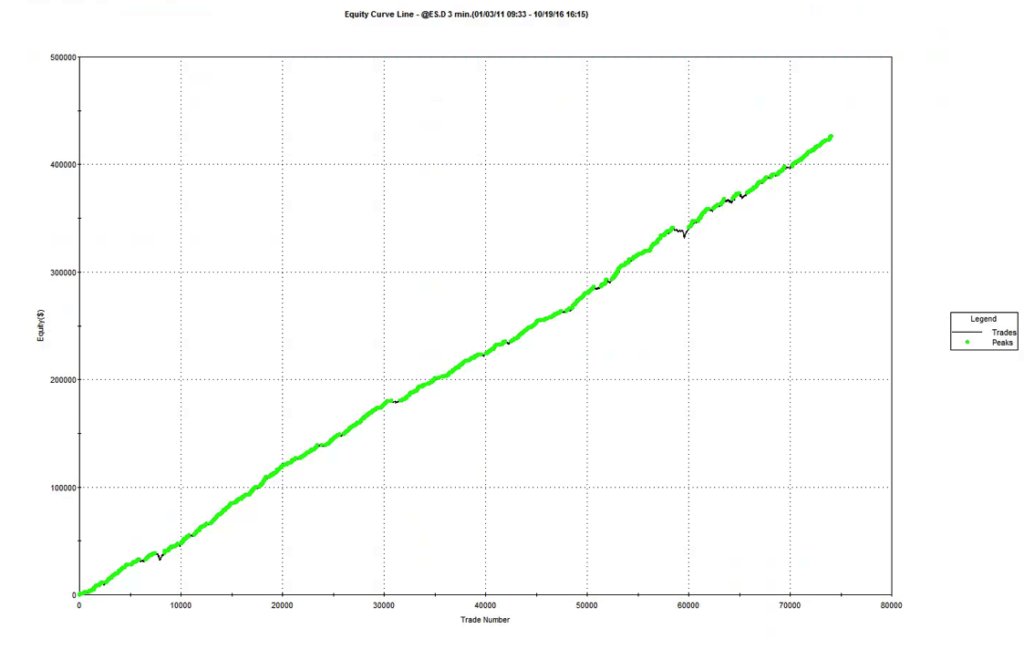

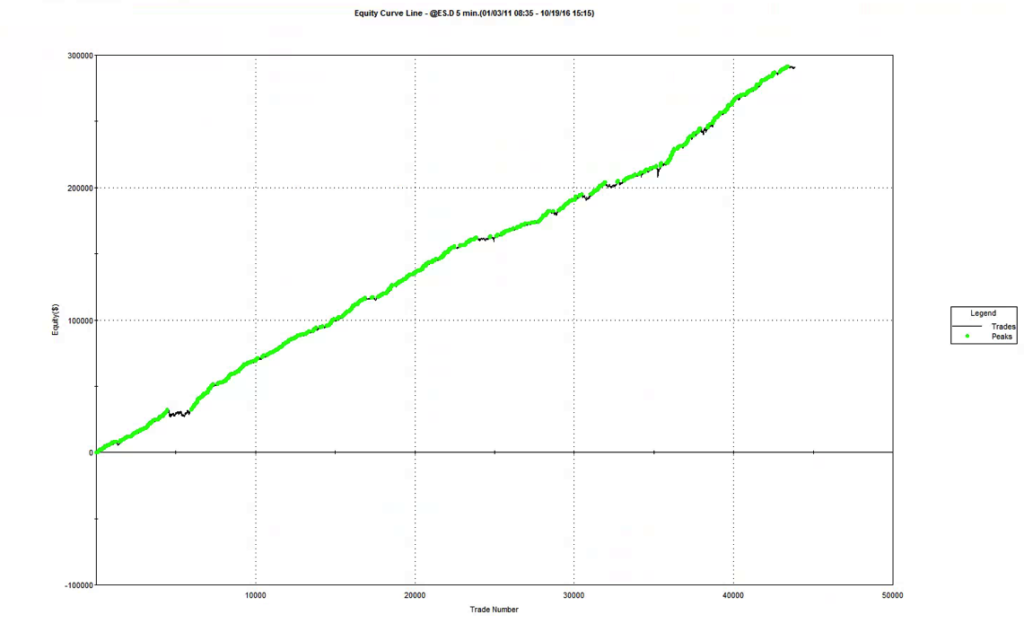

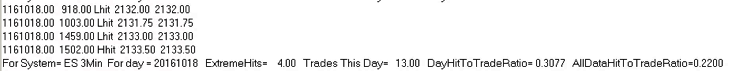

To illustrate the method I will use the following HFT scalping system in the E-Mini S&P500 futures contract. The system trades the E-Mini futures on 3 minute bars, with an average hold time of 15 minutes. The average trade is very low – around $6, net of commissions of $8 prt. But the strategy appears to be highly profitable ,due to the large number of trades – around 50 to 60 per day, on average.

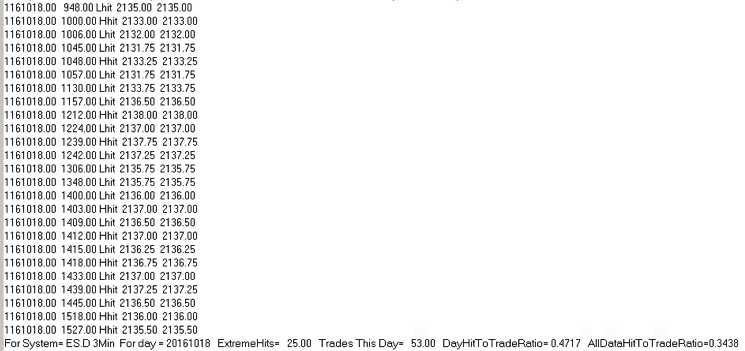

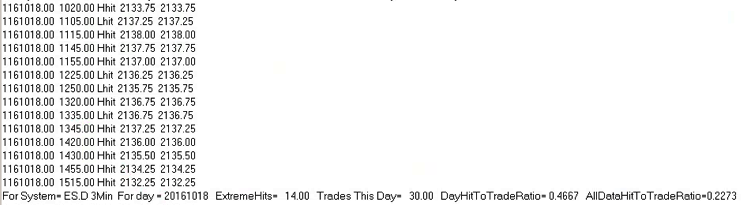

So far so good. But the critical issue is the very large number of extreme hits produced by the strategy. Take the trading activity on 10/18 as an example (see below). Of 53 trades that day, 25 (47%) were extreme hits, occurring at the high or low price of the 3-minute bar in which the trade took place.

Overall, the strategy extreme hit rate runs at 34%, which is extremely high. In reality, perhaps only 1/4 or 1/3 of these orders will actually execute – meaning that remainder, amounting to around 20% of the total number of orders, will fail. A HFT scalping strategy cannot hope to survive such an outcome. Strategy profitability will be decimated by a combination of missed, profitable trades and losses on trades that escalate after an exit order fails to execute.

So what can be done in such a situation?

Manual Override, MIT and Other Interventions

One approach that will not work is to assume naively that some kind of manual oversight will be sufficient to correct the problem. Let’s say the trader runs two versions of the system side by side, one in simulation and the other in production. When a limit order executes on the simulation system, but fails to execute in production, the trader might step in, manually override the system and execute the trade by crossing the spread. In so doing the trader might prevent losses that would have occurred had the trade not been executed, or force the entry into a trade that later turns out to be profitable. Equally, however, the trader might force the exit of a trade that later turns around and moves from loss into profit, or enter a trade that turns out to be a loser. There is no way for the trader to know, ex-ante, which of those scenarios might play out. And the trader will have to face the same decision perhaps as many as twenty times a day. If the trader is really that good at picking winners and cutting losers he should scrap his trading system and trade manually!

An alternative approach would be to have the trading system handle the problem, For example, one could program the system to convert limit orders to market orders if a trade occurs at the limit price (MIT), or after x seconds after the limit price is touched. Again, however, there is no way to know in advance whether such action will produce a positive outcome, or an even worse outcome compared to leaving the limit order in place.

In reality, intervention, whether manual or automated, is unlikely to improve the trading performance of the system. What is certain, however, is that by forcing the entry and exit of trades that occur around the extreme of a price bar, the trader will incur additional costs by crossing the spread. Incurring that cost for perhaps as many as 1/3 of all trades, in a system that is producing, on average less than half a tick per trade, is certain to destroy its profitability.

Successfully Implementing HFT Strategies on a Retail Platform

For many years I assumed that the only solution to the fill rate problem was to implement scalping strategies on HFT infrastructure. One day, I found myself asking the question: what would happen if we slowed the strategy down? Specifically, suppose we took the 3-minute E-Mini strategy and ran it on 5-minute bars?

My first realization was that the relative simplicity of alpha-generation algorithms in HFT strategies is an advantage here. In a low frequency context, the complexity of the alpha extraction process mitigates its ability to generalize to other assets or time-frames. But HFT algorithms are, by and large, simple and generic: what works on 3-minute bars for the E-Mini futures might work on 5-minute bars in E-Minis, or even in SPY. For instance, if the essence of the algorithm is something as simple as: “buy when the price falls by more than x% below its y-bar moving average”, that approach might work on 3-minute, 5-minute, 60-minute, or even daily bars.

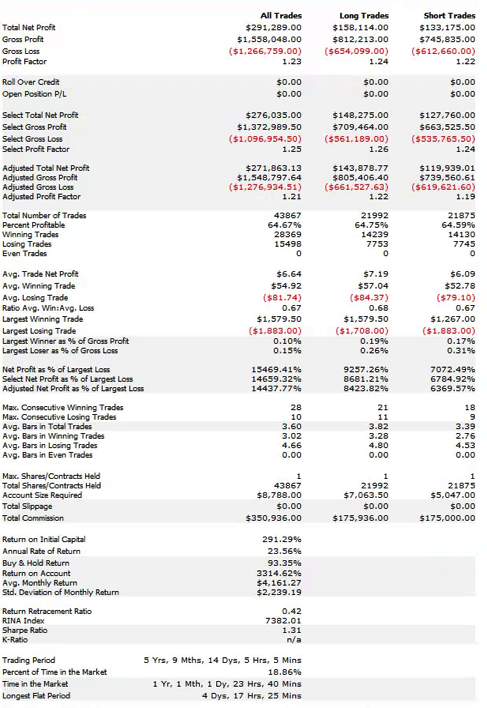

So what happens if we run the E-mini scalping system on 5-minute bars instead of 3-minute bars?

Obviously the overall profitability of the strategy is reduced, in line with the lower number of trades on this slower time-scale. But note that average trade has increased and the strategy remains very profitable overall.

More importantly, the average extreme hit rate has fallen from 34% to 22%.

Hence, not only do we get fewer, slightly more profitable trades, but a much lower proportion of them occur at the extreme of the 5-minute bars. Consequently the fill-rate issue is less critical on this time frame.

Of course, one can continue this process. What about 10-minute bars, or 30-minute bars? What one tends to find from such experiments is that there is a time frame that optimizes the trade-off between strategy profitability and fill rate dependency.

However, there is another important factor we need to elucidate. If you examine the trading record from the system you will see substantial variation in the extreme hit rate from day to day (for example, it is as high as 46% on 10/18, compared to the overall average of 22%). In fact, there are significant variations in the extreme hit rate during the course of each trading day, with rates rising during slower market intervals such as from 12 to 2pm. The important realization that eventually occurred to me is that, of course, what matters is not clock time (or “wall time” in HFT parlance) but trade time: i.e. the rate at which trades occur.

