Decay in Leveraged ETFs

Leveraged ETFs continue to be much discussed on Seeking Alpha.

One aspect in particular that has caught analysts’ attention is the decay, or “beta slippage” that leveraged ETFs tend to suffer from.

Seeking Alpha contributor Fred Picard in a 2013 article (“What You Need To Know About The Decay Of Leveraged ETFs“) described the effect using the following hypothetical example:

To understand what is beta-slippage, imagine a very volatile asset that goes up 25% one day and down 20% the day after. A perfect double leveraged ETF goes up 50% the first day and down 40% the second day. On the close of the second day, the underlying asset is back to its initial price:

(1 + 0.25) x (1 – 0.2) = 1

And the perfect leveraged ETF?

(1 + 0.5) x (1 – 0.4) = 0.9

Nothing has changed for the underlying asset, and 10% of your money has disappeared. Beta-slippage is not a scam. It is the normal mathematical behavior of a leveraged and rebalanced portfolio. In case you manage a leveraged portfolio and rebalance it on a regular basis, you create your own beta-slippage. The previous example is simple, but beta-slippage is not simple. It cannot be calculated from statistical parameters. It depends on a specific sequence of gains and losses.

Fred goes on to make the point that is the crux of this article, as follows:

At this point, I’m sure that some smart readers have seen an opportunity: if we lose money on the long side, we make a profit on the short side, right?

Shorting Leveraged ETFs

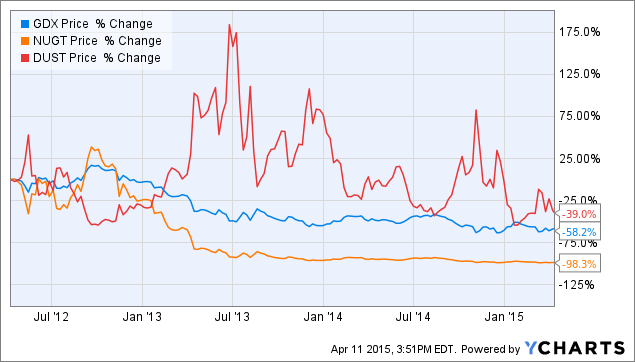

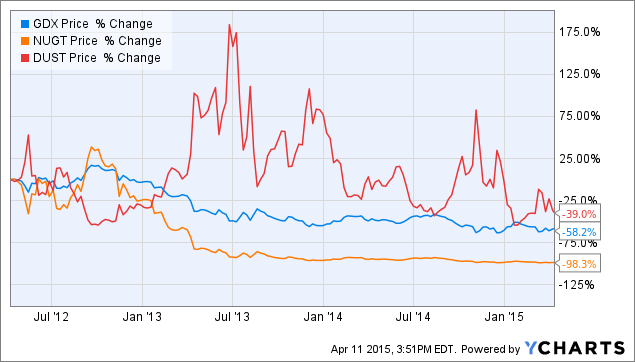

Taking his cue from Fred’s article, Seeking Alpha contributor Stanford Chemist (“Shorting Leveraged ETF Pairs: Easier Said Than Done“) considers the outcome of shorting pairs of leveraged ETFs, including the Market Vectors Gold Miners ETF (NYSEARCA:GDX), the Direxion Daily Gold Miners Bull 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:NUGT) and the Direxion Daily Gold Miners Bear 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:DUST).

His initial finding appears promising:

Therefore, investing $10,000 each into short positions of NUGT and DUST would have generated a profit of $9,830 for NUGT, and $3,900 for DUST, good for an average profit of 68.7% over 3 years, or 22.9% annualized.

At first sight, this appears to a nearly risk-free strategy; after all, you are shorting both the 3X leveraged bull and 3X leveraged bear funds, which should result in a market neutral position. Is there easy money to be made?

Source: Standford Chemist

Not so fast! Stanford Chemist applies the same strategy to another ETF pair, with a very different outcome:

“What if you had instead invested $10,000 each into short positions of the Direxion Russell 1000 Financials Bullish 3X ETF (NYSEARCA:FAS) and the Direxion Russell 1000 Financials Bearish 3X ETF (NYSEARCA:FAZ)?

The $10,000 short position in FAZ would have gained you $8,680. However, this would have been dwarfed by the $28,350 loss that you would have sustained in shorting FAS. In total, you would be down $19,670, which translates into a loss of 196.7% over three years, or 65.6% annualized.

No free lunch there.

The Rebalancing Issue

Stanford Chemist puts his finger on one of the key issues: rebalancing. He explains as follows:

So what happened to the FAS-FAZ pair? Essentially, what transpired was that as the underlying asset XLF increased in value, the two short positions became unbalanced. The losing side (short FAS) ballooned in size, making further losses more severe. On the other hand, the winning side (short FAZ) shrunk, muting the effect of further gains.

