One of the challenges with the cointegration approach to statistical arbitrage which I discussed in my previous post, is that cointegration relationships are seldom static: they change quite frequently and often break down completely. Back in 2009 I began experimenting with a more dynamic approach to pairs trading, based on the Kalman Filter.

In its simplest form, we model the relationship between a pair of securities in the following way:

beta(t) = beta(t-1) + w beta(t), the unobserved state variable, that follows a random walk

Y(t) = beta(t)X(t) + v The observed processes of stock prices Y(t) and X(t)

where:

w ~ N(0,Q) meaning w is gaussian noise with zero mean and variance Q

v ~ N(0,R) meaning v is gaussian noise with variance R

So this is just like the usual pairs relationship Y = beta * X + v, where the typical approach is to estimate beta using least squares regression, or some kind of rolling regression (to try to take account of the fact that beta may change over time). In this traditional framework, beta is static, or slowly changing.

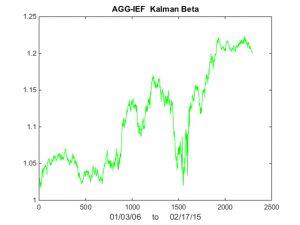

In the Kalman framework, beta is itself a random process that evolves continuously over time, as a random walk. Because it is random and contaminated by noise we cannot observe beta directly, but must infer its (changing) value from the observable stock prices X and Y. (Note: in what follows I shall use X and Y to refer to stock prices. But you could also use log prices, or returns).

Unknown to me at that time, several other researchers were thinking along the same lines and later published their research. One such example is Statistical Arbitrage and High-Frequency Data with an Application to Eurostoxx 50 Equities, Rudy, Dunis, Giorgioni and Laws, 2010. Another closely related study is Performance Analysis of Pairs Trading Strategy Utilizing High Frequency Data with an Application to KOSPI 100 Equities, Kim, 2011. Both research studies follow a very similar path, rejecting beta estimation using rolling regression or exponential smoothing in favor of the Kalman approach and applying a Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model to estimate the half-life of mean reversion of the pairs portfolios. The studies report very high out-of-sample information ratios that in some cases exceed 3.

I have already made the point that such unusually high performance is typically the result of ignoring the fact that the net PnL per share may lie within the region of the average bid-offer spread, making implementation highly problematic. In this post I want to dwell on another critical issue that is particular to the Kalman approach: the signal:noise ratio, Q/R, which expresses the ratio of the variance of the beta process to that of the price process. (Curiously, both papers make the same mistake of labelling Q and R as standard deviations. In fact, they are variances).

Beta, being a random process, obviously contains some noise: but the hope is that it is less noisy than the price process. The idea is that the relationship between two stocks is more stable – less volatile – than the stock processes themselves. On its face, that assumption appears reasonable, from an empirical standpoint. The question is: how stable is the beta process, relative to the price process? If the variance in the beta process is low relative to the price process, we can determine beta quite accurately over time and so obtain accurate estimates of the true price Y(t), based on X(t). Then, if we observe a big enough departure in the quoted price Y(t) from the true price at time t, we have a potential trade.

In other words, we are interested in:

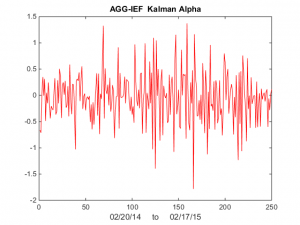

alpha(t) = Y(t) – Y*(t) = Y(t) – beta(t) X(t)

where Y(t) and X(t) are the observed stock prices and beta(t) is the estimated value of beta at time t.

As usual, we would standardize the alpha using an estimate of the alpha standard deviation, which is sqrt(R). (Alternatively, you can estimate the standard deviation of the alpha directly, using a lookback period based on the alpha half-life).

If the standardized alpha is large enough, the model suggests that the price Y(t) is quoted significantly in excess of the true value. Hence we would short stock Y and buy stock X. (In this context, where X and Y represent raw prices, you would hold an equal and opposite number of shares in Y and X. If X and Y represented returns, you would hold equal and opposite market value in each stock).

The success of such a strategy depends critically on the quality of our estimates of alpha, which in turn rest on the accuracy of our estimates of beta. This depends on the noisiness of the beta process, i.e. its variance, Q. If the beta process is very noisy, i.e. if Q is large, our estimates of alpha are going to be too noisy to be useful as the basis for a reversion strategy.

So, the key question I want to address in this post is: in order for the Kalman approach to be effective in modeling a pairs relationship, what would be an acceptable range for the beta process variance Q ? (It is often said that what matters in the Kalman framework is not the variance Q, per se, but rather the signal:noise ratio Q/R. It turns out that this is not strictly true, as we shall see).

To get a handle on the problem, I have taken the following approach:

(i) Simulate a stock process X(t) as a geometric brownian motion process with specified drift and volatility (I used 0%, 5% and 10% for the annual drift, and 10%, 30% and 60% for the corresponding annual volatility).

(ii) simulate a beta(t) process as a random walk with variance Q in the range from 1E-10 to 1E-1.