Wall Time vs Trade Time

What we need to do is reconfigure our chart to show bars comprising a specified number of trades, rather than a specific number of minutes. In this scheme, we do not care whether the elapsed time in a given bar is 3-minutes, 5-minutes or any other time interval: all we require is that the bar comprises the same amount of trading activity as any other bar. During high volume periods, such as around market open or close, trade time bars will be shorter, comprising perhaps just a few seconds. During slower periods in the middle of the day, it will take much longer for the same number of trades to execute. But each bar represents the same level of trading activity, regardless of how long a period it may encompass.

How do you decide how may trades per bar you want in the chart?

As a rule of thumb, a strategy will tolerate an extreme hit rate of between 15% and 25%, depending on the daily trade rate. Suppose that in its original implementation the strategy has an unacceptably high hit rate of 50%. And let’s say for illustrative purposes that each time-bar produces an average of 1, 000 contracts. Since volatility scales approximately with the square root of time, if we want to reduce the extreme hit rate by a factor of 2, i.e. from 50% to 25%, we need to increase the average number of trades per bar by a factor of 2^2, i.e. 4. So in this illustration we would need volume bars comprising 4,000 contracts per bar. Of course, this is just a rule of thumb – in practice one would want to implement the strategy of a variety of volume bar sizes in a range from perhaps 3,000 to 6,000 contracts per bar, and evaluate the trade-off between performance and fill rate in each case.

Using this approach, we arrive at a volume bar configuration for the E-Mini scalping strategy of 20,000 contracts per bar. On this “time”-frame, trading activity is reduced to around 20-25 trades per day, but with higher win rate and average trade size. More importantly, the extreme hit rate runs at a much lower average of 22%, which means that the trader has to worry about maybe only 4 or 5 trades per day that occur at the extreme of the volume bar. In this scenario manual intervention is likely to have a much less deleterious effect on trading performance and the strategy is probably viable, even on a retail trading platform.

(Note: the results below summarize the strategy performance only over the last six months, the time period for which volume bars are available).

Concluding Remarks

We have seen that is it feasible in principle to implement a HFT scalping strategy on a retail platform by slowing it down, i.e. by implementing the strategy on bars of lower frequency. The simplicity of many HFT alpha generation algorithms often makes them robust to generalization across time frames (and sometimes even across assets). An even better approach is to use volume bars, or trade-time, to implement the strategy. You can estimate the appropriate bar size using the square root of time rule to adjust the bar volume to produce the requisite fill rate. An extreme hit rate if up to 25% may be acceptable, depending on the daily trade rate, although a hit rate in the range of 10% to 15% would typically be ideal.

Finally, a word about data. While necessary compromises can be made with regard to the trading platform and connectivity, the same is not true for market data, which must be of the highest quality, both in terms of timeliness and completeness. The reason is self evident, especially if one is attempting to implement a strategy in trade time, where the integrity and latency of market data is crucial. In this context, using the data feed from, say, Interactive Brokers, for example, simply will not do – data delivered in 500ms packets in entirely unsuited to the task. The trader must seek to use the highest available market data feed that he can reasonably afford.

That caveat aside, one can conclude that it is certainly feasible to implement high volume scalping strategies, even on a retail trading platform, providing sufficient care is taken with the modeling and implementation of the system.