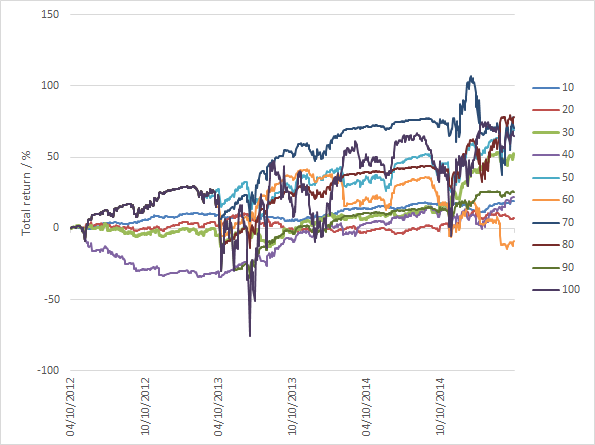

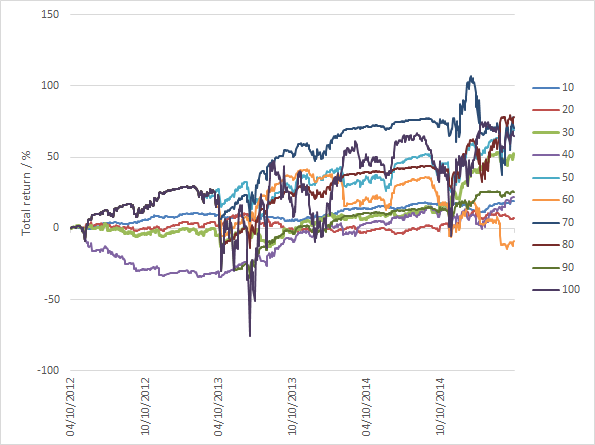

To counteract this effect, the portfolio needs to be rebalanced. Stanford Chemist looks at the implications of rebalancing a short NUGT-DUST portfolio whenever the market value of either ETF deviates by more than N% from its average value, where he considers N% in the range from 10% to 100%, in increments of 10%.

While the annual portfolio return was positive in all but one of these scenarios, there was very considerable variation in the outcomes, with several of the rebalanced portfolios suffering very large drawdowns of as much as 75%:

Source: Stanford Chemist

The author concludes:

The results of the backtest showed that profiting from this strategy is easier said than done. The total return performances of the strategy over the past three years was highly dependent on the rebalancing thresholds chosen. Unfortunately, there was also no clear correlation between the rebalancing period used and the total return performance. Moreover, the total return profiles showed that large drawdowns do occur, meaning that despite being ostensibly “market neutral”, this strategy still bears a significant amount of risk.

Leveraged ETF Pairs – Four Case Studies

Let’s press pause here and review a little financial theory. As you recall, it is possible to express a rate of return in many different ways, depending on how interest is compounded. The most typical case is daily compounding:

R = (Pt – Pt-1) / Pt

Where Pt is the price on day t, and Pt-1 is the price on day t-1, one day prior.

Another commonly used alternative is continuous compounding, also sometimes called log-returns:

R = Ln(Pt) – Ln(Pt-1)

Where Ln(Pt) is the natural log of the price on day t, Pt

When a writer refers to a rate of return, he should make clear what compounding basis the return rate is quoted on, whether continuous, daily, monthly or some other frequency. Usually, however, the compounding basis is clear from the context. Besides, it often doesn’t make a large difference anyway. But with leveraged ETFs, even microscopic differences can produce substantially different outcomes.

I will illustrate the effect of compounding by reference to examples of portfolios comprising short positions in the following representative pairs of leveraged ETFs:

- Direxion Daily Energy Bull 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:ERX)

- Direxion Daily Energy Bear 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:ERY)

- Direxion Daily Gold Miners Bull 3X ETF

- Direxion Daily Gold Miners Bear 3X ETF

- Direxion Daily S&P 500 Bull 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:SPXL)

- Direxion Daily S&P 500 Bear 3X Shares ETF (NYSEARCA:SPXS)

- Direxion Daily Small Cap Bull 3X ETF (NYSEARCA:TNA)

- Direxion Daily Small Cap Bear 3X ETF (NYSEARCA:TZA)

The findings in relation to these pairs are mirrored by results for other leveraged ETF pairs.

