The infatuation of futures traders with the subject of money management, (more aptly described as position sizing), is something of a puzzle for someone coming from a background in equities or forex. The idea is, simply, that one can improve one’s trading performance through the judicious use of leverage, increasing the size of a position at times and reducing it at others.

Perhaps the most widely known money management technique is the Martingale, where the size of the trade is doubled after every loss. It is easy to show mathematically that such a system must win eventually, provided that the bet size is unlimited. It is also easy to show that, small as it may be, there is a non-zero probability of a long string of losing trades that would bankrupt the trader before he was able to recoup all his losses. Still, the prospect offered by the Martingale strategy is an alluring one: the idea that, no matter what the underlying trading strategy, one can eventually be certain of winning. And so a virtual cottage industry of money management techniques has evolved.

One of the reasons why the money management concept is prevalent in the futures industry compared to, say, equities or f/x, is simply the trading mechanics. Doubling the size of a position in futures might mean trading an extra contract, or perhaps a ten-lot; doing the same in equities might mean scaling into and out of multiple positions comprising many thousands of shares. The execution risk and cost of trying to implement a money management program in equities has historically made the idea infeasible, although that is less true today, given the decline in commission rates and the arrival of smart execution algorithms. Still, money management is a concept that originated in the futures industry and will forever be associated with it.

Van Tharp on Position Sizing

I was recently recommended to read Van Tharp’s Definitive Guide to Position Sizing, which devotes several hundred pages to the subject. Leaving aside the great number of pages of simulation results, there is much to commend it. Van Tharp does a pretty good job of demolishing highly speculative and very dangerous “money management” techniques such as the Kelly Criterion and Ralph Vince’s Optimal f, which make unrealistic assumptions of one kind or another, such as, for example, that there are only two outcomes, rather than the multiple possibilities from a trading strategy, or considering only the outcome of a single trade, rather than a succession of trades (whose outcome may not be independent). Just as with the Martingale, these techniques will often produce unacceptably large drawdowns. In fact, as I have pointed out elsewhere, the use of leverage which many so-called money management techniques actually calls for increases in the risk in the original strategy, often reducing its risk-adjusted return.

As Van Tharp points out, mathematical literacy is not one of the strongest suits of futures traders in general and the money management strategy industry reflects that.

But Van Tharp himself is not immune to misunderstanding mathematical concepts. His central idea is that trading systems should be rated according to its System Quality Number, which he defines as:

SQN = (Expectancy / standard deviation of R) * square root of Number of Trades

R is a central concept of Van Tharp’s methodology, which he defines as how much you will lose per unit of your investment. So, for example, if you buy a stock today for $50 and plan to sell it if it reaches $40, your R is $10. In cases like this you have a clear definition of your R. But what if you don’t? Van Tharp sensibly recommends you use your average loss as an estimate of R.

Expectancy, as Van Tharp defines it, is just the expected profit per trade of the system expressed as a multiple of R. So

SQN = ( (Average Profit per Trade / R) / standard deviation (Average Profit per Trade / R) * square root of Number of Trades

Squaring both sides of the equation, we get:

SQN^2 = ( (Average Profit per Trade )^2 / R^2) / Variance (Average Profit per Trade / R) ) * Number of Trades

The R-squared terms cancel out, leaving the following:

SQN^2 = ((Average Profit per Trade ) ^ 2 / Variance (Average Profit per Trade)) * Number of Trades

Hence,

SQN = (Average Profit per Trade / Standard Deviation (Average Profit per Trade)) * square root of Number of Trades

There is another name by which this measure is more widely known in the investment community: the Sharpe Ratio.

On the “Optimal” Position Sizing Strategy

In my view, Van Tharp’s singular achievement has been to spawn a cottage industry out of restating a fact already widely known amongst investment professionals, i.e. that one should seek out strategies that maximize the Sharpe Ratio.