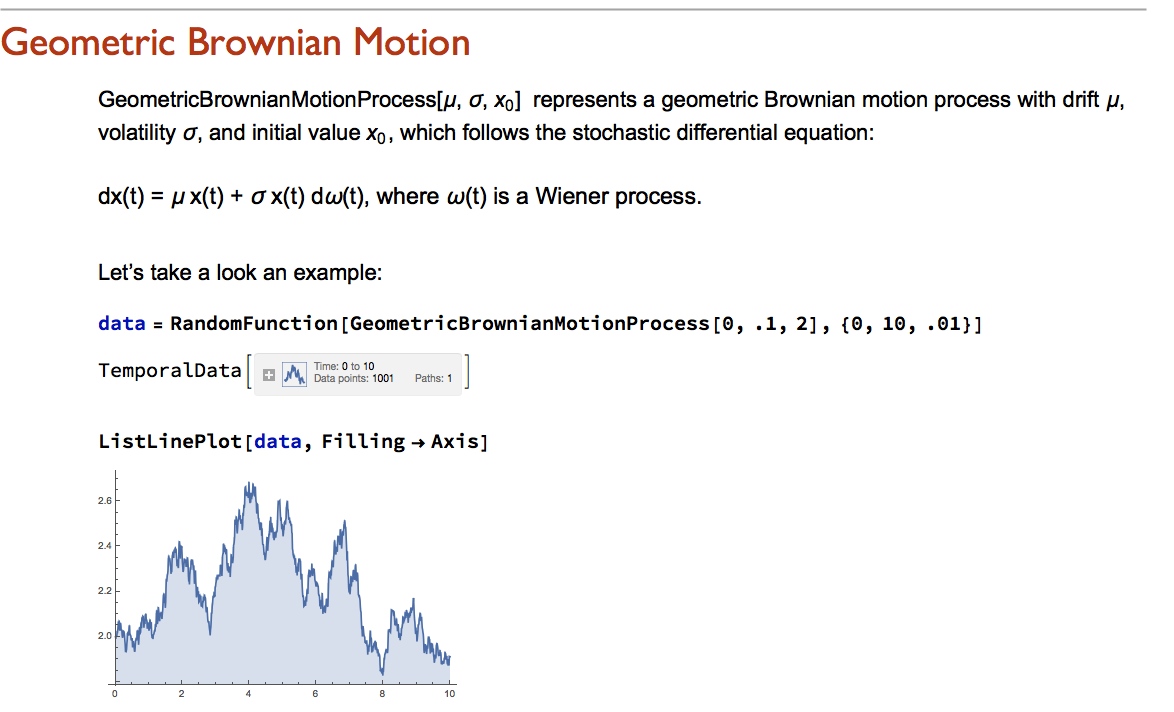

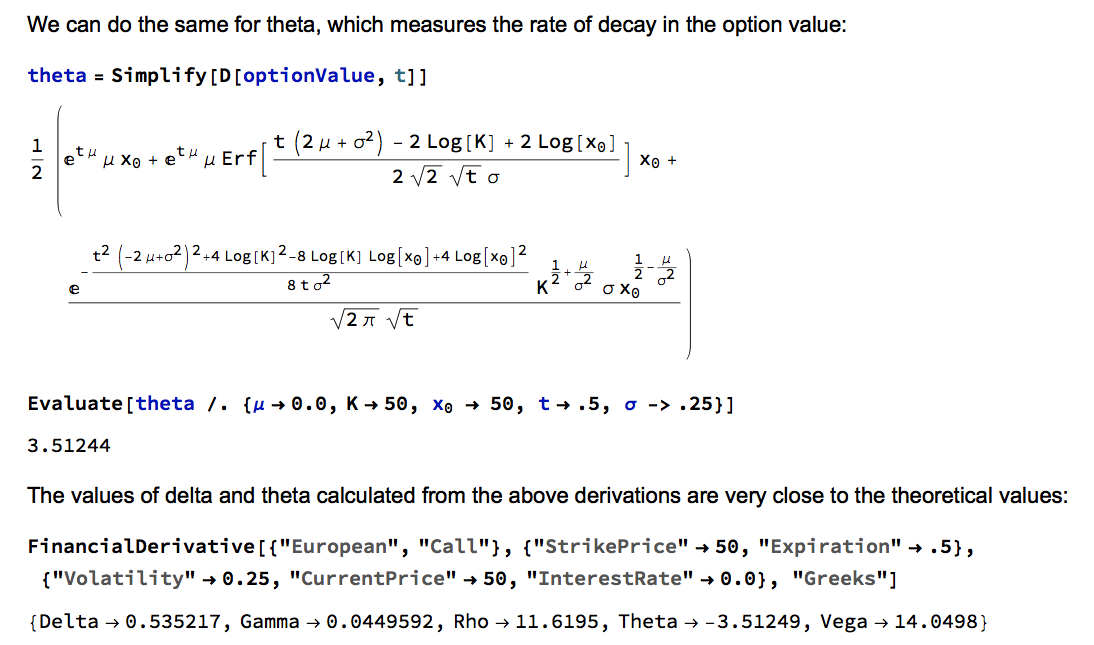

Stochastic Calculus in Mathematica

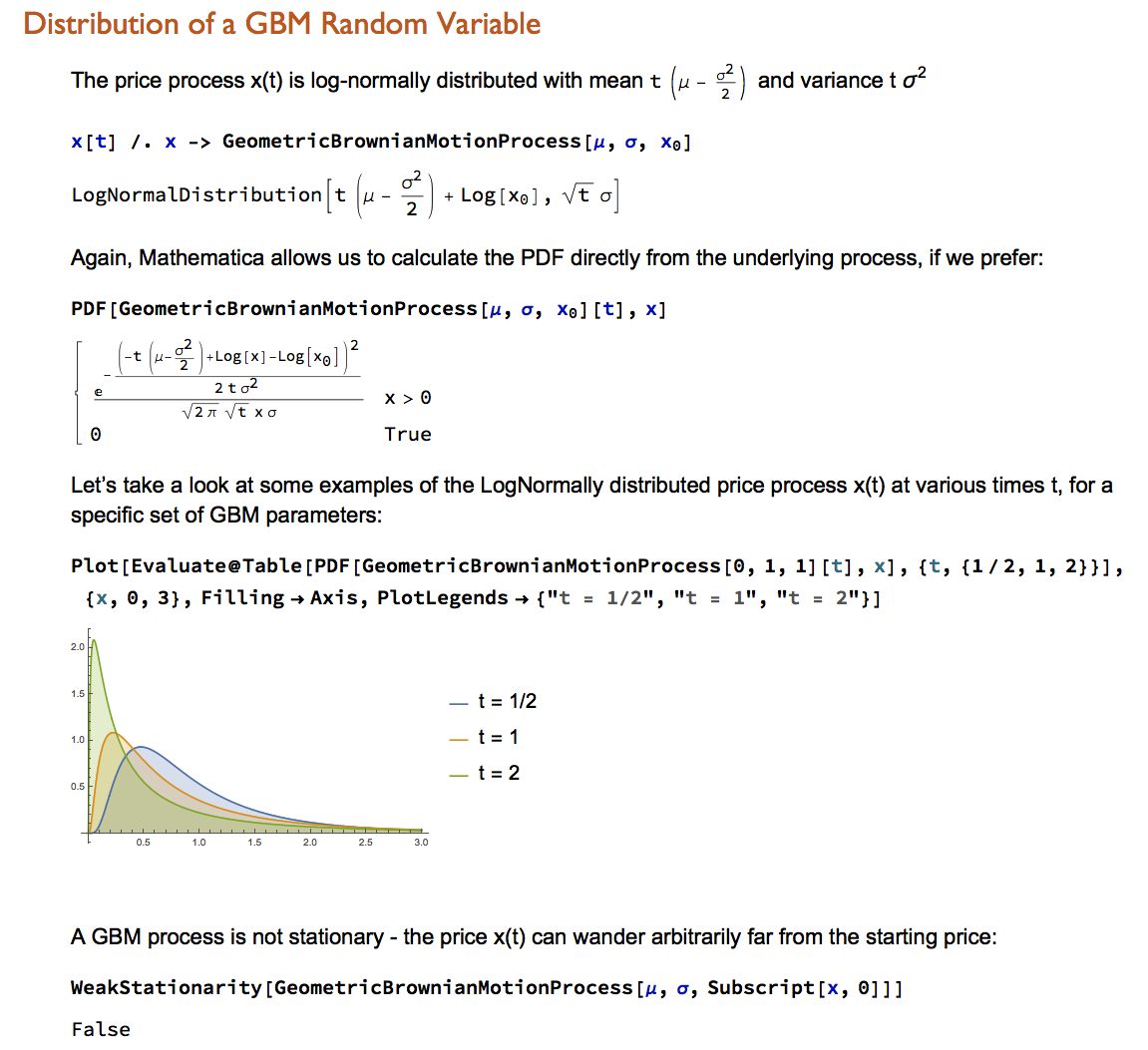

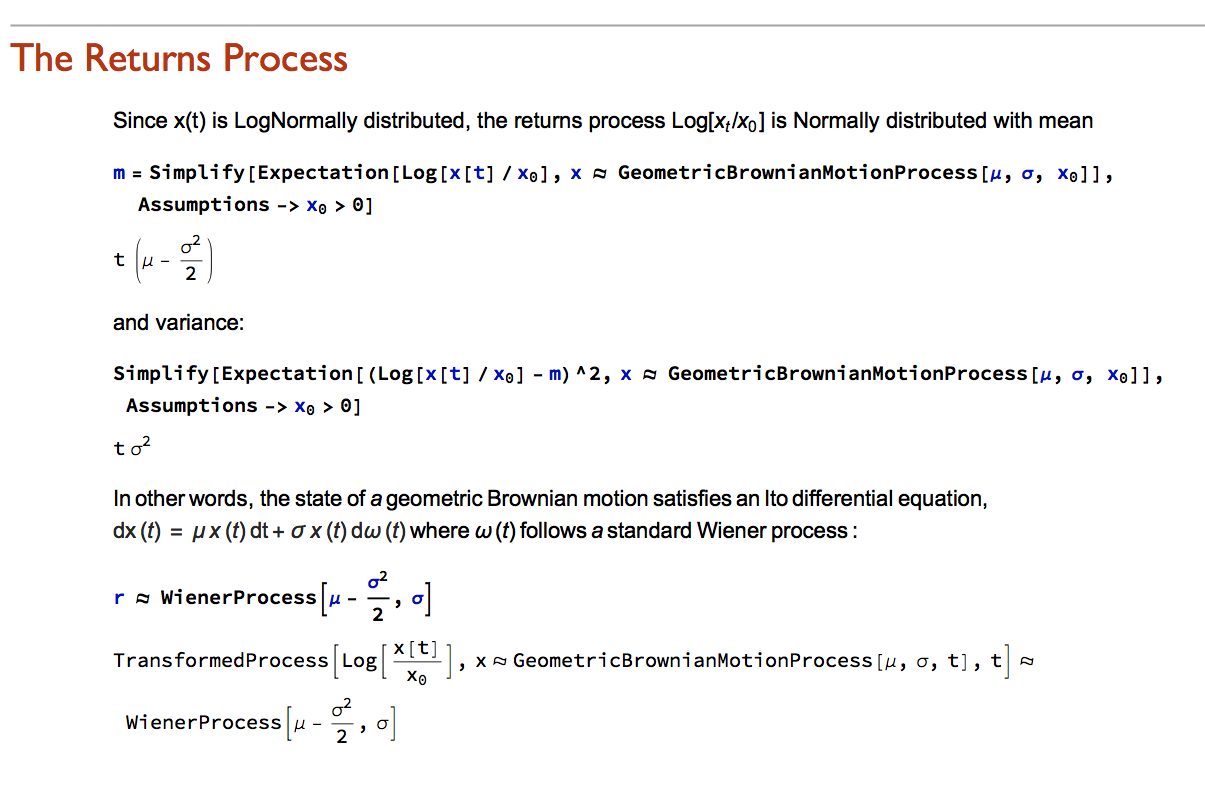

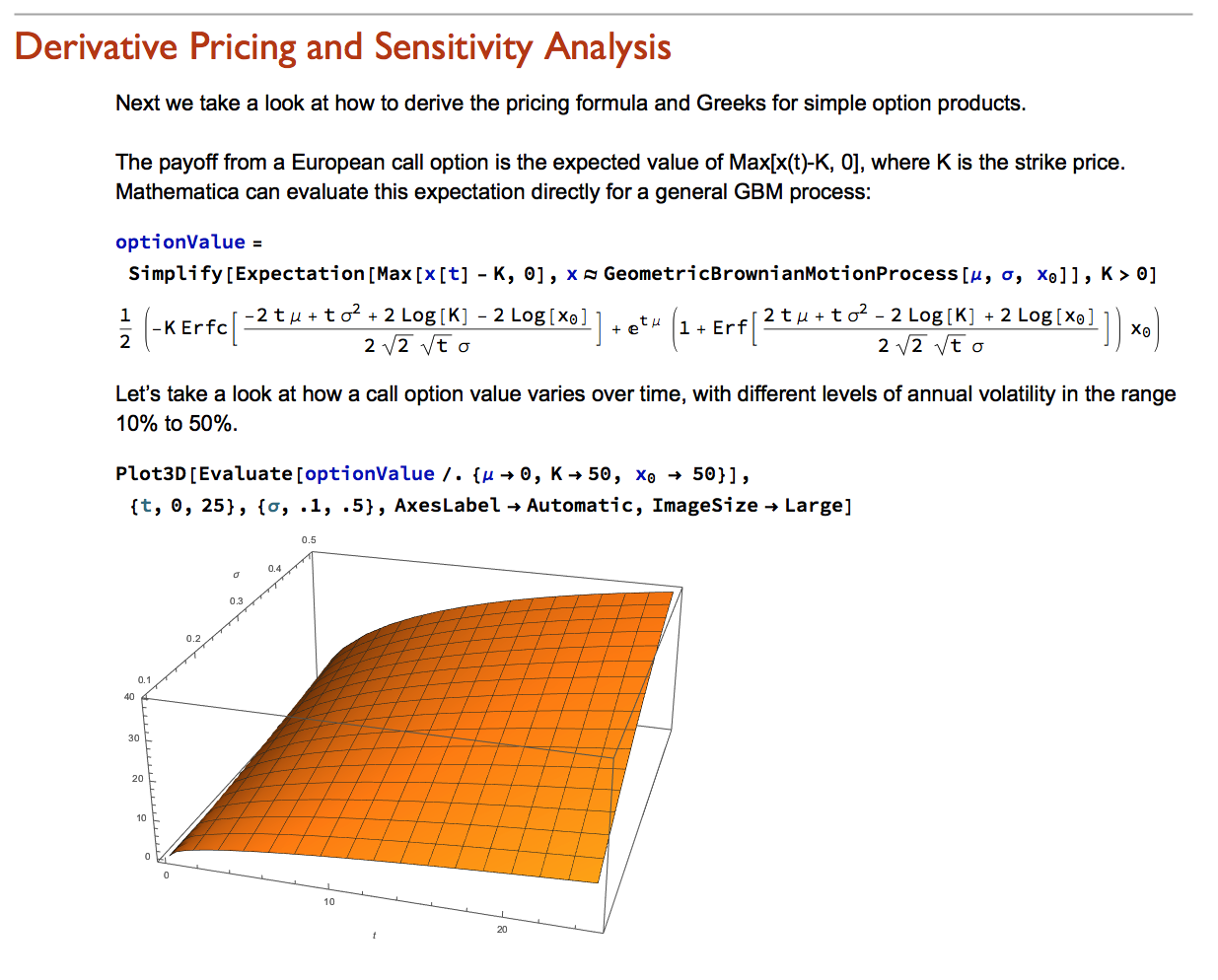

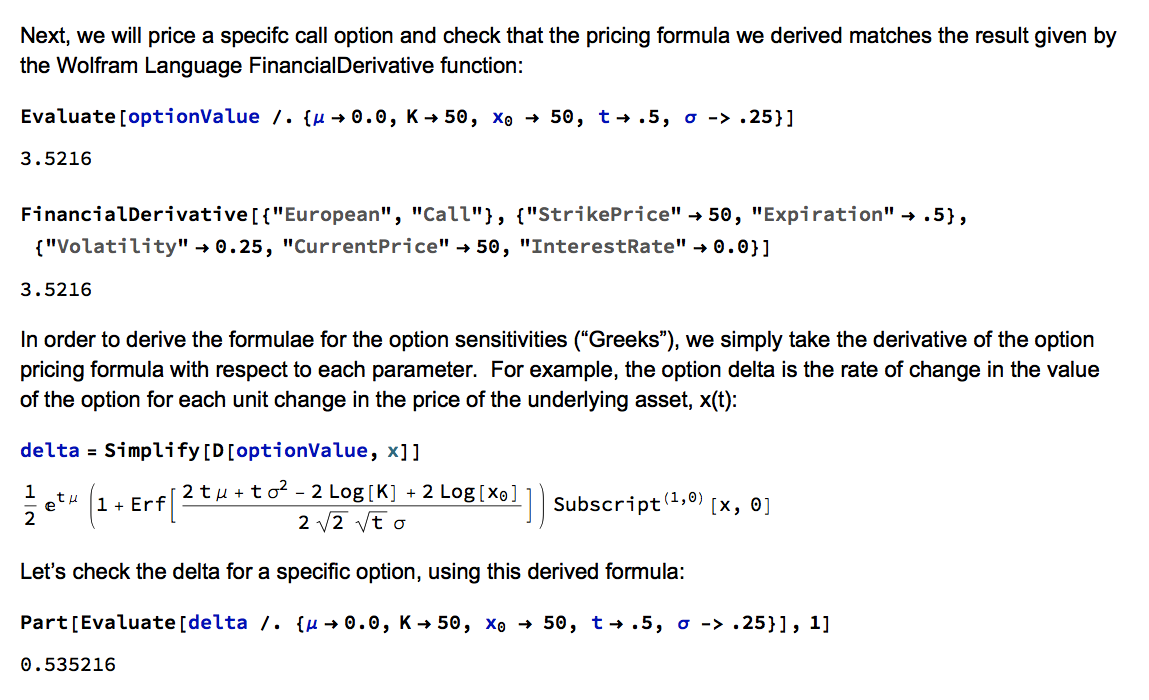

Wolfram Research introduced random processes in version 9 of Mathematica and for the first time users were able to tackle more complex modeling challenges such as those arising in stochastic calculus. The software’s capabilities in this area have grown and matured over the last two versions to a point where it is now feasible to teach stochastic calculus and the fundamentals of financial engineering entirely within the framework of the Wolfram Language. In this post we take a lightening tour of some of the software’s core capabilities and give some examples of how it can be used to create the building blocks required for a complete exposition of the theory behind modern finance.

Conclusion

Financial Engineering has long been a staple application of Mathematica, an area in which is capabilities in symbolic logic stand out. But earlier versions of the software lacked the ability to work with Ito calculus and model stochastic processes, leaving the user to fill in the gaps by other means. All that changed in version 9 and it is now possible to provide the complete framework of modern financial theory within the context of the Wolfram Language.

The advantages of this approach are considerable. The capabilities of the language make it easy to provide interactive examples to illustrate theoretical concepts and develop the student’s understanding of them through experimentation. Furthermore, the student is not limited merely to learning and applying complex formulae for derivative pricing and risk, but can fairly easily derive the results for themselves. As a consequence, a course in stochastic calculus taught using Mathematica can be broader in scope and go deeper into the theory than is typically the case, while at the same time reinforcing understanding and learning by practical example and experimentation.

Applications of Graph Theory In Finance

Analyzing Big Data

Very large datasets – comprising voluminous numbers of symbols – present challenges for the analyst, not least of which is the difficulty of visualizing relationships between the individual component assets. Absent the visual clues that are often highlighted by graphical images, it is easy for the analyst to overlook important changes in relationships. One means of tackling the problem is with the use of graph theory.