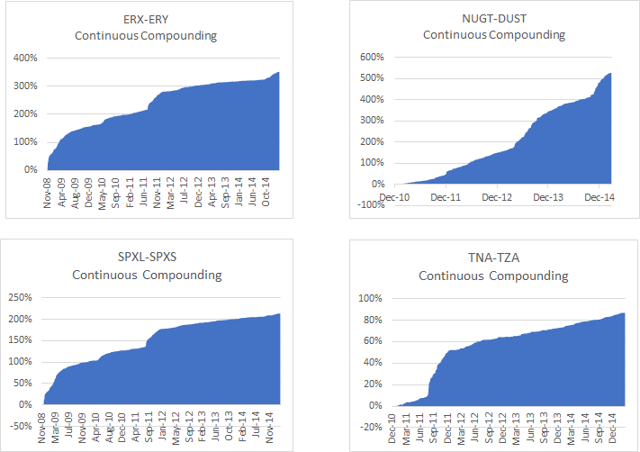

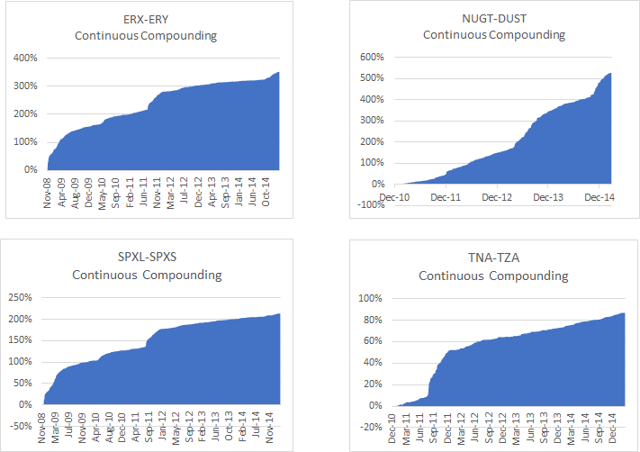

First, let’s look the returns in the ETF portfolios measured using continuous compounding.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

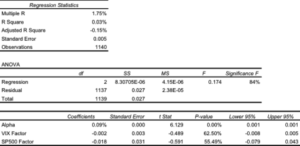

The portfolio returns look very impressive, with CAGRs ranging from around 20% for the short TNA-TZA pair, to over 124% for the short NUGT-DUST pair. Sharpe ratios, too, appear abnormally large, ranging from 4.5 for the ERX-ERY short pair to 8.4 for NUGT-DUST.

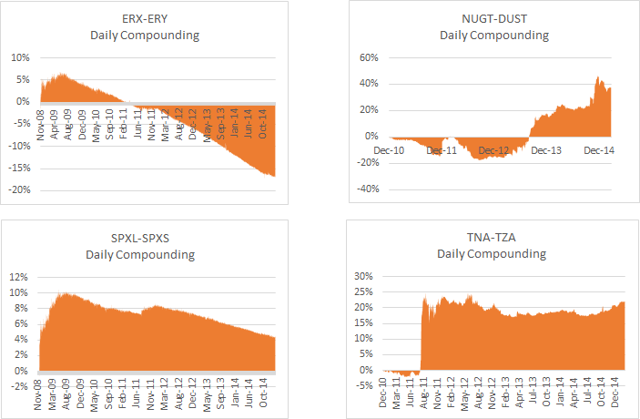

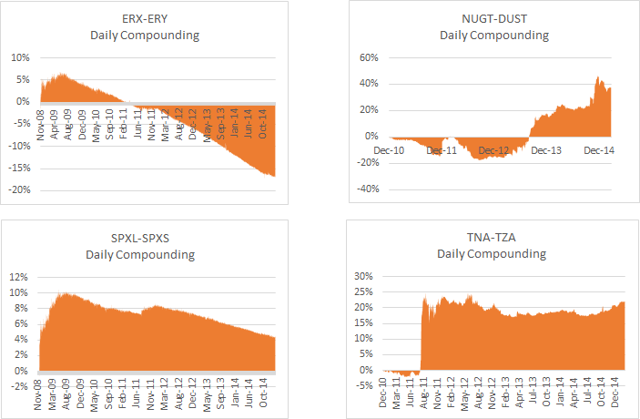

Now let’s look at the performance of the same portfolios measured using daily compounding.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

It’s an altogether different picture. None of the portfolios demonstrate an attract performance record and indeed in two cases the CAGR is negative.

What’s going on?

Stock Loan Costs

Before providing the explanation, let’s just get one important detail out of the way. Since you are shorting both legs of the ETF pairs, you will be faced with paying stock borrow costs. Borrow costs for leveraged ETFs can be substantial and depending on market conditions amount to as much as 10% per annum, or more.

In computing the portfolio returns in both the continuous and daily compounding scenarios I have deducted annual stock borrow costs based on recent average quotes from Interactive Brokers, as follows:

- ERX-ERY: 14%

- NUGT-DUST: 16%

- SXPL-SPXS: 8%

- TNA-TZA: 8%

It’s All About Compounding and Rebalancing

The implicit assumption in the computation of the daily compounded returns shown above is that you are rebalancing the portfolios each day. That is to say, it is assumed that at the end of each day you buy or sell sufficient quantities of shares of each ETF to maintain an equal $ value in both legs.

In the case of continuously compounded returns the assumption you are making is that you maintain an equal $ value in both legs of the portfolio at every instant. Clearly that is impossible.

Ok, so if the results from low frequency rebalancing are poor, while the results for instantaneous rebalancing are excellent, it is surely just a question of rebalancing the portfolio as frequently as is practically possible. While we may not be able to achieve the ideal result from continuous rebalancing, the results we can achieve in practice will reflect how close we can come to that ideal, right?

Unfortunately, not.

Because, while we have accounted for stock borrow costs, what we have ignored in the analysis so far are transaction costs.

Transaction Costs

With daily rebalancing transaction costs are unlikely to be a critical factor – one might execute a single trade towards the end of the trading session. But in the continuous case, it’s a different matter altogether.