(iii) Generate the true price process Y(t) = beta(t)* X(t)

(iv) Simulate an observed price process Yobs(t), by adding random noise with variance R to Y(t), with R in the range 1E-6 to 1.0

(v) Calculate the true, known alpha(t) = Y(t) – Yobs(t)

(vi) Fit the Kalman Filter model to the simulated processes and estimate beta(t) and Yest(t). Hence produce estimates kfalpha(t) = Yobs(t) – Yest(t) and compare these with the known, true alpha(t).

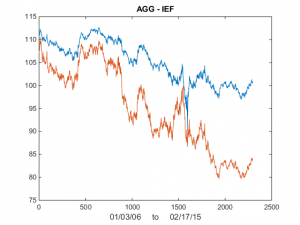

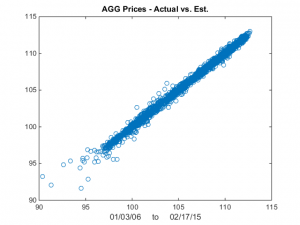

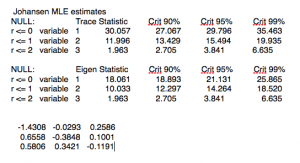

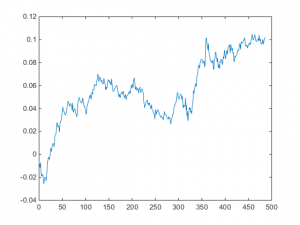

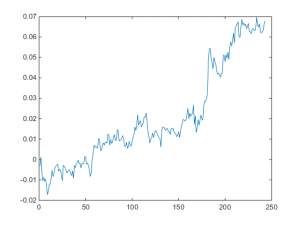

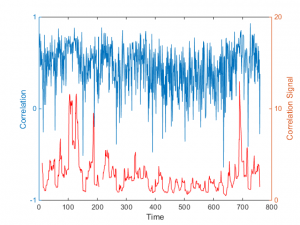

The charts in Fig. 1 below illustrate the procedure for a stock process X(t) with annual drift of 10%, annual volatility 40%, beta process variance Q of 8.65E-9 and price process variance R of 5.62E-2 (Q/R ratio of 1.54E-7).

Fig. 1 True and Estimated Beta and Alpha Using the Kalman Filter

As you can see, the Kalman Filter does a very good job of updating its beta estimate to track the underlying, true beta (which, in this experiment, is known). As the noise ratio Q/R is small, the Kalman Filter estimates of the process alpha, kfalpha(t), correspond closely to the true alpha(t), which again are known to us in this experimental setting. You can examine the relationship between the true alpha(t) and the Kalman Filter estimates kfalpha(t) is the chart in the upmost left quadrant of the figure. The correlation between the two is around 89%. With a level of accuracy this good for our alpha estimates, the pair of simulated stocks would make an ideal candidate for a pairs trading strategy.

Of course, the outcome is highly dependent on the values we assume for Q and R (and also to some degree on the assumptions made about the drift and volatility of the price process X(t)).

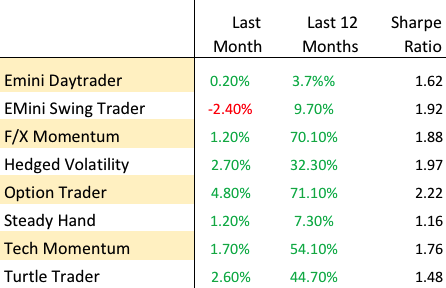

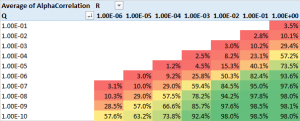

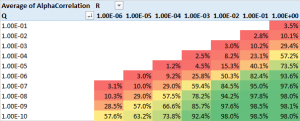

The next stage of the analysis is therefore to generate a large number of simulated price and beta observations and examine the impact of different levels of Q and R, the variances of the beta and price process. The results are summarized in the table in Fig 2 below.

Fig 2. Correlation between true alpha(t) and kfalpha(t) for values of Q and R

As anticipated, the correlation between the true alpha(t) and the estimates produced by the Kalman Filter is very high when the signal:noise ratio is small, i.e. of the order of 1E-6, or less. Average correlations begin to tail off very quickly when Q/R exceeds this level, falling to as low as 30% when the noise ratio exceeds 1E-3. With a Q/R ratio of 1E-2 or higher, the alpha estimates become too noisy to be useful.

I find it rather fortuitous, even implausible, that in their study Rudy, et al, feel able to assume a noise ratio of 3E-7 for all of the stock pairs in their study, which just happens to be in the sweet spot for alpha estimation. From my own research, a much larger value in the region of 1E-3 to 1E-5 is more typical. Furthermore, the noise ratio varies significantly from pair to pair, and over time. Indeed, I would go so far as to recommend applying a noise ratio filter to the strategy, meaning that trading signals are ignored when the noise ratio exceeds some specified level.

The take-away is this: the Kalman Filter approach can be applied very successfully in developing statistical arbitrage strategies, but only for processes where the noise ratio is not too large. One suggestion is to use a filter rule to supress trade signals generated at times when the noise ratio is too large, and/or to increase allocations to pairs in which the noise ratio is relatively low.