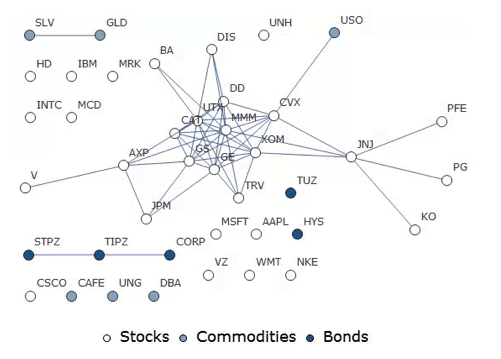

DOW 30 Index Member Stocks Correlation Graph

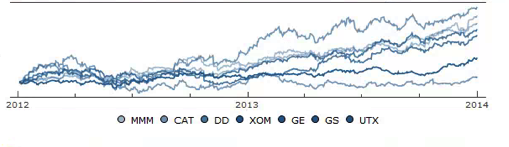

In this example I have selected a universe of the Dow 30 stocks, together with a sample of commodities and bonds and compiled a database of daily returns over the period from Jan 2012 to Dec 2013. If we want to look at how the assets are correlated, one way is to created an adjacency graph that maps the interrelations between assets that are correlated at some specified level (0.5 of higher, in this illustration).

Obviously the choice of correlation threshold is somewhat arbitrary, and it is easy to evaluate the results dynamically, across a wide range of different threshold parameters, say in the range from 0.3 to 0.75:

The choice of parameter (and time frame) may be dependent on the purpose of the analysis: to construct a portfolio we might select a lower threshold value; but if the purpose is to identify pairs for possible statistical arbitrage strategies, one will typically be looking for much higher levels of correlation.

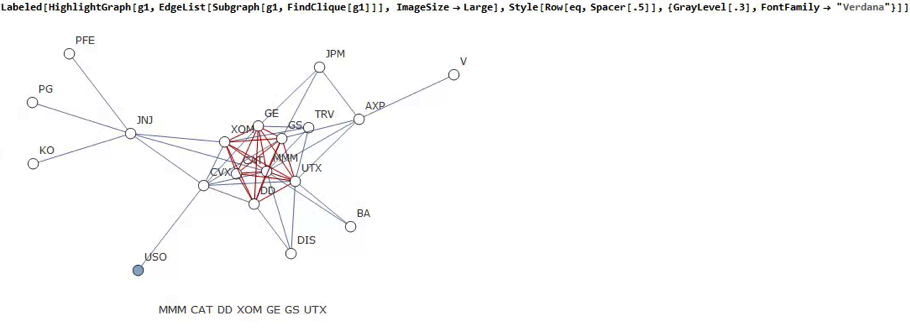

Correlated Cliques

Reverting to the original graph, there is a core group of highly inter-correlated stocks that we can easily identify more clearly using the Mathematica function FindClique to specify graph nodes that have multiple connections:

We might, for example, explore the relative performance of members of this sub-group over time and perhaps investigate the question as to whether relative out-performance or under-performance is likely to persist, or, given the correlation characteristics of this group, reverse over time to give a mean-reversion effect.

Constructing a Replicating Portfolio

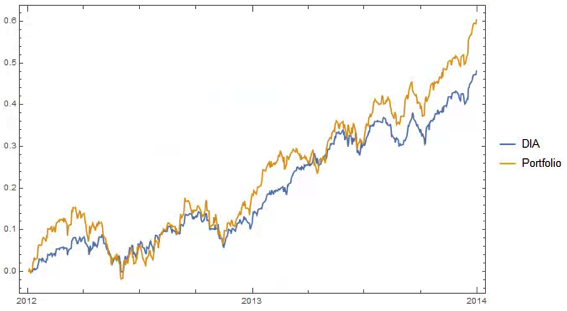

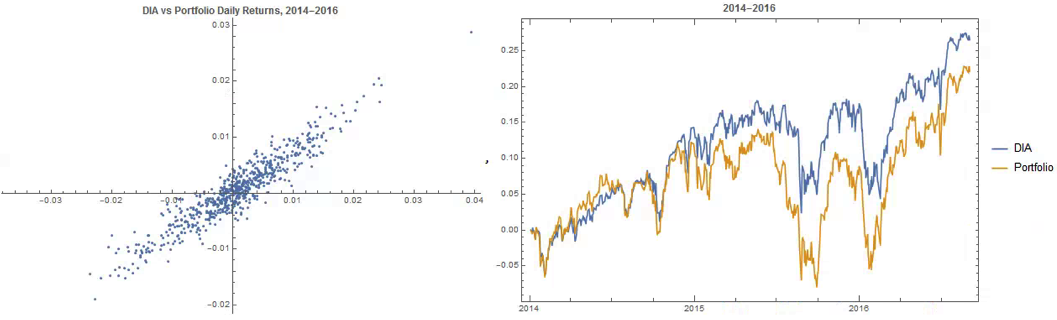

An obvious application might be to construct a replicating portfolio comprising this equally-weighted sub-group of stocks, and explore how well it tracks the Dow index over time (here I am using the DIA ETF as a proxy for the index, for the sake of convenience):

The correlation between the Dow index (DIA ETF) and the portfolio remains strong (around 0.91) throughout the out-of-sample period from 2014-2016, although the performance of the portfolio is distinctly weaker than that of the index ETF after the early part of 2014:

Constructing Robust Portfolios

Another application might be to construct robust portfolios of lower-correlated assets. Here for example we use the graph to identify independent vertices that have very few correlated relationships (designated using the star symbol in the graph below). We can then create an equally weighted portfolio comprising the assets with the lowest correlations and compare its performance against that of the Dow Index.

The new portfolio underperforms the index during 2014, but with lower volatility and average drawdown.

Conclusion – Graph Theory has Applications in Portfolio Constructions and Index Replication

Graph theory clearly has a great many potential applications in finance. It is especially useful as a means of providing a graphical summary of data sets involving a large number of complex interrelationships, which is at the heart of portfolio theory and index replication. Another useful application would be to identify and evaluate correlation and cointegration relationships between pairs or small portfolios of stocks, as they evolve over time, in the context of statistical arbitrage.

High Frequency Futures Scalping Strategies Update

Metal Logic

Precious metals have been in free-fall for several years, as a consequence of the Fed’s actions to stimulate the economy that have also had the effect of goosing the equity and fixed income markets. All that changed towards the end of 2015, as the Fed moved to a tightening posture. So far, 2016 has been a banner year for metal, with spot prices for platinum, gold and silver up 26%, 28% and 44% respectively.

So what are the prospects for metals through the end of the year? We take a shot at predicting the outcome, from a quantitative perspective.

Source: Wolfram Alpha. Spot silver prices are scaled x100

Metals as Correlated Processes

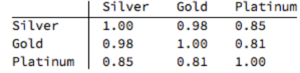

One of the key characteristics of metals is the very high levels of price-correlation between them. Over the period under investigation, Jan 2012 to Aug 2016, the estimated correlation coefficients are as follows:

A plot of the join density of spot gold and silver prices indicates low- and high-price regimes in which the metals display similar levels of linear correlation.

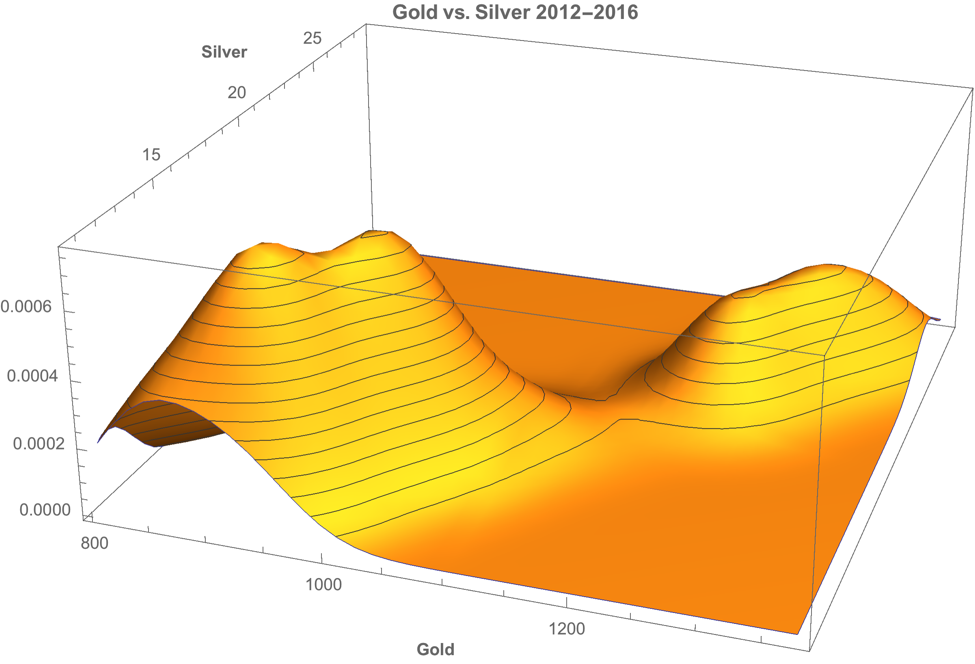

Simple Metal Trading Models

Levels of correlation that are consistently as high as this over extended periods of time are fairly unusual in financial markets and this presents a potential trading opportunity. One common approach is to use the ratios of metal prices as a trading signal. However, taking the ratio of gold to silver spot prices as an example, a plot of the series demonstrates that it is highly unstable and susceptible to long term trends.

A more formal statistical test fails to reject the null hypothesis of a unit root. In simple terms, this means we cannot reliably distinguish between the gold/silver price ratio and a random walk.

Along similar lines, we might consider the difference in log prices of the series. If this proved to be stationary then the log-price series would be cointegrated order 1 and we could build a standard pairs trading model to buy or sell the spread when prices become too far unaligned. However, we find once again that the log-price difference can wander arbitrarily far from its mean, and we are unable to reject the null hypothesis that the series contains a unit root.