Let’s use the SPXL-SPXS pair as an illustration. When the S&P 500 index declines, the value of the SPXL ETF will fall, while the value of the SPXS ETF will rise. In order to maintain the same $ value in both legs you will need to sell more shares in SPXL and buy back some shares in SPXS. If the market trades up, SPXL will increase in value, while the price of SPXS will fall, requiring you to buy back some SPXL shares and sell more SPXS.

In other words, to rebalance the portfolio you will always be trying to sell the ETF that has declined in price, while attempting to buy the inverse ETF that has appreciated. It is often very difficult to execute a sale in a declining stock at the offer price, or buy an advancing stock at the inside bid. To be sure of completing the required rebalancing of the portfolio, you are going to have to buy at the ask price and sell at the bid price, paying the bid-offer spread each time.

Spreads in leveraged ETF products tend to be large, often several pennies. The cumulative effect of repeatedly paying the bid-ask spread, while taking trading losses on shares sold at the low or bought at the high, will be sufficient to overwhelm the return you might otherwise hope to make from the ETF decay.

And that’s assuming the best case scenario that shares are always available to short. Often they may not be: so that, if the market trades down and you need to sell more SPXL, there may be none available and you will be unable to rebalance your portfolio, even if you were willing to pay the additional stock loan costs and bid-ask spread.

A Lose-Lose Proposition

So, in summary: if you rebalance infrequently you will avoid excessive transaction costs; but the $ imbalance that accrues over the course of a trading day will introduce a market bias in the portfolio. That can hurt portfolio returns very badly if you get caught on the wrong side of a major market move. The results from daily rebalancing for the illustrative pairs shown above indicate that this is likely to happen all too often.

On the other hand, if you try to maintain market neutrality in the portfolio by rebalancing at high frequency, the returns you earn from decay will be eaten up by transaction costs and trading losses, as you continuously sell low and buy high, paying the bid-ask spread each time.

Either way, you lose.

Ok, what about if you reverse the polarity of the portfolio, going long both legs? Won’t that avoid the very high stock borrow costs and put you in a better position as regards the transaction costs involved in rebalancing?

Yes, it will. Because, you will be selling when the market trades up and buying when it falls, making it much easier to avoid paying the bid-ask spread. You will also tend to make short term trading profits by selling high and buying low. Unfortunately, you may not be surprised to learn, these advantages are outweighed by the cost of the decay incurred in both legs of the long ETF portfolio.

In other words: you can expect to lose if you are short; and lose if you are long!

An Analogy from Option Theory

To anyone with a little knowledge of basic option theory, what I have been describing should sound like familiar territory.