Not that seeking to maximize the Sharpe Ratio is a bad idea – far from it. But then Van Tharp goes on to suggest that one should consider only strategies with a SQN of greater than 2, ideally much higher (he mentions SQNs of the order of 3-6).

But 95% or more of investable strategies have a Sharpe Ratio less than 2. In fact, in the world of investment management a Sharpe Ratio of 1.5 is considered very good. Barely a handful of funds have demonstrated an ability to maintain a Sharpe Ratio of greater than 2 over a sustained period (Jim Simon’s Renaissance Technologies being one of them). Only in the world of high frequency trading do strategies typically attain the kind of Sharpe Ratio (or SQN) that Van Tharp advocates. So while Van Tharp’s intentions are well meaning, his prescription is unrealistic, for the majority of investors.

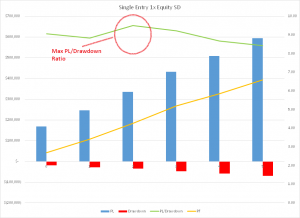

One recommendation of Van Tharp’s that should be taken seriously is that there is no single “best” money management strategy that suits every investor. Instead, position sizing should be evolved through simulation, taking into account each trader or investor’s preferences in terms of risk and return. This makes complete sense: a trader looking to make 100% a year and willing to risk 50% of his capital is going to adopt a very different approach to money management, compared to an investor who will be satisfied with a 10% return, provided his risk of losing money is very low. Again, however, there is nothing new here: the problem of optimal allocation based on an investor’s aversion to risk has been thoroughly addressed in the literature for at least the last 50 years.

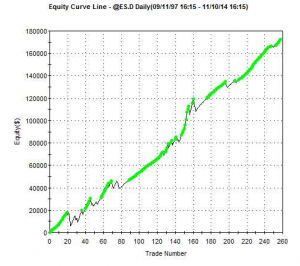

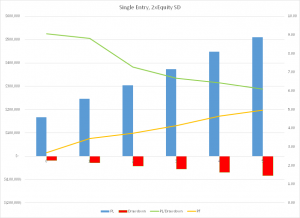

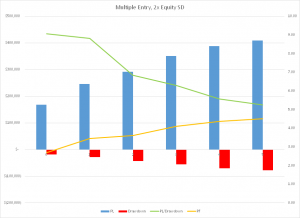

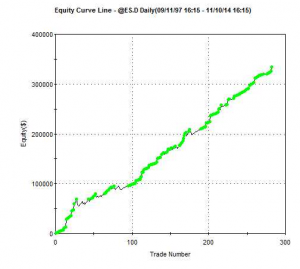

What about the Equity Curve Money Management strategy I discussed in a previous post? Isn’t that a kind of Martingale? Yes and no. Indeed, the strategy does require us to increase the original investment after a period of loss. But it does so, not after a single losing trade, but after a series of losses from which the strategy is showing evidence of recovering. Furthermore, the ECMM system caps the add-on investment at some specified level, rather than continuing to double the trade size after every loss, as in a Martingale.

But the critical difference between the ECMM and the standard Martingale lies in the assumptions about dependency in the returns of the underlying strategy. In the traditional Martingale, profits and losses are independent from one trade to the next. By contrast, scenarios where ECMM is likely to prove effective are ones where there is dependency in the underlying strategy, more specifically, negative autocorrelation in returns over some horizon. What that means is that periods of losses or lower returns tend to be followed by periods of gains, or higher returns. In other words, ECMM works when the underlying strategy has a tendency towards mean reversion.

CONCLUSION

The futures industry has spawned a myriad of position sizing strategies. Many are impractical, or positively dangerous, leading as they do to significant risk of catastrophic loss. Generally, investors should seek out strategies with higher Sharpe Ratios, and use money management techniques only to improve the risk-adjusted return. But there is no universal money management methodology that will suit every investor. Instead, money management should be conditioned on each individual investors risk preferences.