Linear Models

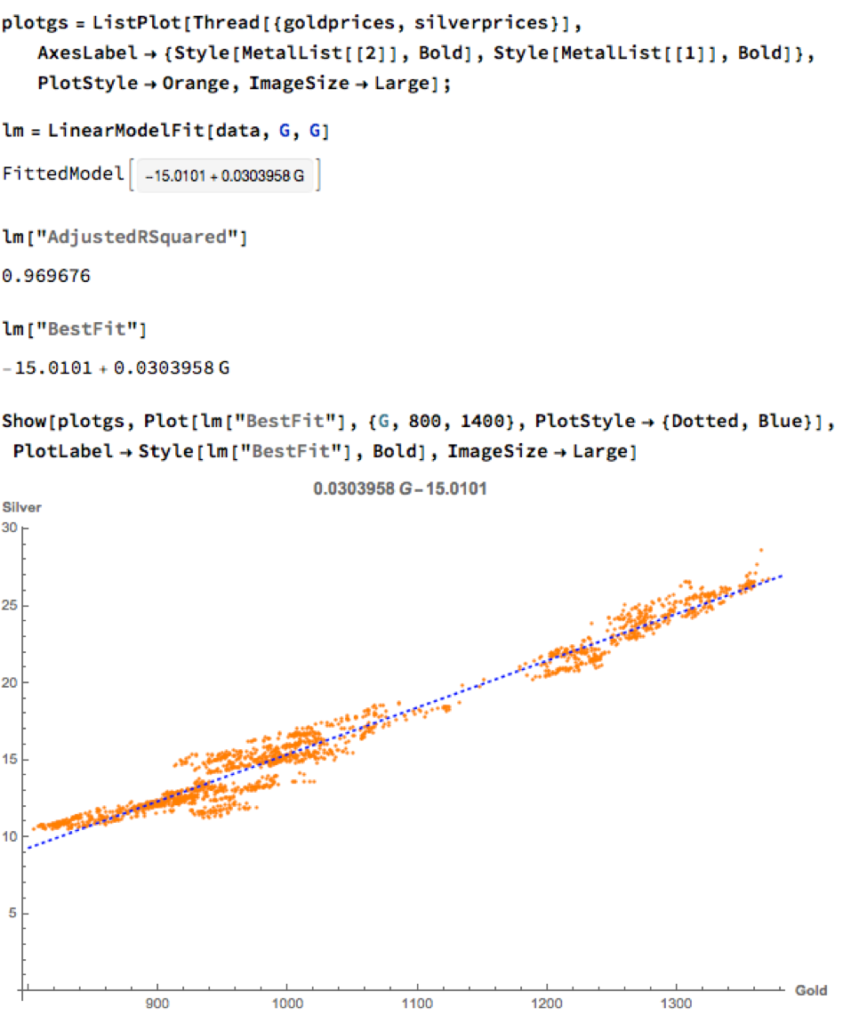

We can hope to do better with a standard linear model, regressing spot silver prices against spot gold prices. The fit of the best linear model is very good, with an R-sq of over 96%:

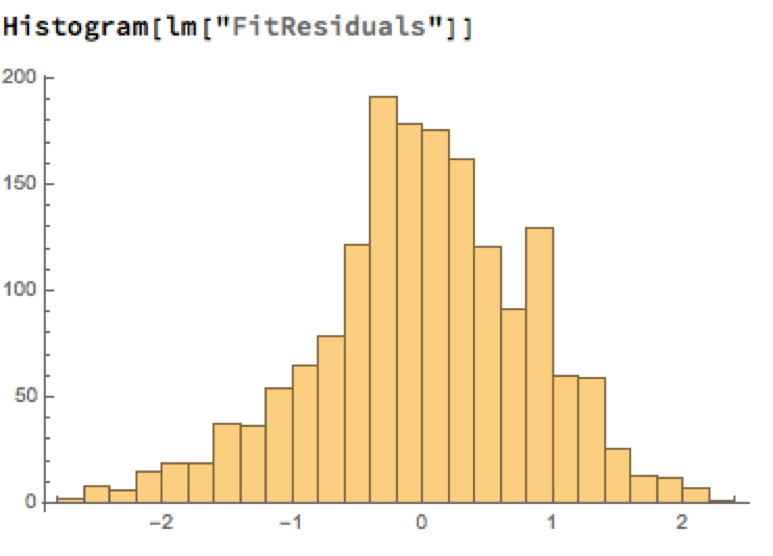

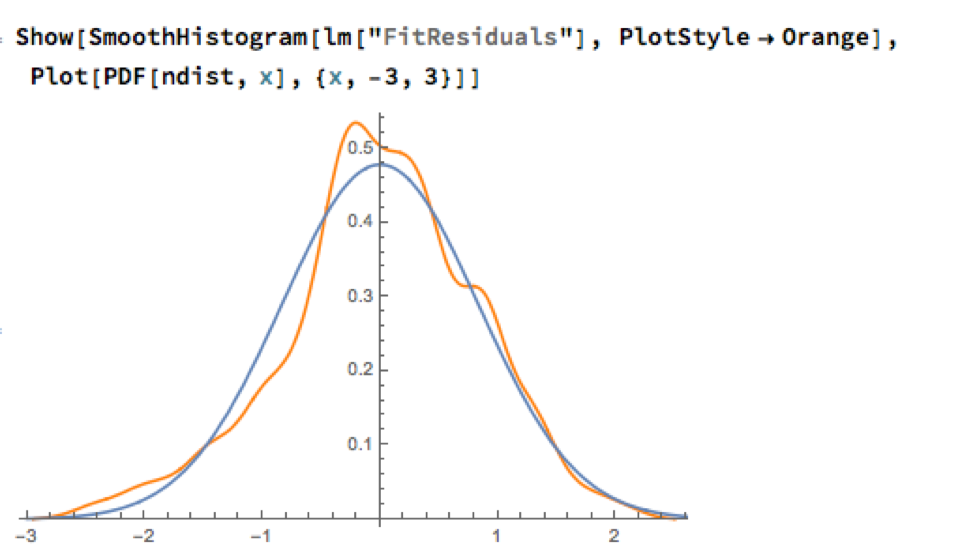

A trader might look to exploit the correlation relationship by selling silver when its market price is greater than the value estimated by the model (and buying when the model price exceeds the market price). Typically the spread is bought or sold when the log-price differential exceeds a threshold level that is set at twice the standard deviation of the price-difference series. The threshold levels derive from the assumption of Normality, which in fact does not apply here, as we can see from an examination of the residuals of the linear model:

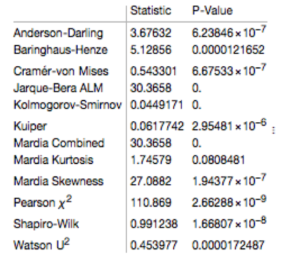

Given the evident lack of fit, especially in the left tail of the distribution, it is unsurprising that all of the formal statistical tests for Normality easily reject the null hypothesis:

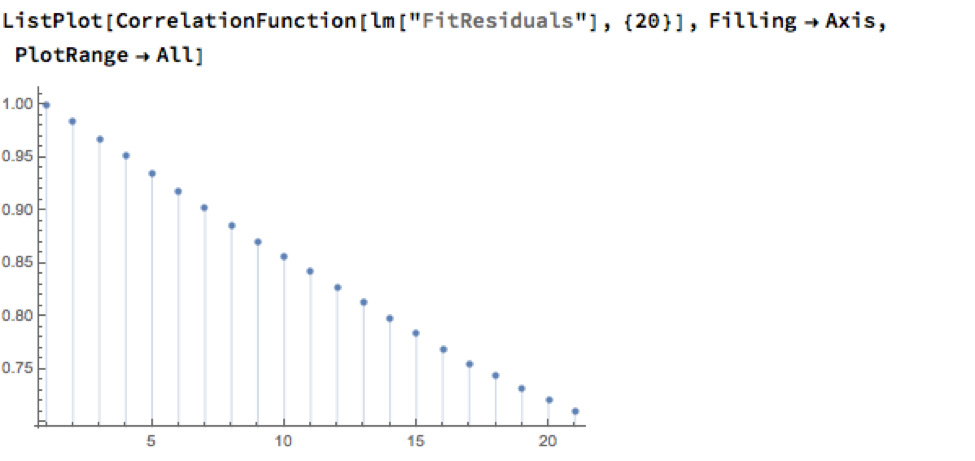

However, Normality, or the lack of it, is not the issue here: one could just as easily set the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles of the empirical distribution as trade entry points. The real problem with the linear model is that it fails to take into account the time dependency in the price series. An examination of the residual autocorrelations reveals significant patterning, indicating that the model tends to under-or over-estimate the spot price of silver for long periods of time:

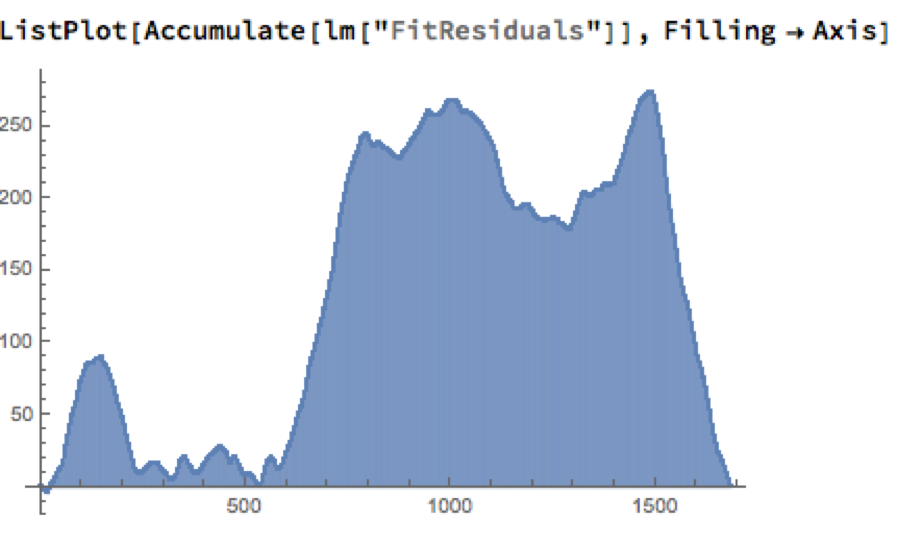

As the following chart shows, the cumulative difference between model and market prices can become very large indeed. A trader risks going bust waiting for the market to revert to model prices.

How does one remedy this? The shortcoming of the simple linear model is that, while it captures the interdependency between the price series very well, it fails to factor in the time dependency of the series. What is required is a model that will account for both features.

Multivariate Vector Autoregression Model

Rather than modeling the metal prices individually, or in pairs, we instead adopt a multivariate vector autoregression approach, modeling all three spot price processes together. The essence of the idea is that spot prices in each metal may be influenced, not only by historical values of the series, but also potentially by current and lagged prices of the other two metals.

Before proceeding we divide the data into two parts: an in-sample data set comprising data from 2012 to the end of 2015 and an out-of-sample period running from Jan-Aug 2016, which we use for model testing purposes. In what follows, I make the simplifying assumption that a vector autoregressive moving average process of order (1, 1) will suffice for modeling purposes, although in practice one would go through a procedure to test a wide spectrum of possible models incorporating moving average and autoregressive terms of varying dimensions.

In any event, our simplified VAR model is estimated as follows:

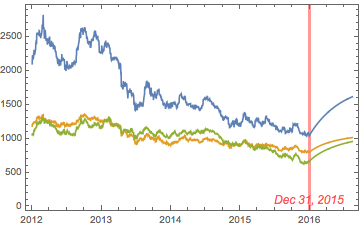

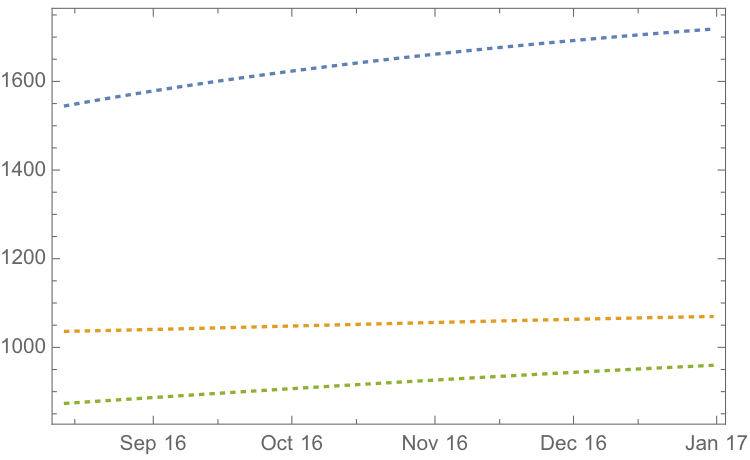

The chart below combines the actual, in-sample data from 2012-2015, together with the out-of-sample forecasts for each spot metal from January 2016.

It is clear that the model projects a recovery in spot metal prices from the end of 2015. How did the forecasts turn out? In the chart below we compare the actual spot prices with the model forecasts, over the period from Jan to Aug 2016.