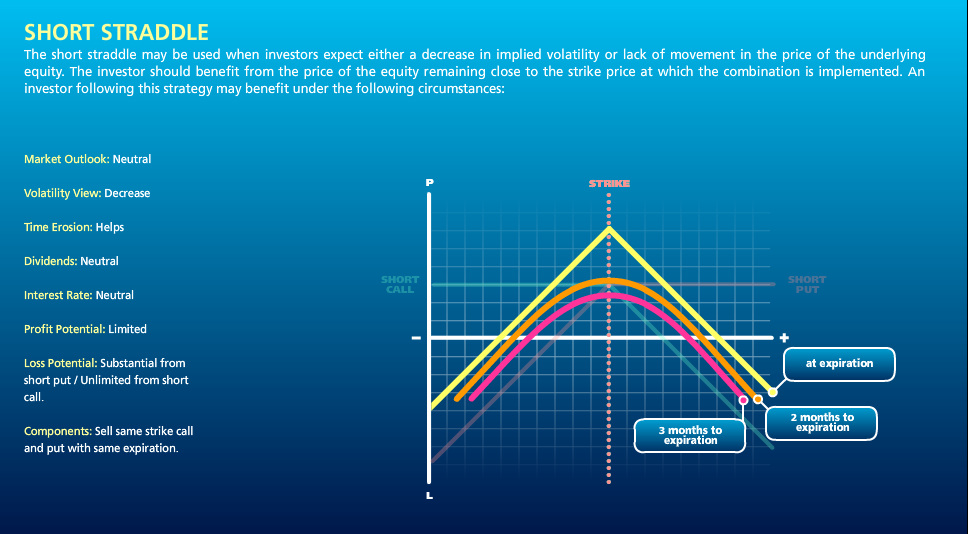

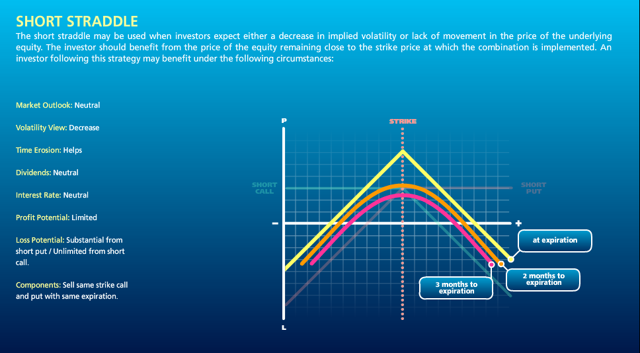

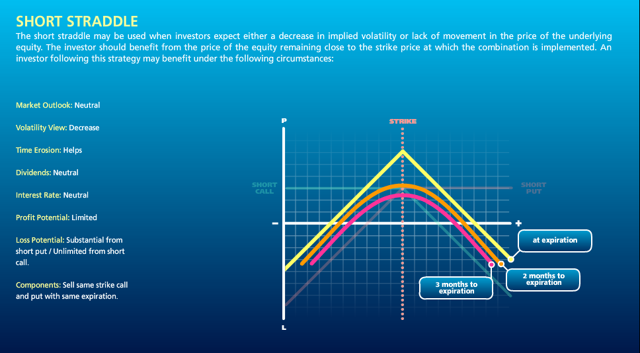

Being short the ETF pair is like being short an option (actually a pair of call and put options, called a straddle). You earn decay, or Theta, for those familiar with the jargon, by earning the premium on the options you have sold; but at the risk of being short Gamma – which measures your exposure to a major market move.

Source: Interactive Brokers

You can hedge out the portfolio’s Gamma exposure by trading the underlying securities – the ETF pair in this case – and when you do that you find yourself always having to sell at the low and buy at the high. If the options are fairly priced, the option decay is enough, but not more, to compensate for the hedging cost involved in continuously trading the underlying.

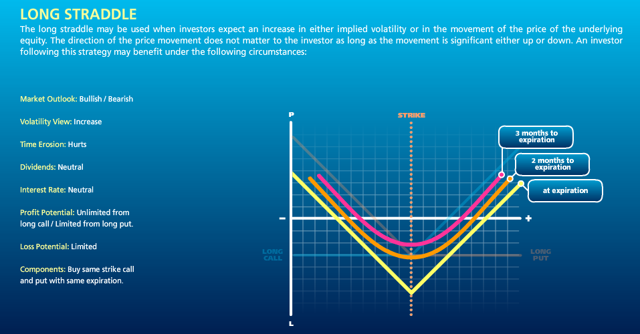

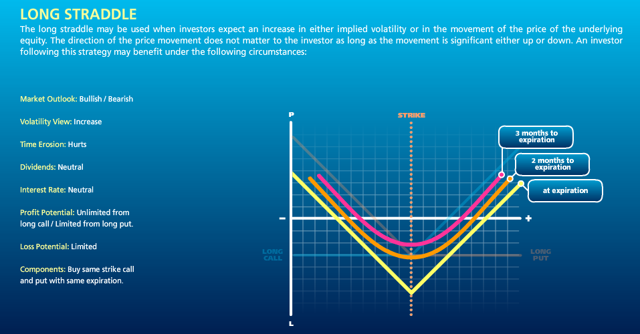

Conversely, being long the ETF pair is like being long a straddle on the underling pair. You now have positive Gamma exposure, so your portfolio will make money from a major market move in either direction. However, the value of the straddle, initially the premium you paid, decays over time at a rate Theta (also known as the “bleed”).

Source: Interactive Brokers

You can offset the bleed by performing what is known as Gamma trading. When the market trades up your portfolio delta becomes positive, i.e. an excess $ value in the long ETF leg, enabling you to rebalance your position by selling excess deltas at the high. Conversely, when the market trades down, your portfolio delta becomes negative and you rebalance by buying the underlying at the current, reduced price. In other words, you sell at the high and buy at the low, typically making money each time. If the straddle is fairly priced, the profits you make from Gamma trading will be sufficient to offset the bleed, but not more.

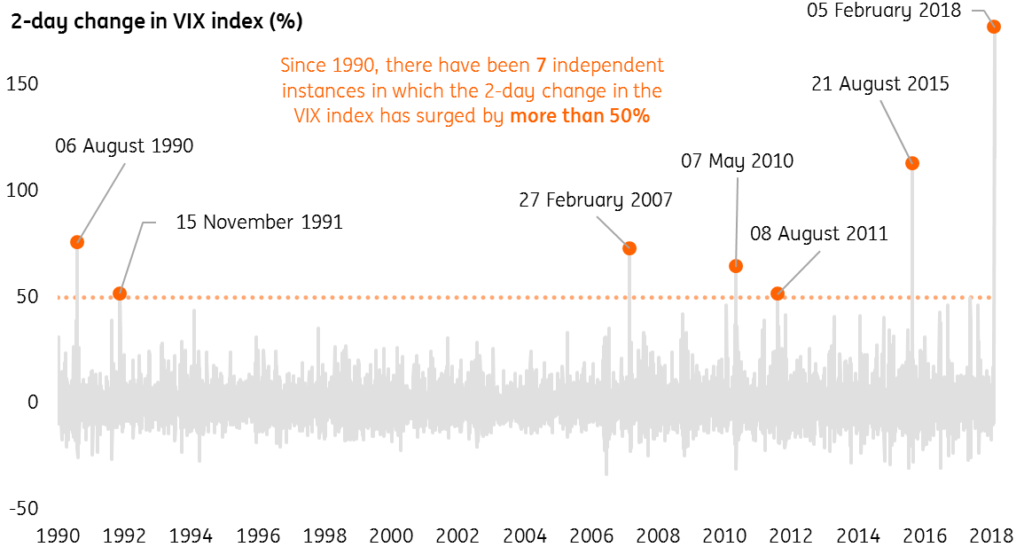

Typically, the payoff from being short options – being short the ETF pair – will show consistent returns for sustained periods, punctuated by very large losses when the market makes a significant move in either direction.