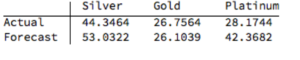

The actual and forecast percentage change in the spot metal prices over the out-of-sample period are as follows:

The VAR model does a good job of forecasting the strong upward trend in metal prices over the first eight months of 2016. It performs exceptionally well in its forecast of gold prices, although its forecasts for silver and platinum are somewhat over-optimistic. Nevertheless, investors would have made money taking a long position in any of the metals on the basis of the model projections.

Relative Value Trade

Another way to apply the model would be to implement a relative value trade, based on the model’s forecast that silver would outperform gold and platinum. Indeed, despite the model’s forecast of silver prices turning out to be over-optimistic, a relative value trade in silver vs. gold or platinum would have performed well: silver gained 44% in the period form Jan-Aug 2016, compared to only 26% for gold and 28% for platinum. A relative value trade entailing a purchase of silver and simultaneous sale of gold or platinum would have produced a gross return of 17% and 15% respectively.

A second relative value trade indicated by the model forecasts, buying platinum and selling gold, would have turned out less successfully, producing a gross return of less than 2%. We will examine the reasons for this in the next section.

Forecasts and Trading Opportunities Through 2016

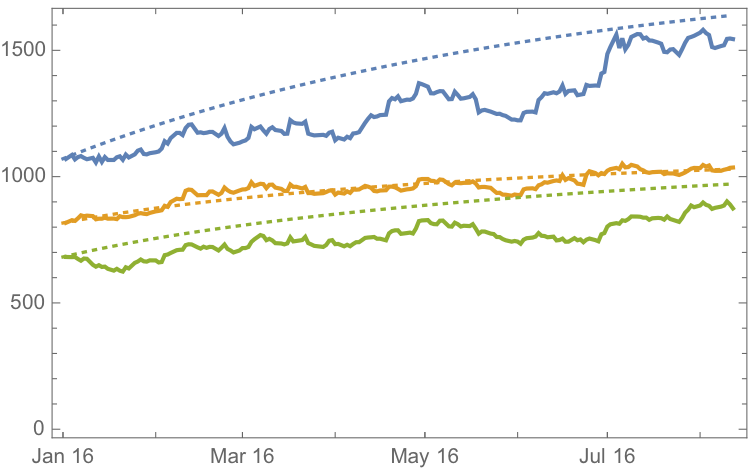

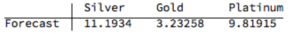

If we re-estimate the VAR model using all of the the available data through mid-Aug 2016 and project metal prices through the end of the year, the outcome is as follows:

While the positive trend in all three metals is forecast to continue, the new model (which incorporates the latest data) anticipates lower percentage rates of appreciation going forward:

Once again, the model predicts higher rates of appreciation for both silver and platinum relative to gold. So investors have the option to take a relative value trade, hedging a long position in silver or platinum with a short position in gold. While the forecasts for all three metals appear reasonable, the projections for platinum strike me as the least plausible.

The reason is that the major applications of platinum are industrial, most often as a catalyst: the metal is used as a catalytic converter in automobiles and in the chemical process of converting naphthas into higher-octane gasolines. Although gold is also used in some industrial applications, its demand is not so driven by industrial uses. Consequently, during periods of sustained economic stability and growth, the price of platinum tends to be as much as twice the price of gold, whereas during periods of economic uncertainty, the price of platinum tends to decrease due to reduced industrial demand, falling below the price of gold. Gold prices are more stable in slow economic times, as gold is considered a safe haven.

This is the most likely explanation of why the gold-platinum relative value trade has not worked out as expected hitherto and is perhaps unlikely to do so in the months ahead, as the slowdown in the global economy continues.

Conclusion

We have shown that simple models of the ratio or differential in the prices of precious metals are unlikely to provide a sound basis for forecasting or trading, due to non-stationarity and/or temporal dependencies in the residuals from such models.

On the other hand, a vector autoregression model that models all three price processes simultaneously, allowing both cross correlations and autocorrelations to be captured, performs extremely well in terms of forecast accuracy in out-of-sample tests over the period from Jan-Aug 2016.

Looking ahead over the remainder of the year, our updated VAR model predicts a continuation of the price appreciation, albeit at a slower rate, with silver and platinum expected to continue outpacing gold. There are reasons to doubt whether the appreciation of platinum relative to gold will materialize, however, due to falling industrial demand as the global economy cools.

Dynamic Time Warping

Machine Learning Trading Systems

The SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) is one of the widely traded ETF products on the market, with around $200Bn in assets and average turnover of just under 200M shares daily. So the likelihood of being able to develop a money-making trading system using publicly available information might appear to be slim-to-none. So, to give ourselves a fighting chance, we will focus on an attempt to predict the overnight movement in SPY, using data from the prior day’s session.

In addition to the open/high/low and close prices of the preceding day session, we have selected a number of other plausible variables to build out the feature vector we are going to use in our machine learning model:

- The daily volume

- The previous day’s closing price

- The 200-day, 50-day and 10-day moving averages of the closing price

- The 252-day high and low prices of the SPY series

We will attempt to build a model that forecasts the overnight return in the ETF, i.e. [O(t+1)-C(t)] / C(t)

In this exercise we use daily data from the beginning of the SPY series up until the end of 2014 to build the model, which we will then test on out-of-sample data running from Jan 2015-Aug 2016. In a high frequency context a considerable amount of time would be spent evaluating, cleaning and normalizing the data. Here we face far fewer problems of that kind. Typically one would standardized the input data to equalize the influence of variables that may be measured on scales of very different orders of magnitude. But in this example all of the input variables, with the exception of volume, are measured on the same scale and so standardization is arguably unnecessary.

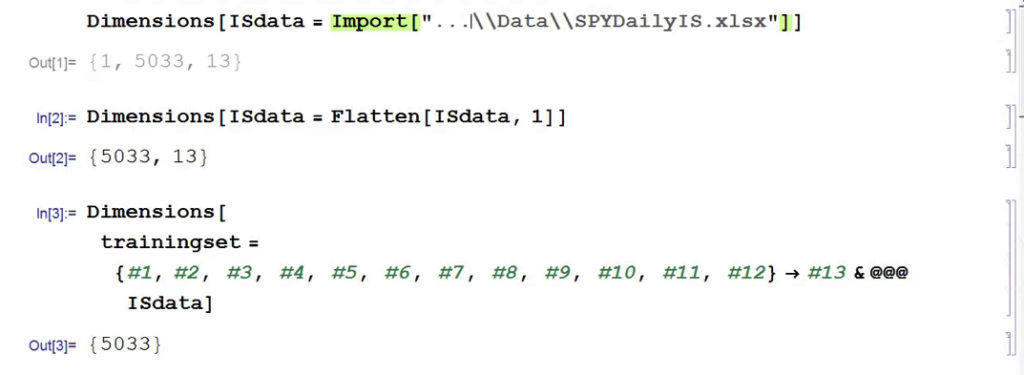

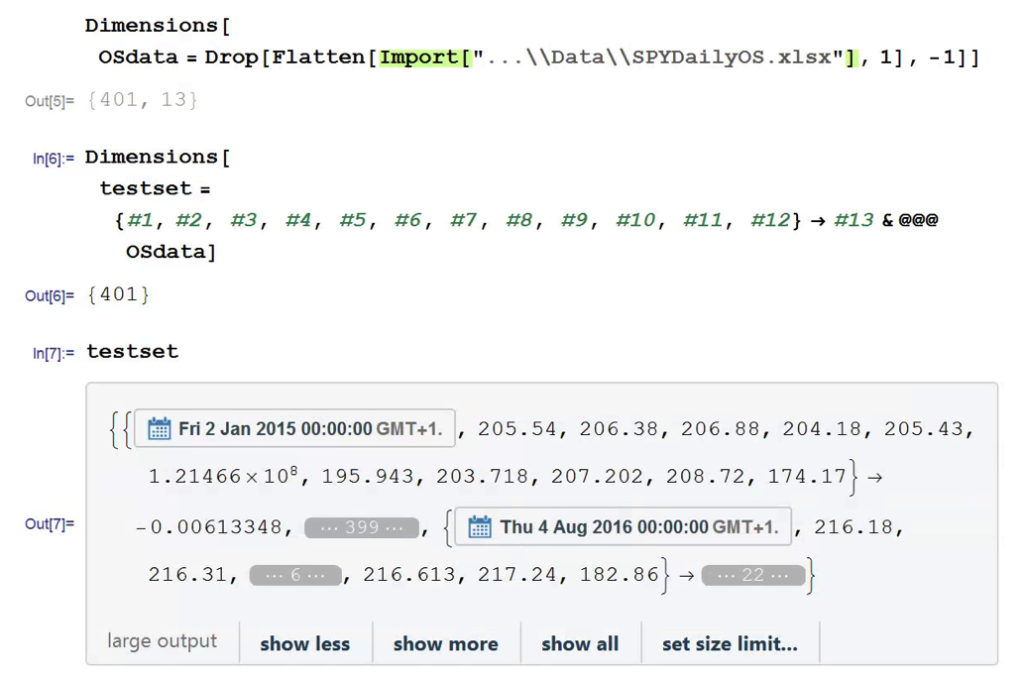

First, the in-sample data is loaded and used to create a training set of rules that map the feature vector to the variable of interest, the overnight return:

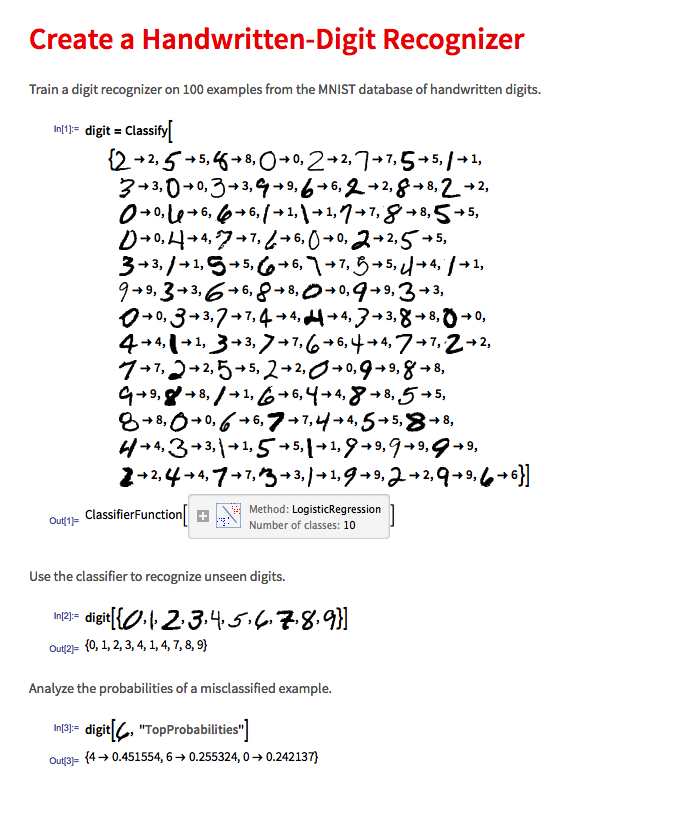

In Mathematica 10 Wolfram introduced a suite of machine learning algorithms that include regression, nearest neighbor, neural networks and random forests, together with functionality to evaluate and select the best performing machine learning technique. These facilities make it very straightfoward to create a classifier or prediction model using machine learning algorithms, such as this handwriting recognition example:

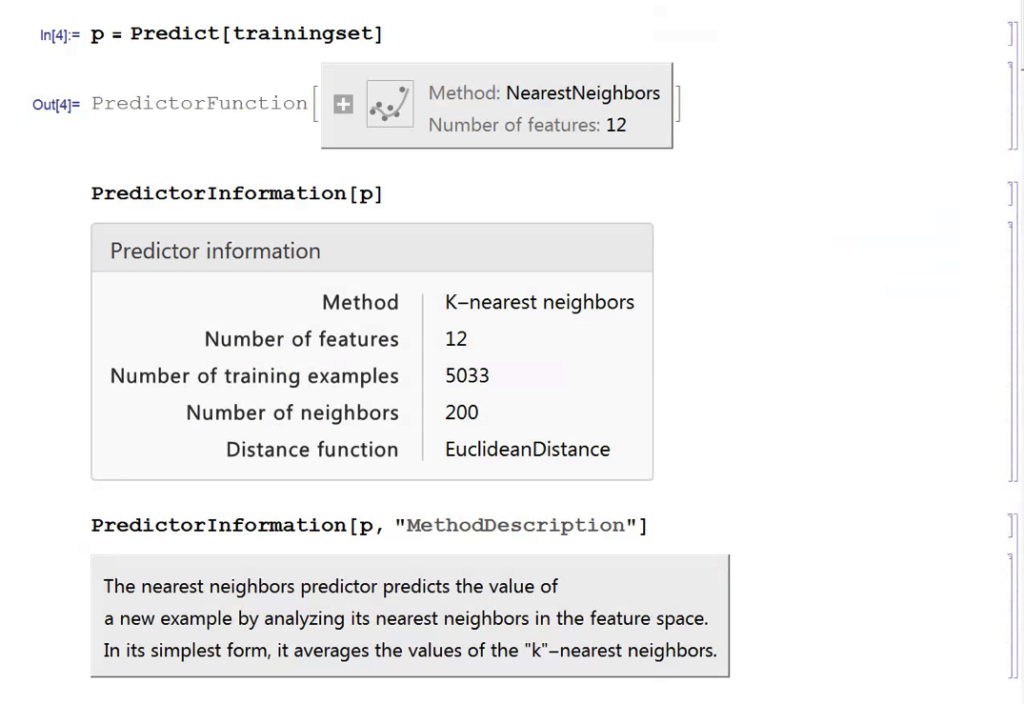

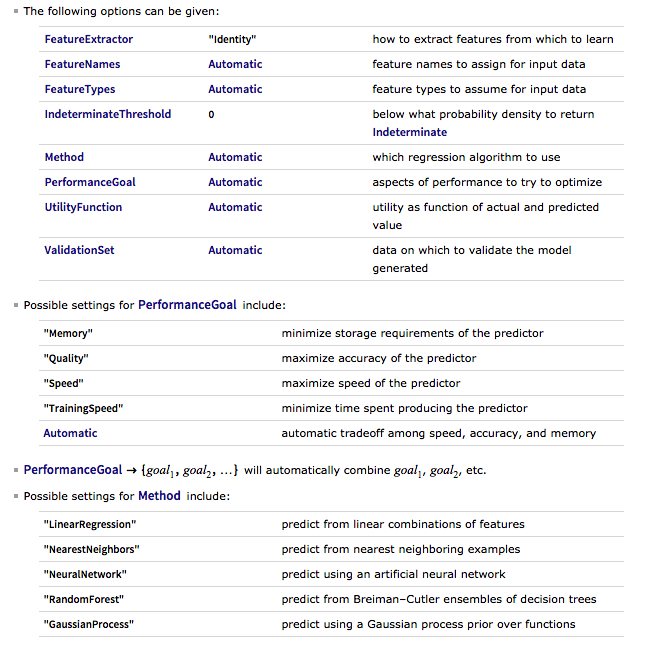

We create a predictive model on the SPY trainingset, allowing Mathematica to pick the best machine learning algorithm:

There are a number of options for the Predict function that can be used to control the feature selection, algorithm type, performance type and goal, rather than simply accepting the defaults, as we have done here:

Having built our machine learning model, we load the out-of-sample data from Jan 2015 to Aug 2016, and create a test set:

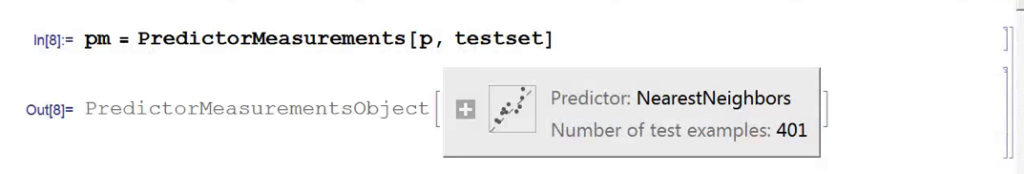

We next create a PredictionMeasurement object, using the Nearest Neighbor model , that can be used for further analysis:

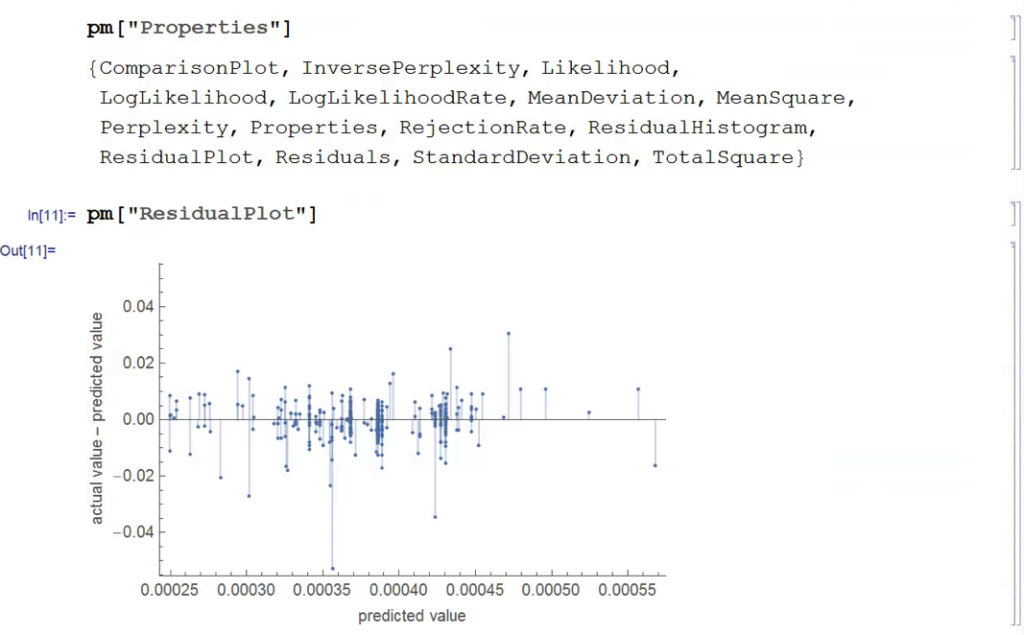

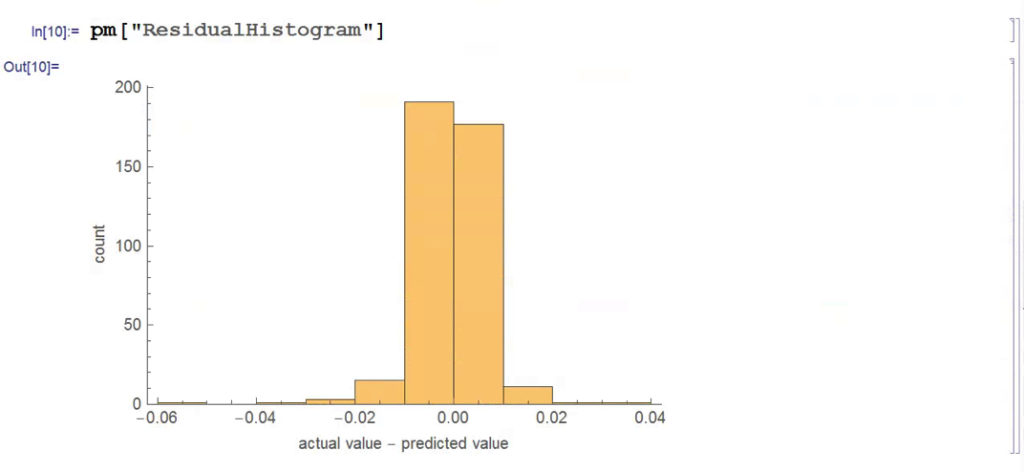

There isn’t much dispersion in the model forecasts, which all have positive value. A common technique in such cases is to subtract the mean from each of the forecasts (and we may also standardize them by dividing by the standard deviation).

The scatterplot of actual vs. forecast overnight returns in SPY now looks like this:

There’s still an obvious lack of dispersion in the forecast values, compared to the actual overnight returns, which we could rectify by standardization. In any event, there appears to be a small, nonlinear relationship between forecast and actual values, which holds out some hope that the model may yet prove useful.

From Forecasting to Trading

There are various methods of deploying a forecasting model in the context of creating a trading system. The simplest route, which we will take here, is to apply a threshold gate and convert the filtered forecasts directly into a trading signal. But other approaches are possible, for example:

- Combining the forecasts from multiple models to create a prediction ensemble

- Using the forecasts as inputs to a genetic programming model

- Feeding the forecasts into the input layer of a neural network model designed specifically to generate trading signals, rather than forecasts

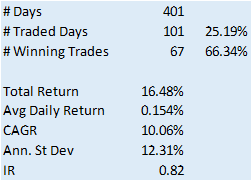

In this example we will create a trading model by applying a simple filter to the forecasts, picking out only those values that exceed a specified threshold. This is a standard trick used to isolate the signal in the model from the background noise. We will accept only the positive signals that exceed the threshold level, creating a long-only trading system. i.e. we ignore forecasts that fall below the threshold level. We buy SPY at the close when the forecast exceeds the threshold and exit any long position at the next day’s open. This strategy produces the following pro-forma results:

Conclusion

The system has some quite attractive features, including a win rate of over 66% and a CAGR of over 10% for the out-of-sample period.

Obviously, this is a very basic illustration: we would want to factor in trading commissions, and the slippage incurred entering and exiting positions in the post- and pre-market periods, which will negatively impact performance, of course. On the other hand, we have barely begun to scratch the surface in terms of the variables that could be considered for inclusion in the feature vector, and which may increase the explanatory power of the model.

In other words, in reality, this is only the beginning of a lengthy and arduous research process. Nonetheless, this simple example should be enough to give the reader a taste of what’s involved in building a predictive trading model using machine learning algorithms.

The Swan of Deadwood

Spending 12-14 hours a day managing investors’ money doesn’t leave me a whole lot of time to sit around watching TV. And since I have probably less than 10% of the ad-tolerance of a typical American audience member, I inevitably turn to TiVo, Netflix, or similar, to watch a commercial-free show. Which means that I am inevitably several years behind the cognoscenti of the au-courant. This has its pluses: I avoid a lot of drivel that way.

So it was that I recently tuned in to watch Deadwood, a masterpiece of modern drama written by the talented David Milch, of NYPD Blue fame. The setting of the show is unpromising: a mud-caked camp in South Dakota around the turn of the 19th century that appears to portend yet another formulaic Western featuring liquor, guns, gals and gold and not much else. The first episode appeared at first to confirm my lowest expectations. I struggled through the second. But by the third I was hooked.

What makes Deadwood such a triumph are its finely crafted plots and intricate sub-plots; the many varied and often complex characters, superbly played by Ian McShane (with outstanding performances by Brad Dourif, Powers Boothe, amongst an abundance of others, no less gifted); and, of course, the dialogue.

Yes, the dialogue: hardly the crowning glory of the typical Hollywood Western. And here, to make matters worse, almost every sentence uttered by many of the characters is replete with such shocking profanity that one is eventually numbed into accepting it as normal. But once you get past that, something strange and rather wonderful overtakes you: a sense of being carried along on a river of creative wordsmith-ing that at times eddies, bubbles, plunges and roars its way through scenes that are as comedic, dramatic and action-packed as any I have seen on film. For those who have yet to enjoy the experience, I offer one small morsel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdJ4TQ3TnNo

Milch as Shakespeare?