Conversely, if you are long options – long the ETF pair – you will lose money most of the time due to decay and occasionally make a very large profit.

In an efficient market in which securities are fairly priced, neither long nor short option strategy can be expected to dominate the other in the long run. In fact, transaction costs will tend to produce an adverse outcome in either case! As with most things in life, the house is the player most likely to win.

Developing a Leveraged ETF Strategy that Works

Investors shouldn’t be surprised that it is hard to make money simply by shorting leveraged ETF pairs, just as it is hard to make money by selling options, without risking blowing up your account.

And yet, many traders do trade options and often manage to make substantial profits. In some cases traders are simply selling options, hoping to earn substantial option premiums without taking too great a hit when the market explodes. They may get away with it for many years, before blowing up. Indeed, that has been the case since 2009. But who would want to be an option seller here, with the market at an all-time high? It’s simply far too risky.

The best option traders make money by trading both the long and the short side. Sure, they might lean in one direction or the other, depending on their overall market view and the opportunities they find. But they are always hedged, to some degree. In essence what many option traders seek to do is what is known as relative value trading – selling options they regard as expensive, while hedging with options they see as being underpriced. Put another way, relative value traders try to buy cheap Gamma and sell expensive Theta.

This is how one can thread the needle in leveraged ETF strategies. You can’t hope to make money simply by being long or short all the time – you need to create a long/short ETF portfolio in which the decay in the ETFs you are short is greater than in the ETFs you are long. Such a strategy is, necessarily, tactical: your portfolio holdings and net exposure will likely change from long to short, or vice versa, as market conditions shift. There will be times when you will use leverage to increase your market exposure and occasions when you want to reduce it, even to the point of exiting the market altogether.

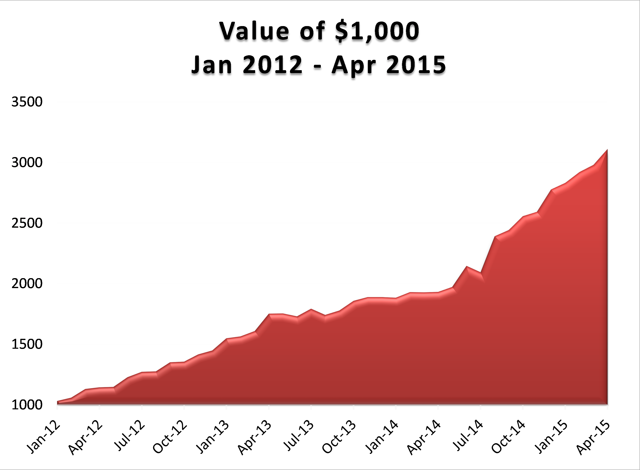

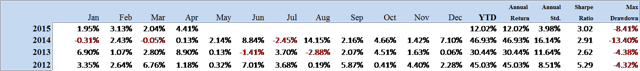

If that sounds rather complicated, I’m afraid it is. I have been developing and trading arbitrage strategies of this kind since the early 2000s, often using sophisticated option pricing models. In 2012 I began trading a volatility strategy in ETFs, using a variety of volatility ETF products, in combination with equity and volatility index futures.