Around the start of Series 2 a rather strange idea occurred to me that, try as I might, I was increasingly unable to suppress as the show progressed: that the writing – some of it at least – was almost Shakespearian in its ingenuity and, at times, lyrical complexity.

Convinced that I had taken leave of my senses I turned to Google and discovered, to my surprise, that there is a whole cottage industry of Deadwood fans who had made the same connection. There is even – if you can imagine it – an online quiz that tests if you are able to identify the source of a number of quotes that might come from the show, or one of the Bard’s many plays. I kid you not:

Intrigued, I took the test and scored around 85%. Not too bad for a science graduate, although I expect most English majors would top 90%-95%. That gave me an idea: could one develop a machine learning algorithm to do the job?

Here’s how it went.

Milch or Shakespeare? – A Machine Learning Classification Algorithm

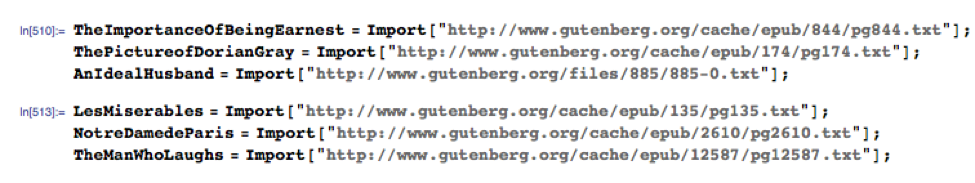

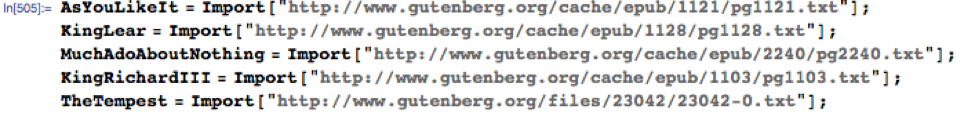

We start by downloading the text of a representative selection of Shakespeare’s plays, avoiding several of the better-known works from which many of the quotations derive:

For testing purposes, let’s download a sample of classic works by other authors:

For testing purposes, let’s download a sample of classic works by other authors:

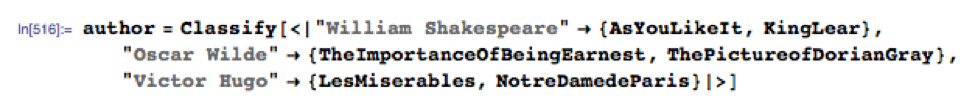

Let’s build an initial test classifier, as follows:

It seems to work ok:

So far so good. Let’s import the script for Deadwood series 1-3:

DeadWood = Import[“……../Dropbox/Documents/Deadwood-Seasons-1-3-script.txt”];

Next, let’s import the quotations used in the online test:

etc

We need to remove the relevant quotes from the Deadwood script file used to train the classifier, of course (otherwise it’s cheating!). We will strip an additional 200 characters before the start of each quotation, and 500 characters after each quotation, just for good measure:

and so on….

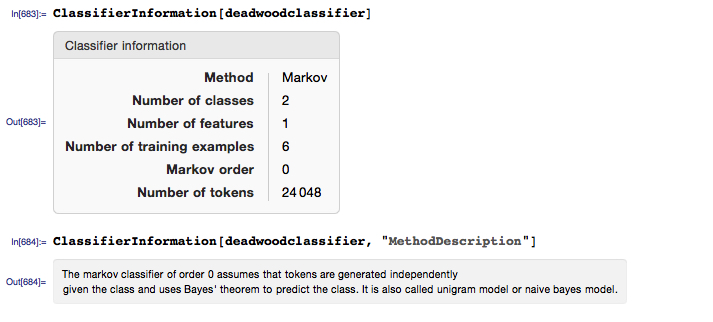

Now we are ready to build our classifier:

And we can obtain some information about the classifier, as follows:

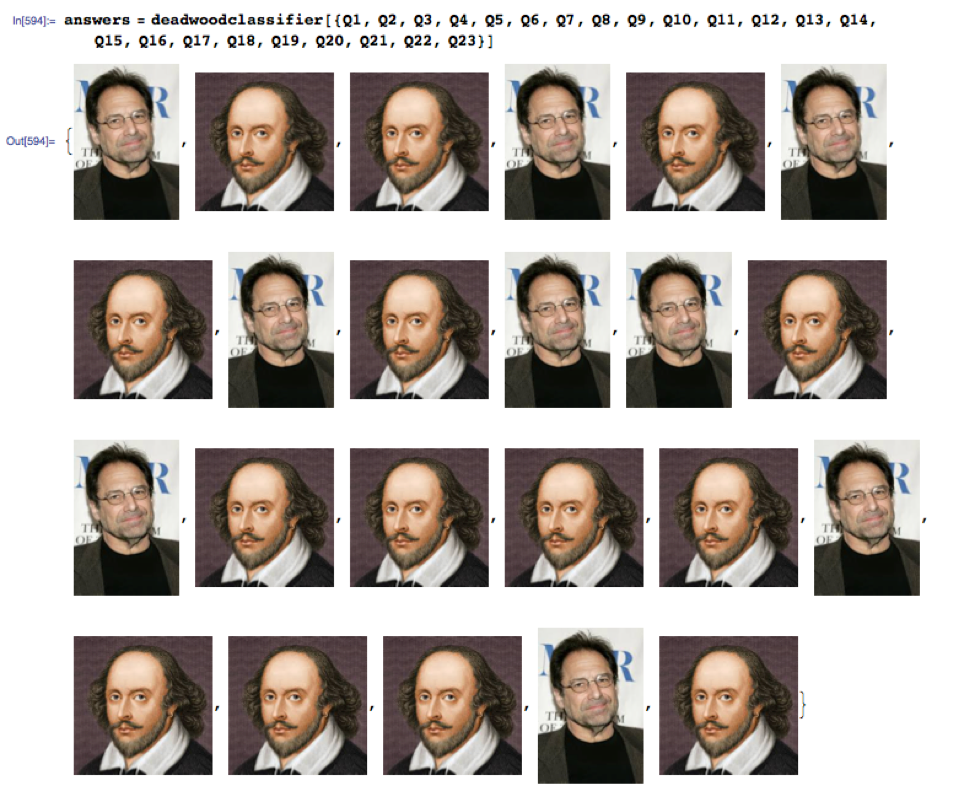

Let’s see how it performs:

Or, if you prefer tabular form:

The machine learning model scored a total of 19 correct answers out of 23, or 82%.

Fooling the Machine

Let’s take a look as some of the questions the algorithm got wrong.

Quotation no. 13 is challenging, as it comes from Pericles, one of Shakespeare’s lesser-know plays and the idiom appears entirely modern. The classifier assigns an 87% probability of Milch being the author (I got it wrong too).

On Quotation no. 15 the algorithm was just as mistaken, but in the other direction (I got this one right, but only because I recalled the monologue from the episode):

Quotation no.16 strikes me as entirely Shakespearian in form and expression and the classifier thought so too, favoring the Bard by 86% to only 14% for Milch:

Quotation no. 19 had the algorithm fooled completely. It’s a perfect illustration of a typical kind of circumlocution favored by Shakespeare that is imitated so well by Milch’s Deadwood characters:

Conclusion

The model clearly picked up distinguishing characteristics of the two authors’ writings that enabled it to correctly classify 82% of the quotations, quite a high percentage and much better than we would expect to do by tossing a coin, for example. It’s a respectable performance, but I might have hoped for greater accuracy from the model, which scored about the same as I did.

I guess those who see parallels in the writing of William Shakespeare and David Milch may be onto something.

Postscript

The Hollywood Reporter recently published a story entitled

“How the $100 Million ‘NYPD Blue’ Creator Gambled Away His Fortune”.

It’s a fascinating account of the trials and tribulations of this great author, one worthy of Deadwood itself.

A silver lining to this tragic tale, perhaps, is that Milch’s difficulties may prompt him into writing the much-desired Series 4.

One can hope.

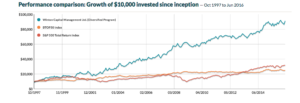

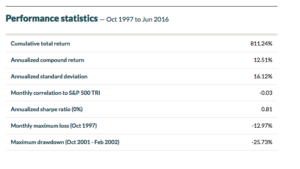

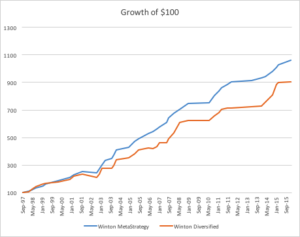

Outperforming Winton Capital

Winton Capital Management is a renowned quant fund and one of the world’s largest, most successful CTAs. The firm’s flagship investment strategy, the Winton Diversified Program, follows a systematic investment process that is based on statistical research to invest globally long and short, using leverage, in a diversified range of liquid instruments, including exchange traded futures, forwards, currency forwards traded over the counter, equity securities and derivatives linked to such securities.

The performance of the program over the last 19 years has been impressive, especially considering its size, which now tops around $13Bn in assets.

Source: CTA Performance

A Meta-Strategy to Beat Winton Capital

With that background, the idea of improving the exceptional results achieved by David Harding and his army of quants seems rather far fetched, but I will take a shot. In what follows, I am assuming that we are permitted to invest and redeem an investment in the program at no additional cost, other than the stipulated fees. This is, of course, something of a stretch, but we will make that assumption based on the further stipulation that we will make no more than two such trades per year.

The procedure we will follow has been described in various earlier posts – in particular see this post, in which I discuss the process of developing a Meta-Strategy: Improving A Hedge Fund Investment – Cantab Capital’s Quantitative Aristarchus Fund

Using the performance data of the WDP from 1997-2012, we develop a meta-strategy that seeks to time an investment in the program, taking profits after reaching a specified profit target, which is based on the TrueRange, or after holding for a maximum of 8 months. The key part of the strategy code is as follows:

If MarketPosition = 1 then begin

TargPrL = EntryPrice + TargFr * TrueRange;

Sell(“ExTarg-L”) next bar at TargPrL limit;

If Time >= TimeEx or BarsSinceEntry >= NBarEx1 or (BarsSinceEntry >= NBarEx3 and C > EntryPrice)

or (BarsSinceEntry >= NBarEx2 and C < EntryPrice) then

Sell(“ExMark-L”) next bar at market;

end;

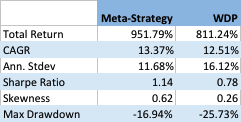

It appears that by timing an investment in the program we can improve the CAGR by around 0.86% per year, and with annual volatility that is lower by around 4.4% annually. As a consequence, the Sharpe ratio of the meta-strategy is considerably higher: 1.14 vs 0.78 for the WDP.

Like most trend-following CTA strategies, Winton’s WDP has positive skewness, an attractive feature that means that the strategy has a preponderance of returns in the positive right tail of the distribution. Also in common with most CTA strategies, on the other hand, the WDP suffers from periodic large drawdowns, in this case amounting to -25.73%.

The meta-strategy improves on the baseline profile of the WDP, increasing the positive skew, while substantially reducing downside risk, leading to a much lower maximum drawdown of -16.94%.

Conclusion

Despite its stellar reputation in the CTA world, investors could theoretically improve on the performance of Winton Capital’s flagship program by using a simple meta-strategy that times entry to and exit from the program using simple technical indicators. The meta-strategy produces higher returns, lower volatility and with higher positive skewness and lower downside risk.