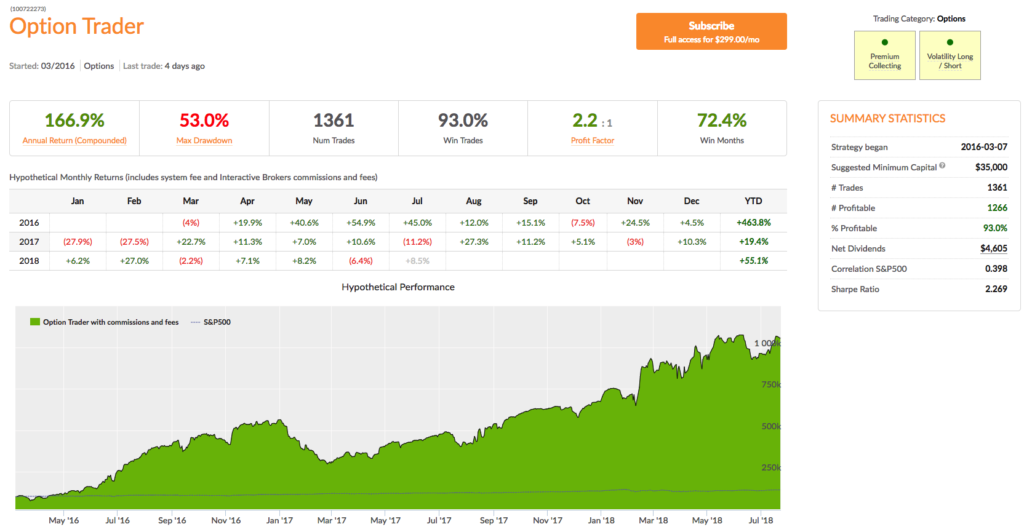

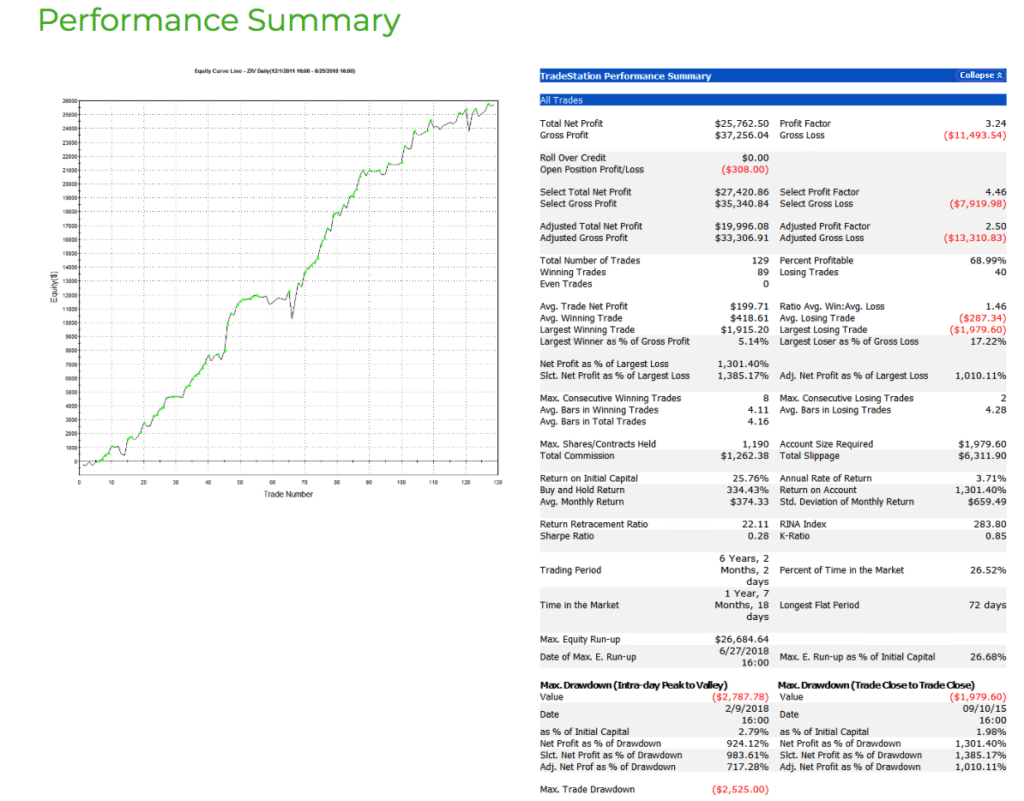

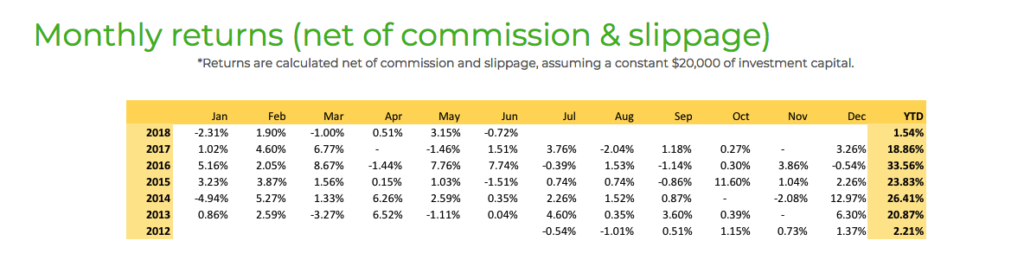

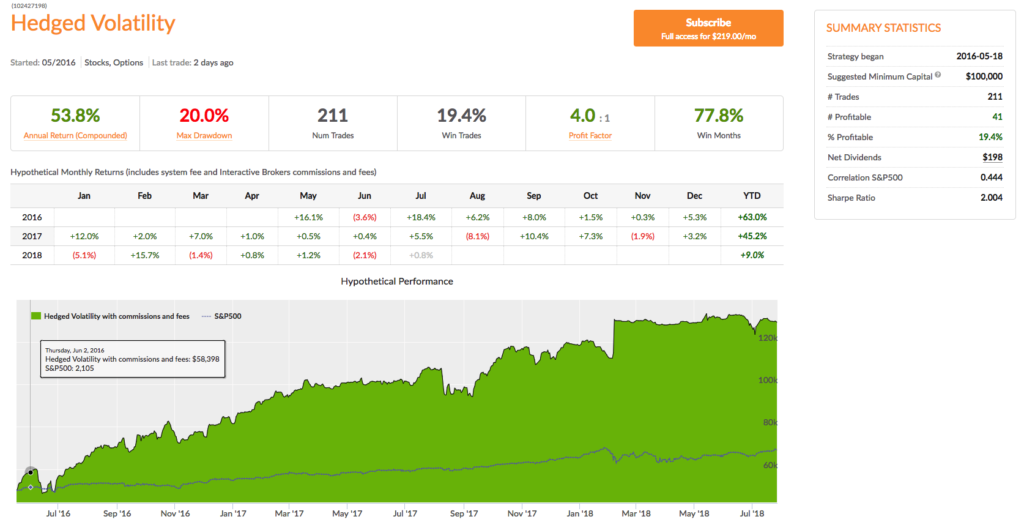

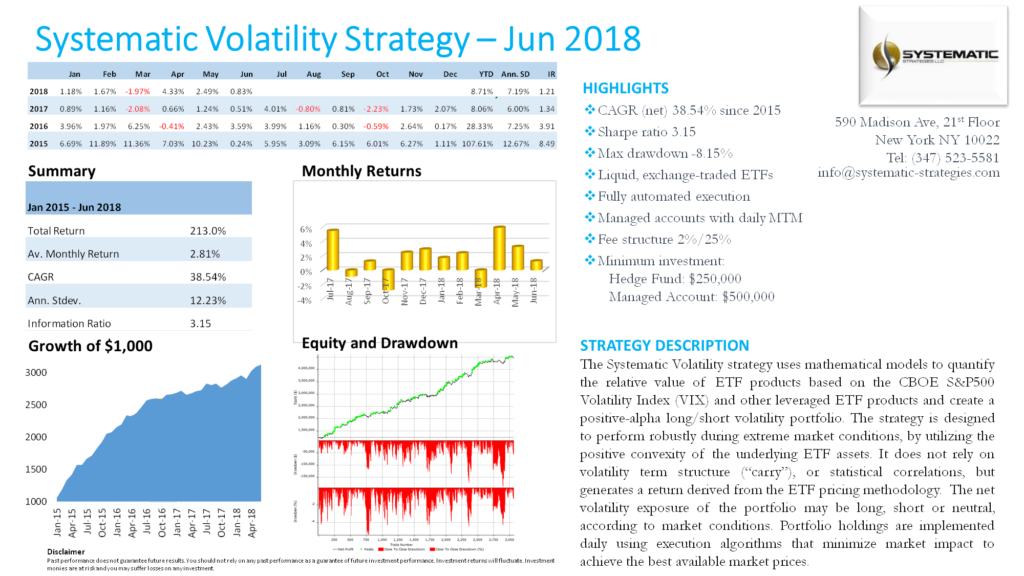

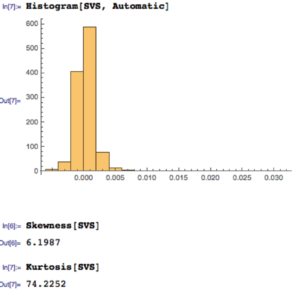

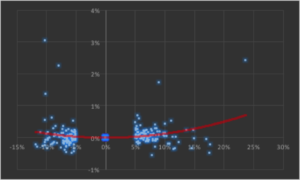

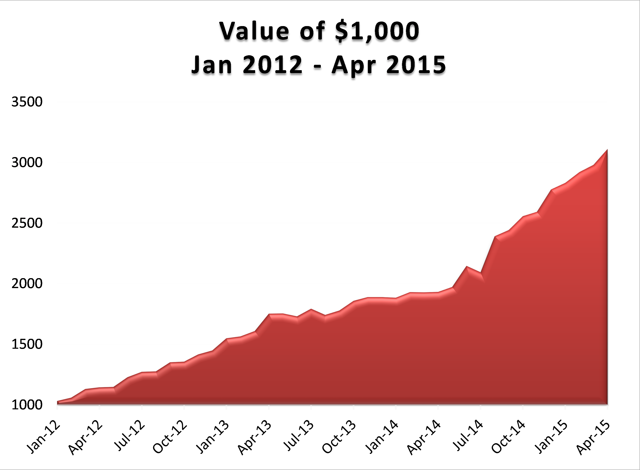

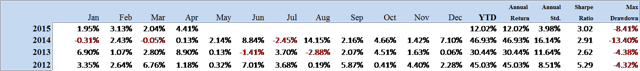

I have reproduced the results from that strategy below, to give some indication of what is achievable in the ETF space using relative value arbitrage techniques.

Source: Systematic Strategies, LLC

Source: Systematic Strategies, LLC

Source: Systematic Strategies LLC

Conclusion

There are no free lunches in the market. The apparent high performance of strategies that engage systematically in shorting leveraged ETFs is an illusion, based on a failure to quantify the full costs of portfolio rebalancing.

The payoff from a short leveraged ETF pair strategy will be comparable to that of a short straddle position, with positive decay (Theta) and negative Gamma (exposure to market moves). Such a strategy will produce positive returns most of the time, punctuated by very large drawdowns.

The short Gamma exposure can be mitigated by continuously rebalancing the portfolio to maintain dollar neutrality. However, this will entail repeatedly buying ETFs as they trade up and selling them as they decline in value. The transaction costs and trading losses involved in continually buying high and selling low will eat up most, if not all, of the value of the decay in the ETF legs.

A better approach to trading ETFs is relative value arbitrage, in which ETFs with high decay rates are sold and hedged by purchases of ETFs with relatively low rates of decay.

An example given of how this approach has been applied successfully in volatility ETFs since 2012.